Degenerate art was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, was removed from state-owned museums and banned in Nazi Germany on the grounds that such art was an "insult to German feeling", un-German, Freemasonic, Jewish, or Communist in nature. Those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions that included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce art.

Rhineland bastard was a derogatory term used in Nazi Germany to describe Afro-Germans, born of mixed-race relationships between German women and black African men of the French Army who were stationed in the Rhineland during its occupation by France after World War I.

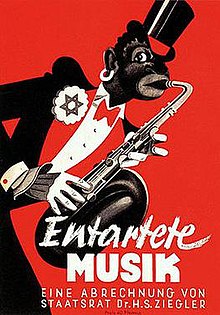

Degenerate music was a label applied in the 1930s by the government of Nazi Germany to certain forms of music that it considered harmful or decadent. The Nazi government's concerns about degenerate music were a part of its larger and better-known campaign against degenerate art. In both cases, the government attempted to isolate, discredit, discourage, or ban the works.

The Swing Youth were a youth counterculture of jazz and swing lovers in Germany formed in Hamburg in 1939. Primarily active in Hamburg and Berlin, they were composed of 14- to 21-year-old Germans, mostly middle or upper-class students, but also including some in the working class. They admired the "American way of life", defining themselves in swing music and opposing Nazism, especially the Hitler Youth. They loosely structured themselves into “clubs” with names such as the Harlem Club, the OK Gang, and the Hot Club. This underground subculture, distinctly nonconformist with a focus on African-American music, was active in the German youth scene. Despite being largely apolitical and unstructured, the Swing Youth were targeted and, in some cases, repressed by the Nazi government.

Adolf Ziegler was a German painter and politician. He was tasked by the Nazi Party to oversee the purging of what the Party described as "degenerate art", by most of the German modern artists. He was Hitler's favourite painter. He was born in Bremen and died in Varnhalt, today Baden-Baden.

The Nazi regime in Germany actively promoted and censored forms of art between 1933 and 1945. Upon becoming dictator in 1933, Adolf Hitler gave his personal artistic preference the force of law to a degree rarely known before. In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, seen by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal. It was, furthermore, to be comprehensible to the average man. This art was to be both heroic and romantic. The Nazis viewed the culture of the Weimar period with disgust. Their response stemmed partly from conservative aesthetics and partly from their determination to use culture as propaganda.

Charlie and his Orchestra were a Nazi-sponsored German propaganda swing band. Jazz music styles were seen by Nazi authorities as rebellious but, ironically, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels conceived of using the style in shortwave radio broadcasts aimed initially at the United Kingdom, and later the United States, after the German declaration of war on 11 December 1941.

Friedrich Blume was professor of musicology at the University of Kiel from 1938 to 1958. He was a student in Munich, Berlin and Leipzig, and taught in the last two of these for some years before being called to the chair in Kiel. His early studies were on Lutheran church music, including several books on J.S. Bach, but broadened his interests considerably later. Among his prominent works were chief editor of the collected Praetorius edition, and he also edited the important Eulenburg scores of the major Mozart Piano Concertos. From 1949 he was involved in the planning and writing of Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart.

An overview of the evolution of Jazz music in Germany reveals that the development of jazz in Germany and its public notice differ from the "motherland" of jazz, the US, in several respects.

Feindsender was a term used in Nazi Germany to describe radio stations broadcasting from countries that were enemies of the German Reich before and during World War II, such as the United Kingdom or the United States. It also referred to radio stations in Germany which broadcast anti-Nazi material. The term has not been in general use since the downfall of the Third Reich.

Censorship in Nazi Germany was extreme and strictly enforced by the governing Nazi Party, but specifically by Joseph Goebbels and his Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Similarly to many other police states both before and since, censorship within Nazi Germany included the silencing of all past and present dissenting voices. In addition to the further propaganda weaponization of all forms of mass communication, including newspaper, music, literature, radio, and film, by the State, the Ministry of Propaganda also produced and disseminated their own literature, which was solely devoted to spreading Nazi ideology and the Hitler Myth.

Joseph Wulf was a German-Polish Jewish historian. A survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp, he was the author of several books about Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, including Das Dritte Reich und die Juden ; Heinrich Himmler (1960); and Martin Bormann: Hitlers Schatten (1962). The House of the Wannsee Conference museum in Berlin houses the Joseph Wulf Library in his honour.

The Reich Chamber of Music was a government agency which operated as a statutory corporation controlled by the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda that regulated the music industry in Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1945. It promoted "good German music" which was composed by Aryans and seen as consistent with Nazi ideals, while suppressing other, "degenerate" music, which included atonal music, jazz, and, especially, music by Jewish composers. The Chamber was founded in 1933 by Joseph Goebbels as part of the Reich Chamber of Culture, and it operated until the fall of the Nazi Germany in 1945.

American music during World War II was considered to be popular music that was enjoyed during the late 1930s through the mid-1940s.

The Reich Music Examination Office was an organisation within the Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda whose role was to prevent the distribution of 'undesirable' music within Nazi Germany. In doing so, it worked in conjunction with the Music Chamber of the Reich Chamber of Culture.

Music in Nazi Germany, like all cultural activities in the regime, was controlled and "co-ordinated" (Gleichschaltung) by various entities of the state and the Nazi Party, with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and the prominent Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg playing leading – and competing – roles. The primary concerns of these organizations was to exclude Jewish composers and musicians from publishing and performing music, and to prevent the public exhibition of music considered to be "Jewish", "anti-German", or otherwise "degenerate", while at the same time promoting the work of favored "Germanic" composers, such as Richard Wagner, Ludwig van Beethoven and Anton Bruckner. These works were believed to be positive contributions to the Volksgemeinschaft, or German folk community.

Hans Severus Ziegler was a German publicist, theater manager, teacher and Nazi Party official. A leading cultural director under the Nazis, he was closely associated with the censorship and cultural co-ordination of the Third Reich.

En Canot is a Cubist oil painting created by Jean Metzinger in 1913. The work is referred to in various publications as Femme à l'ombrelle, Im Boot, Le Canot, En Bâteau, In the Canoe, The Boat, On the Beach, Am Strand, Im Schiff, V Člunu and Im Kanu. The painting was exhibited in Paris at the 1913 Salon d'Automne. The following year it was shown at Moderní umění, 45th Exhibition of SVU Mánes in Prague, February–March 1914. This "Survey of Modern Art" was one of the last prewar exhibitions in Prague. En Canot was exhibited again, in July of the same year, at the Galerie Der Sturm, Berlin. The painting was acquired from Herwarth Walden in 1916 by Georg Muche at Galerie Der Sturm.

The Reich Music Days took place from 22 to 29 May 1938 in Düsseldorf. They were a Nazi propaganda event under the patronage of Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels had originally planned an annual return of the Reichsmusiktage. These were held again in May 1939, but ceased to exist after the beginning of the Second World War.

Fritz Stege was a German music journalist in the era of National Socialism and composer of accordion music.