Related Research Articles

Antioxidants are compounds that inhibit oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce free radicals. Autoxidation leads to degradation of organic compounds, including living matter. Antioxidants are frequently added to industrial products, such as polymers, fuels, and lubricants, to extend their usable lifetimes. Food are also treated with antioxidants to forestall spoilage, in particular the rancidification of oils and fats. In cells, antioxidants such as glutathione, mycothiol or bacillithiol, and enzyme systems like superoxide dismutase, can prevent damage from oxidative stress.

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight, and constitutes about 10% of the total electromagnetic radiation output from the Sun. It is also produced by electric arcs; Cherenkov radiation; and specialized lights; such as mercury-vapor lamps, tanning lamps, and black lights. Although long-wavelength ultraviolet is not considered an ionizing radiation because its photons lack the energy to ionize atoms, it can cause chemical reactions and causes many substances to glow or fluoresce. Many practical applications, including chemical and biological effects, derive from the way that UV radiation can interact with organic molecules. These interactions can involve absorption or adjusting energy states in molecules, but do not necessarily involve heating.

Cyanobacteria, also called Cyanobacteriota or Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name cyanobacteria refers to their color, which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blue-green algae, although they are not usually scientifically classified as algae. They appear to have originated in a freshwater or terrestrial environment. Sericytochromatia, the proposed name of the paraphyletic and most basal group, is the ancestor of both the non-photosynthetic group Melainabacteria and the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, also called Oxyphotobacteria.

Sunscreen, also known as sunblock or sun cream, is a photoprotective topical product for the skin that helps protect against sunburn and most importantly prevent skin cancer. Sunscreens come as lotions, sprays, gels, foams, sticks, powders and other topical products. Sunscreens are common supplements to clothing, particularly sunglasses, sunhats and special sun protective clothing, and other forms of photoprotection.

Sunless tanning, also known as UV filled tanning, self tanning, spray tanning, or fake tanning, refers to the effect of a suntan without exposure to the Sun. Sunless tanning involves the use of oral agents (carotenids), or creams, lotions or sprays applied to the skin. Skin-applied products may be skin-reactive agents or temporary bronzers (colorants).

Phycocyanin is a pigment-protein complex from the light-harvesting phycobiliprotein family, along with allophycocyanin and phycoerythrin. It is an accessory pigment to chlorophyll. All phycobiliproteins are water-soluble, so they cannot exist within the membrane like carotenoids can. Instead, phycobiliproteins aggregate to form clusters that adhere to the membrane called phycobilisomes. Phycocyanin is a characteristic light blue color, absorbing orange and red light, particularly near 620 nm, and emits fluorescence at about 650 nm. Allophycocyanin absorbs and emits at longer wavelengths than phycocyanin C or phycocyanin R. Phycocyanins are found in cyanobacteria. Phycobiliproteins have fluorescent properties that are used in immunoassay kits. Phycocyanin is from the Greek phyco meaning “algae” and cyanin is from the English word “cyan", which conventionally means a shade of blue-green and is derived from the Greek “kyanos" which means a somewhat different color: "dark blue". The product phycocyanin, produced by Aphanizomenon flos-aquae and Spirulina, is for example used in the food and beverage industry as the natural coloring agent 'Lina Blue' or 'EXBERRY Shade Blue' and is found in sweets and ice cream. In addition, fluorescence detection of phycocyanin pigments in water samples is a useful method to monitor cyanobacteria biomass.

The aggregating anemone, or clonal anemone, is the most abundant species of sea anemone found on rocky, tide swept shores along the Pacific coast of North America. This cnidarian hosts endosymbiotic algae called zooxanthellae that contribute substantially to primary productivity in the intertidal zone. The aggregating anemone has become a model organism for the study of temperate cnidarian-algal symbioses.

Avobenzone is an organic molecule and an oil-soluble ingredient used in sunscreen products to absorb the full spectrum of UVA rays.

UV filters are compounds, mixtures, or materials that block or absorb ultraviolet (UV) light. One of the major applications of UV filters is their use as sunscreens to protect skin from sunburn and other sun/UV related damage. After the invention of digital cameras changed the field of photography, UV filters have been used to coat glass discs fitted to camera lenses to protect hardware that is sensitive to UV light.

