Precursors

Roman law

Roman law was codified, and in the south of France the Jus gentium continued to be used, although mostly only in the case of public and administrative law, and private law was left to the localities to determine. [4]

The distinction between private law and public law goes back to Ulpian, a Roman jurist of the third century, [5] who wrote: "Public law is what regards the welfare of the Roman state, private law what regards the interests of individual persons; because some things are of public, others of private utility." [6] [lower-alpha 2]Old French law

The sixth century Lex Romana Visigothorum was the most important document reflecting this usage. But classic Roman law became vulgarized through mixture with local laws, and under the influence of victorious Germanic Frankish tribes, who had their own, customary law, which became written around the sixth century, such as the Lex Salica and the Lex Ripuaria. With a multiplicity of laws, which one was applied became aligned with the dominant race in an area. A demarcation line roughly along the Loire River evolved, where south of the Loire the law depended on a version of customary Roman law and was known as the "land of written law" (le pays de droit écrit), whereas north of the Loire, it depended more on laws of Germanic origin and was known as the "land of customary law" (le pays de droit coutumier), which was still influenced by Roman law to fill in missing portions. [7] [8]

In the 12th century and after, there was renewed interest in Roman law throughout France. In the north, local customary laws began to be consolidated and written, under a decree by Charles VII in 1454 (Ordinance of Montils-les-Tours [ fr ]), [9] [10] and became an important source of written law which influenced the Napoleonic code. [10] Beyond just forming the base of written customary law, it also gained enough authority to inspire written commentary on it, which in the aggregate came to be recognized as a body of general principles of French customary law, despite some regional differences. [10] [lower-alpha 3] But it wasn't until the 17th century that many of them were written, such as Customary law in Burgundy [ fr ], in Paris, Brittany [ fr ], and other French customary laws [ fr ]. The difference between (droit écrit and droit coutumier) lasted until 1789. [9] [12]

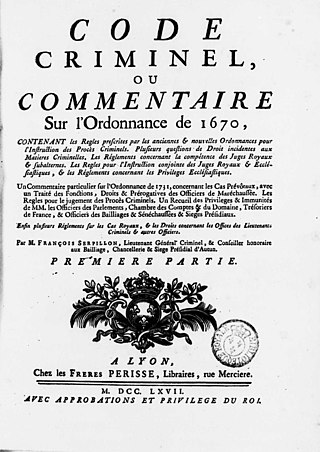

1670 code

The idea of codification of law goes back to antiquity. [lower-alpha 4] The Ancien regime had no penal code; however, it had a code of criminal procedure in the form of the Criminal Ordinance of 1670 (ordonnance criminelle de 1670). [13] It remained in force until the French Revolution, when it was repealed by a decree adopted by the National Constituent Assembly on 9 October 1789.

1808 code

The Code of Criminal Procedure (Code d'instruction criminelle) is a collection of legal texts which organized criminal procedure in the revolutionary era in France. Envisaged as early as 1801, it was promulgated on 16 November 1808.

The code established the Cour d'assises to try crimes (major felonies). There was one court in each department, and were the only courts in France to use juries [ fr ], which were composed of twelve jurors. The court initially had a chief justice (président) and four other justices (two others after 1831) who voted with the président to determine the sentence. Trial proceedings in the cour d'assises were theatrical in nature, with the président, the jurors, the court clerk, the public prosecutor, witnesses, and the defendant all taking part in more or less formalized declarations at different points of the trial, which could go on for several days. It concluded with the prosecution offering its closing argument, followed by the defense. Flashes of oratorical style might be used to influence impressionable jurors. Before 1881, the chief justice might present a summation, which could neutralize somewhat the dramatic final arguments. Jurors rendered their verdict based on impressions, and a majority (seven of twelve) was sufficient to convict. [14]

The 1808 code made legal assistance obligatory for a criminal defendant, and if he could not choose one, the judge assigned him one on the spot, under penalty of nullifying the entire procedure that follows. [15] [lower-alpha 5]

The 1808 code was repealed with the advent of the Fifth Republic, and replaced by the Code of criminal procedure of 1958.