Halakha, also transliterated as halacha, halakhah, and halocho, is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandments (mitzvot), subsequent Talmudic and rabbinic laws, and the customs and traditions which were compiled in the many books such as the Shulchan Aruch. Halakha is often translated as "Jewish law", although a more literal translation might be "the way to behave" or "the way of walking". The word is derived from the root which means "to behave". Halakha not only guides religious practices and beliefs; it also guides numerous aspects of day-to-day life.

A rabbi is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as semikha—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of the rabbi developed in the Pharisaic and Talmudic eras, when learned teachers assembled to codify Judaism's written and oral laws. The title "rabbi" was first used in the first century CE. In more recent centuries, the duties of a rabbi became increasingly influenced by the duties of the Protestant Christian minister, hence the title "pulpit rabbis", and in 19th-century Germany and the United States rabbinic activities including sermons, pastoral counseling, and representing the community to the outside, all increased in importance.

Modern Orthodox Judaism is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that attempts to synthesize Jewish values and the observance of Jewish law with the modern world.

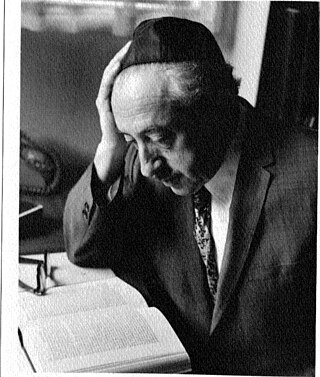

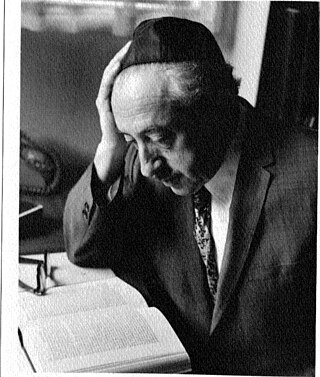

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik was a major American Orthodox rabbi, Talmudist, and modern Jewish philosopher. He was a scion of the Lithuanian Jewish Soloveitchik rabbinic dynasty.

Akiva ben Joseph, also known as Rabbi Akiva, was a leading Jewish scholar and sage, a tanna of the latter part of the first century and the beginning of the second. Rabbi Akiva was a leading contributor to the Mishnah and to Midrash halakha. He is referred to in Tosafot as Rosh la-Hakhamim. He was executed by the Romans in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba revolt. He has also been described as a philosopher.

Semikhah is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

Ovadia Yosef was an Iraqi-born Talmudic scholar, a posek, the Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel from 1973 to 1983, and a founder and long-time spiritual leader of Israel's ultra-Orthodox Shas party. Yosef's responsa were highly regarded within Haredi circles, particularly among Mizrahi communities, among whom he was regarded as "the most important living halakhic authority".

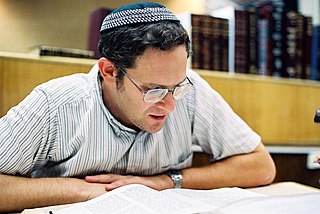

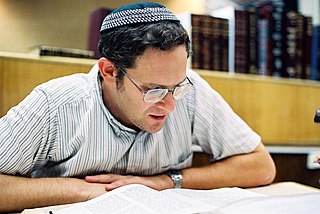

Religious Zionism is a religious denomination that views Zionism as a fundamental component of Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as Dati Leumi, and in Israel, they are most commonly known by the plural form of the first part of that term: Datiim. The community is sometimes called 'Knitted kippah', the typical head covering worn by male adherents to Religious Zionism.

Shlomo Riskin is an Orthodox rabbi, and the founding rabbi of Lincoln Square Synagogue on the Upper West Side of New York City, which he led for 20 years; founding chief rabbi of the Israeli settlement of Efrat in the Israeli-occupied West Bank; former dean of Manhattan Day School in New York City; and founder and Chancellor of the Ohr Torah Stone Institutions, a network of high schools, colleges, and graduate Programs in the United States and Israel.