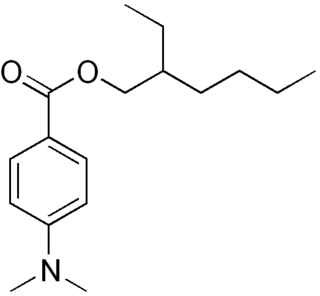

Padimate O is an organic compound related to the water-soluble compound PABA that is used as an ingredient in some sunscreens. This yellowish water-insoluble oily liquid is an ester formed by the condensation of 2-ethylhexanol with dimethylaminobenzoic acid. Other names for padimate O include 2-ethylhexyl 4-dimethylaminobenzoate, Escalol 507, octyldimethyl PABA, and OD-PABA.

Photoprotection is the biochemical process that helps organisms cope with molecular damage caused by sunlight. Plants and other oxygenic phototrophs have developed a suite of photoprotective mechanisms to prevent photoinhibition and oxidative stress caused by excess or fluctuating light conditions. Humans and other animals have also developed photoprotective mechanisms to avoid UV photodamage to the skin, prevent DNA damage, and minimize the downstream effects of oxidative stress.

Biological pigments, also known simply as pigments or biochromes, are substances produced by living organisms that have a color resulting from selective color absorption. Biological pigments include plant pigments and flower pigments. Many biological structures, such as skin, eyes, feathers, fur and hair contain pigments such as melanin in specialized cells called chromatophores. In some species, pigments accrue over very long periods during an individual's lifespan.

Pyrimidine dimers are molecular lesions formed from thymine or cytosine bases in DNA via photochemical reactions, commonly associated with direct DNA damage. Ultraviolet light induces the formation of covalent linkages between consecutive bases along the nucleotide chain in the vicinity of their carbon–carbon double bonds. The photo-coupled dimers are fluorescent. The dimerization reaction can also occur among pyrimidine bases in dsRNA —uracil or cytosine. Two common UV products are cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6–4 photoproducts. These premutagenic lesions alter the structure of the DNA helix and cause non-canonical base pairing. Specifically, adjacent thymines or cytosines in DNA will form a cyclobutane ring when joined together and cause a distortion in the DNA. This distortion prevents replication or transcription machinery beyond the site of the dimerization. Up to 50–100 such reactions per second might occur in a skin cell during exposure to sunlight, but are usually corrected within seconds by photolyase reactivation or nucleotide excision repair. In humans, the most common form of DNA repair is nucleotide excision repair (NER). In contrast, organisms such as bacteria can counterintuitively harvest energy from the sun to fix DNA damage from pyrimidine dimers via photolyase activity. If these lesions are not fixed, polymerase machinery may misread or add in the incorrect nucleotide to the strand. If the damage to the DNA is overwhelming, mutations can arise within the genome of an organism and may lead to the production of cancer cells. Uncorrected lesions can inhibit polymerases, cause misreading during transcription or replication, or lead to arrest of replication. It causes sunburn and it triggers the production of melanin. Pyrimidine dimers are the primary cause of melanomas in humans.

An aromatic amino acid is an amino acid that includes an aromatic ring.

EXPOSE is a multi-user facility mounted outside the International Space Station (ISS) dedicated to astrobiology. EXPOSE was developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) for long-term spaceflights and was designed to allow exposure of chemical and biological samples to outer space while recording data during exposure.

Cyanobionts are cyanobacteria that live in symbiosis with a wide range of organisms such as terrestrial or aquatic plants; as well as, algal and fungal species. They can reside within extracellular or intracellular structures of the host. In order for a cyanobacterium to successfully form a symbiotic relationship, it must be able to exchange signals with the host, overcome defense mounted by the host, be capable of hormogonia formation, chemotaxis, heterocyst formation, as well as possess adequate resilience to reside in host tissue which may present extreme conditions, such as low oxygen levels, and/or acidic mucilage. The most well-known plant-associated cyanobionts belong to the genus Nostoc. With the ability to differentiate into several cell types that have various functions, members of the genus Nostoc have the morphological plasticity, flexibility and adaptability to adjust to a wide range of environmental conditions, contributing to its high capacity to form symbiotic relationships with other organisms. Several cyanobionts involved with fungi and marine organisms also belong to the genera Richelia, Calothrix, Synechocystis, Aphanocapsa and Anabaena, as well as the species Oscillatoria spongeliae. Although there are many documented symbioses between cyanobacteria and marine organisms, little is known about the nature of many of these symbioses. The possibility of discovering more novel symbiotic relationships is apparent from preliminary microscopic observations.

