Related Research Articles

Isaac Stern was an American violinist.

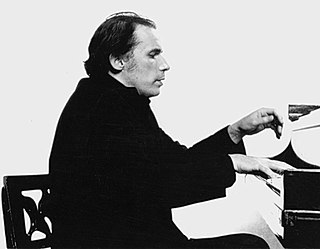

Glenn Herbert Gould was a Canadian classical pianist. He was among the most famous and celebrated pianists of the 20th century, renowned as an interpreter of the keyboard works of Johann Sebastian Bach. His playing was distinguished by remarkable technical proficiency and a capacity to articulate the contrapuntal texture of Bach's music.

The Columbia Symphony Orchestra was an orchestra formed by Columbia Records for the purpose of making recordings. In the 1950s, it provided a vehicle for some of Columbia's better known conductors and recording artists to record using only company resources. The musicians in the orchestra were contracted as needed for individual sessions and consisted of free-lance artists and often members of either the New York Philharmonic or the Los Angeles Philharmonic, depending on whether the recording was being made in Columbia's East Coast or West Coast studios.

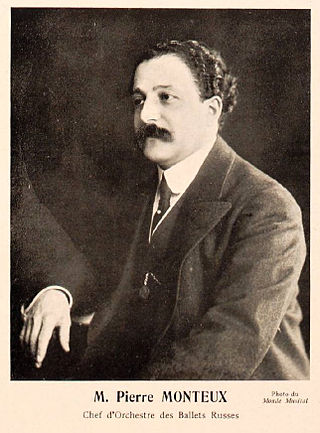

Pierre Benjamin Monteux was a French conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1907. He came to prominence when, for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company between 1911 and 1914, he conducted the world premieres of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring and other prominent works including Petrushka, The Nightingale, Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, and Debussy's Jeux. Thereafter he directed orchestras around the world for more than half a century.

Leopold Anthony Stokowski was a British-born American conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra. He was especially noted for his free-hand conducting style that spurned the traditional baton and for obtaining a characteristically sumptuous sound from the orchestras he directed.

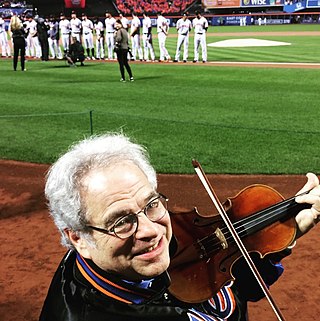

Itzhak Perlman is an Israeli-American violinist. He has performed worldwide and throughout the United States, in venues that have included a state dinner for Elizabeth II at the White House in 2007, and at the 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama. He has conducted the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Westchester Philharmonic. In 2015, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Perlman has won 16 Grammy Awards, including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and four Emmy Awards.

Julius Baker was one of the foremost American orchestral flute players. During the course of five decades he concertized with several of America's premier orchestral ensembles including the Chicago Symphony and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15, is a work for piano and orchestra completed by Johannes Brahms in 1858. The composer gave the work's public debut in Hanover, the following year. It was his first-performed orchestral work, and his first orchestral work performed to audience approval.

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American symphony orchestra based in Baltimore, Maryland. The Baltimore SO has its principal residence at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, where it performs more than 130 concerts a year. In 2005, it began regular performances at the Music Center at Strathmore in Bethesda.

Johann Baptist Isidor Richter, or János Richter was an Austro-Hungarian orchestral and operatic conductor.

Jaime Laredo is an American violinist and conductor. He was the conductor and music director of the Vermont Symphony Orchestra, and began his musical career when he was five years old.

João Carlos Gandra da Silva Martins ; born June 25, 1940) is a Brazilian classical pianist and conductor, who has performed with leading orchestras in the United States, Europe and Brazil.

The Zurich Chamber Orchestra is a Swiss chamber orchestra based in Zurich. The ZKO's principal concert venue in Zurich is the Tonhalle. The ZKO also performs in Zurich at the Schauspielhaus Zürich, the ZKO-Haus in the Seefeld quarter of the city, and such churches as the Fraumünster and the Kirche St. Peter.

Vladimir Golschmann was a French-American conductor.

Elisabeth Batiashvili, professionally known as Lisa Batiashvili, is a prominent Georgian violinist active across Europe and the United States. A former New York Philharmonic artist-in-residence, she is acclaimed for her "natural elegance, silky sound and the meticulous grace of her articulation". Batiashvili makes frequent appearances at high-profile international events; she was the violin soloist at the 2018 Nobel Prize concert.

James Zuill Bailey, better known as Zuill Bailey is an American Grammy Award-winning cello soloist, chamber musician, and artistic director. A graduate of the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University and the Juilliard School, he has appeared in recital and with major orchestras internationally. He is a professor of cello and Director of the Center for Entrepreneurship at the University of Texas at El Paso. Bailey’s extensive recording catalogue are released on TELARC, Avie, Steinway and Sons, Octave, Delos, Albany, Sono Luminus, Naxos, Azica, Concord, EuroArts, ASV, Oxingale and Zenph Studios.

Radu Lupu was a Romanian pianist. He was widely recognized as one of the greatest pianists of his time.

Ronald Turini is a world renowned Canadian classical pianist.

Jeffrey Alan Kahane is an American classical concert pianist and conductor. He was music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra for 20 years, the longest of any music director in the orchestra's history. He is the music director of the Sarasota Music Festival, a program of the Sarasota Orchestra, music director-designate of the San Antonio Philharmonic, and a professor of keyboard studies (Piano) at the USC Thornton School of Music in Los Angeles, California.

Eugen Indjic was a Yugoslav-born French-American pianist.

References

- ↑ "Who's the Boss?". The American Scholar. July 26, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- 1 2 Tim Page, in liner notes to the Sony release

- 1 2 3 Quoted by Schuyler Chapin in liner notes to the Sony release

- 1 2 3 Chapin

- ↑ Bazzana, Kevin (1997). Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work: A Study in Performance Practice. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 125. ISBN 0198166567.

- 1 2 3 John Canarina, in liner notes to the Sony release

- ↑ Transcription from "A Transcription of Leonard Bernstein's Introduction". F minor mailing list. Archived from the original on October 31, 2000. "Laughter" parentheticals and paragraph breaks incorporated from the transcription in Mesaros (2008), p. 251, in which details of wording are less accurate.

- ↑ Mesaros, Helen (2008). Bravo Fortissimo Glenn Gould. American Literary Press. p. 252.

- ↑ Bernstein, Leonard. "The Truth About a Legend". Leonard Bernstein Office. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ↑ Mesaros, Helen (March 2008). Bravo fortissimo Glenn Gould: the mind of a Canadian virtuoso. American Literary Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-56167-985-0 . Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ "Brahms Piano Concerto No 1". Gramophone. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ↑ Glenn Gould plays Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor (1-2) on YouTube; archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Symphony With Gould". The Baltimore Sun . October 10, 1962.

- ↑ Concert Hall Curveballs: Bernstein and Gould : NPR Music

- ↑ NPR's Performance Today

- ↑ Schickele, Peter. The Definitive Biography of P. D. Q. Bach . New York; Random House, 1976, p. 187.

- ↑ "6 avril 1962" (57 minutes), Radio Télévision Suisse, August 30, 2020 (in French)