"Who is a Jew?", is a basic question about Jewish identity and considerations of Jewish self-identification. The question pertains to ideas about Jewish personhood, which have cultural, ethnic, religious, political, genealogical, and personal dimensions. Orthodox Judaism and Conservative Judaism follow Jewish law (halakha), deeming people to be Jewish if their mothers are Jewish or if they underwent a halakhic conversion. Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism accept both matrilineal and patrilineal descent as well as conversion. Karaite Judaism predominantly follows patrilineal descent as well as conversion.

Torah Umadda is a worldview in Orthodox Judaism concerning the relationship between the secular world and Judaism, and in particular between secular knowledge and Jewish religious knowledge. The resultant mode of Orthodox Judaism is referred to as Centrist Orthodoxy.

Rabbinic authority in Judaism relates to the theological and communal authority attributed to rabbis and their pronouncements in matters of Jewish law. The extent of rabbinic authority differs by various Jewish groups and denominations throughout history.

Eliezer Berkovits was a rabbi, theologian, and educator in the tradition of Orthodox Judaism.

Shlomo Goren, was a Polish-born Israeli rabbi and Talmudic scholar. An Orthodox Jew and Religious Zionist, he was considered a foremost rabbinical legal authority on matters of Jewish religious law (halakha). In 1948, Goren founded and served as the first head of the Military Rabbinate of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), a position he held until 1968. Subsequently, he served as Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv–Jaffa between 1968 and his 1972 election as the Chief Rabbi of Israel; the fourth Ashkenazi Jew to hold office. After his 1983 retirement from the country's Chief Rabbinate, Goren served as the head of a yeshiva that he established in Jerusalem.

Jewish feminism is a movement that seeks to make the religious, legal, and social status of Jewish women equal to that of Jewish men in Judaism. Feminist movements, with varying approaches and successes, have opened up within all major branches of the Jewish religion.

Yitzhak Yosef is an Israeli Haredi rabbi. The former Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel, he also serves as the rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Hazon Ovadia in Jerusalem's Romema neighborhood. Since the end of his term as Chief Rabbi, he joined the rabbinic leadership council of the Shas party.

Yakov Meir Nagen is an Israeli rabbi and author. Nagen is a leader in interfaith dialogue and in particular interfaith peace initiatives between Judaism and Islam. He is the Director of the Blickle Institute for Interfaith Dialogue and the Beit Midrash for Judaism and Humanity. Nagen also teaches at Yeshivat Otniel and has written extensively about Jewish philosophy and Talmud.

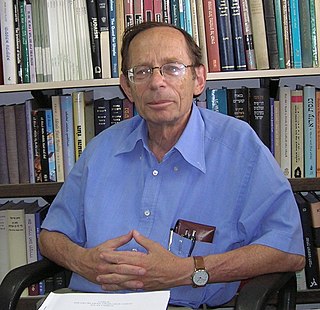

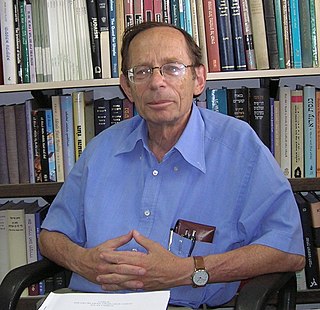

Gerald Blidstein was professor emeritus of Jewish philosophy at Israel's Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He was the Israel Prize laureate in Jewish philosophy (2006) and had been a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences since 2007.

Rabbi David Stav is the chief rabbi of the city of Shoham, the chairman of the Tzohar organization, and serves as a rabbi for the Ezra youth movement.

Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah is a nonprofit organization in Israel that focuses on education research and policy in the Religious Zionist community. The organization supports democratizing the State-controlled religious services, so that the public plays a greater role in religious decision making and functions.