Chroococcidiopsis is a photosynthetic, coccoidal bacterium. A diversity of species and cultures exist within the genus, with a diversity of phenotypes. Some extremophile members of the order Chroococidiopsidales are known for their ability to survive harsh environmental conditions, including both high and low temperatures, ionizing radiation, and high salinity.

Scytonemin is a secondary metabolite and an extracellular matrix (sheath) pigment synthesized by many strains of cyanobacteria, including Nostoc, Scytonema, Calothrix, Lyngbya, Rivularia, Chlorogloeopsis, and Hyella. Scytonemin-synthesizing cyanobacteria often inhabit highly insolated terrestrial, freshwater and coastal environments such as deserts, semideserts, rocks, cliffs, marine intertidal flats, and hot springs.

Exobiology Radiation Assembly (ERA) was an experiment that investigated the biological effects of space radiation. An astrobiology mission developed by the European Space Agency (ESA), it took place aboard the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA), an unmanned 4.5 tonne satellite with a payload of 15 experiments.

The slime coat is the coating of mucus covering the body of all fish. An important part of fish anatomy, it serves many functions, depending on species, ranging from locomotion, care and feeding of offspring, to resistance to disease and parasites.

References

- ↑ Cardozo KH, Guaratini T, Barros MP, Falcão VR, Tonon AP, Lopes NP, Campos S, Torres MA, Souza AO, Colepicolo P, Pinto E (2007). "Metabolites from algae with economical impact". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Toxicology & Pharmacology. 146 (1–2): 60–78. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.05.007. PMID 16901759.

- ↑ Wada N, Sakamoto T, Matsugo S (September 2015). "Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids and Their Derivatives as Natural Antioxidants". Antioxidants. 4 (3): 603–46. doi: 10.3390/antiox4030603 . PMC 4665425 . PMID 26783847.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oren A, Gunde-Cimerman N (April 2007). "Mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids: UV protectants or multipurpose secondary metabolites?". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 269 (1): 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00650.x . PMID 17286572.

- ↑ Sen, Sutrishna; Mallick, Nirupama (2021-10-01). "Mycosporine-like amino acids: Algal metabolites shaping the safety and sustainability profiles of commercial sunscreens". Algal Research. 58: 102425. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2021.102425. ISSN 2211-9264.

- ↑ Arai T, Nishijima M, Adachi K, Sano H (1992). "Isolation and structure of a UV absorbing substance from the marine bacterium Micrococcus sp". MBI Report.

- 1 2 Garcia-Pichel F, Castenholz RW (1993). "Occurrence of UV-Absorbing, Mycosporine-Like Compounds among Cyanobacterial Isolates and an Estimate of Their Screening Capacity". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 59 (1): 163–9. Bibcode:1993ApEnM..59..163G. doi:10.1128/AEM.59.1.163-169.1993. PMC 202072 . PMID 16348839.

- ↑ Okaichi T, Tokumura T. Isolation of cyclohexene derivatives from Noctiluca miliaris. 1980 Chemical Society of Japan

- 1 2 Kogej T, Gostinčar C, Volkmann M, Gorbushina AA, Gunde-Cimerman N (2006). "Mycosporines in Extremophilic Fungi—Novel Complementary Osmolytes?". Environmental Chemistry. 3 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1071/En06012. S2CID 53453659.

- ↑ Libkind D, Moliné M, Sommaruga R, Sampaio JP, van Broock M (August 2011). "Phylogenetic distribution of fungal mycosporines within the Pucciniomycotina (Basidiomycota)". Yeast. 28 (8): 619–27. doi:10.1002/yea.1891. PMID 21744380. S2CID 25297465.

- 1 2 Rezanka T, Temina M, Tolstikov AG, Dembitsky VM (2004). "Natural Microbial UV Radiation Filters – Mycosporine-like Amino Acids". Folia Microbiologica. 49 (4): 339–352. doi:10.1007/bf03354663. PMID 15530001. S2CID 35045772.

- ↑ Garcia-Pichel F, Wingard CE, Castenholz RW (1993). "Evidence Regarding the UV Sunscreen Role of a Mycosporine-Like Compound in the Cyanobacterium Gloeocapsa sp". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 59 (1): 170–6. Bibcode:1993ApEnM..59..170G. doi:10.1128/AEM.59.1.170-176.1993. PMC 202073 . PMID 16348840.

- ↑ Korbee N, Figueroa FL, Aguilera J (March 2006). "Acumulación de aminoácidos tipo micosporina (MAAs): biosíntesis, fotocontrol y funciones ecofisiológicas". Revista chilena de historia natural. 79 (1): 119–132. doi: 10.4067/S0716-078X2006000100010 . ISSN 0716-078X.

- ↑ Bandaranayake WM. 1998. Mycosporines: are they nature’s sunscreens? Natural Product Reports. 159–171.

- ↑ Carreto JI, Carignan MO (March 2011). "Mycosporine-like amino acids: relevant secondary metabolites. Chemical and ecological aspects". Marine Drugs. 9 (3): 387–446. doi: 10.3390/md9030387 . PMC 3083659 . PMID 21556168.

- ↑ D'Agostino PM, Javalkote VS, Mazmouz R, Pickford R, Puranik PR, Neilan BA (October 2016). "Comparative Profiling and Discovery of Novel Glycosylated Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids in Two Strains of the Cyanobacterium Scytonema cf. crispum". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 82 (19): 5951–9. Bibcode:2016ApEnM..82.5951D. doi:10.1128/AEM.01633-16. PMC 5038028 . PMID 27474710.

- 1 2 Pope MA, Spence E, Seralvo V, Gacesa R, Heidelberger S, Weston AJ, Dunlap WC, Shick JM, Long PF (January 2015). "O-Methyltransferase is shared between the pentose phosphate and shikimate pathways and is essential for mycosporine-like amino acid biosynthesis in Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413". ChemBioChem. 16 (2): 320–7. doi:10.1002/cbic.201402516. PMID 25487723. S2CID 32715519.

- ↑ Singh SP, Kumari S, Rastogi RP, Singh KL, Sinha RP (2008). "Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs): chemical structure, biosynthesis and significance as UV-absorbing/screening compounds" (PDF). Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 46 (1): 7–17. PMID 18697565.

- ↑ Libkind D, Pérez P, Sommaruga R, Diéguez Mdel C, Ferraro M, Brizzio S, Zagarese H, van Broock M (March 2004). "Constitutive and UV-inducible synthesis of photoprotective compounds (carotenoids and mycosporines) by freshwater yeasts". Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 3 (3): 281–6. doi:10.1039/b310608j. PMID 14993945. S2CID 9172968.

- ↑ Portwich A, Garcia-Pichel F (1999). "Ultraviolet and osmotic stresses induce and regulate the synthesis of mycosporines in the cyanobacterium chlorogloeopsis PCC 6912". Archives of Microbiology. 172 (4): 187–92. doi:10.1007/s002030050759. PMID 10525734. S2CID 1717569.

- ↑ Neale PJ, Banaszak AT, Jarriel CR (1998). "Ultraviolet sunscreens in Gymnodinium sanguineum (Dinophyceae): mycosporine-like amino acids protect against inhibition of photosynthesis". J Phycol. 34 (6): 928–938. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340928.x. S2CID 59057431.

- ↑ Sun, Yingying; Zhang, Naisheng; Zhou, Jing; Dong, Shasha; Zhang, Xin; Guo, Lei; Guo, Ganlin (January 2020). "Distribution, Contents, and Types of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs) in Marine Macroalgae and a Database for MAAs Based on These Characteristics". Marine Drugs. 18 (1): 43. doi: 10.3390/md18010043 . PMC 7024296 . PMID 31936139.

- ↑ Sampedro D (April 2011). "Computational exploration of natural sunscreens". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 13 (13): 5584–6. Bibcode:2011PCCP...13.5584S. doi:10.1039/C0CP02901G. PMID 21350786. S2CID 37802091.

- ↑ Koizumi K, Hatakeyama M, Boero M, Nobusada K, Hori H, Misonou T, Nakamura S (June 2017). "How seaweeds release the excess energy from sunlight to surrounding sea water" (PDF). Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 19 (24): 15745–15753. Bibcode:2017PCCP...1915745K. doi:10.1039/C7CP02699D. PMID 28604867.

- ↑ Portwich A, Garcia-Pichel F (2000). "A novel prokaryotic UVB photoreceptor in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis PCC 6912". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 71 (4): 493–8. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2000)0710493anpupi2.0.co2. PMID 10824604. S2CID 222100865.

- ↑ Lawrence KP, Gacesa R, Long PF, Young AR (November 2017). "Molecular photoprotection of human keratinocytes in vitro by the naturally occurring mycosporine-like amino acid (MAA) palythine". The British Journal of Dermatology. 178 (6): 1353–1363. doi:10.1111/bjd.16125. PMC 6032870 . PMID 29131317.

- ↑ Yakovleva I, Bhagooli R, Takemura A, Hidaka M (2004). "Differential susceptibility to oxidative stress of two scleractinian corals: antioxidant functioning of mycosporine-glycine". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 139 (4): 721–30. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.08.016. PMID 15581804.

- ↑ Suh HJ, Lee HW, Jung J (2003). "Mycosporine glycine protects biological systems against photodynamic damage by quenching singlet oxygen with a high efficiency". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 78 (2): 109–13. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2003)0780109mgpbsa2.0.co2. PMID 12945577. S2CID 20491255.

- ↑ Dunlap WC, Yamamoto Y (September 1995). "Small-molecule antioxidants in marine organisms: Antioxidant activity of mycosporine-glycine". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 112 (1): 105–114. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(95)00086-N.

- ↑ Canfield DE, Sorensen KB, Oren A (July 2004). "Biogeochemistry of a gypsum-encrusted microbial ecosystem". Geobiology. 2 (3): 133–150. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4677.2004.00029.x. S2CID 129724758.

- ↑ Sivalingam PM, Ikawa T, Nisizawa K (1976). "Physiological Roles of a Substance 334 in Algae". Botanica Marina. 19 (1). doi:10.1515/botm.1976.19.1.9. S2CID 84819485.

- ↑ Bhandari R, Sharma PK (2007). "Effect of UV-B and high visual radiation on photosynthesis in freshwater (nostoc spongiaeforme) and marine (Phormidium corium) cyanobacteria". Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 44 (4): 231–9. PMID 17970281.

- ↑ "With 'biological sunscreen,' mantis shrimp see the reef in a whole different light". 3 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ↑ Bok MJ, Porter ML, Place AR, Cronin TW (July 2014). "Biological sunscreens tune polychromatic ultraviolet vision in mantis shrimp". Current Biology. 24 (14): 1636–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.071 . PMID 24998530.

- ↑ Oren A (July 1997). "Mycosporine‐like amino acids as osmotic solutes in a community of halophilic cyanobacteria". Geomicrobiology Journal. 14 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1080/01490459709378046.

- ↑ Wright DJ, Smith SC, Joardar V, Scherer S, Jervis J, Warren A, Helm RF, Potts M (December 2005). "UV irradiation and desiccation modulate the three-dimensional extracellular matrix of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (48): 40271–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m505961200 . PMID 16192267.

- ↑ Tirkey J, Adhikary S (2005). "Cyanobacteria in biological soil crusts of india". Current Science. 89 (3): 515–521.

- ↑ Michalek-Wagner K, Willis B (2001). "Impacts of bleaching on the soft coral lobophytum compactum. ii. biochemical changes in adults and their eggs". Coral Reefs. 19 (3): 240–246. doi:10.1007/pl00006959. S2CID 123582.

- ↑ Dunlap WC, Shick JM (1998). "Ultraviolet radiation-absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids in coral reef organisms: a biochemical and environmental perspective". J Phycol. 34: 418–430. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340418.x. S2CID 5988147.