Related Research Articles

The Mevlevi Order or Mawlawiyya is a Sufi order that originated in Konya and which was founded by the followers of Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet, Sufi mystic, and Islamic theologian. The Mevlevis are also known as the "whirling dervishes" due to their famous practice of whirling as a form of dhikr. Dervish is a common term for an initiate of the Sufi path; whirling is part of the formal sema ceremony and the participants are properly known as semazens.

Alī Imādud-Dīn Nasīmī, often known as Nesimi, was a 14th-century Azerbaijani Ḥurūfī poet. Known mostly by his pen name of Nasimi, he wrote in Azerbaijani, Persian and sometimes Arabic, being the composer of one divan in Azerbaijani, one in Persian, and a number of poems in Turkish and Arabic. He is considered one of the greatest Turkic mystical poets of the late 14th and early 15th centuries and one of the most prominent early divan masters in Turkic literary history. According to the third edition of the Encyclopedia of Islam Nasimi "is considered to be the true founder" of Turkic classicalʿarūḍ poetry.

Turkish literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in Turkic languages. The Ottoman and Azerbaijani forms of Turkish, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, were highly influenced by Persian and Arabic literature, and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet.

Azerbaijani literature is written in Azerbaijani, a Turkic language, which is the official state language of the Republic of Azerbaijan, where the North Azerbaijani variety is spoken. It is also natively spoken in Iran, where the South Azerbaijani variety is used, and is particularly spoken in the northwestern historic region of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani is also spoken natively in Russia, Georgia and Turkey. While the majority of Azerbaijani people live in Iran, modern Azerbaijani literature is overwhelmingly produced in the Republic of Azerbaijan, where the language has official status. Three scripts are used for writing the language: Azerbaijani Latin script in the Republic of Azerbaijan, Arabic script in Iran and Cyrillic script formerly used in Soviet Azerbaijan.

İsmet Özel is a Turkish poet and writer.

Mahammad bin Suleyman, better known by his pen name Fuzuli, was a 16th century poet, writer and thinker, who wrote in his native Azerbaijani, as well as Arabic and Persian languages. Considered one of the greatest contributors to the divan tradition of Azerbaijani literature, Fuzuli in fact wrote his collected poems (divan) in all three languages. He is also regarded as one of the greatest Ottoman lyrical poets with knowledge of both the Ottoman and Chagatai Turkic literary traditions, as well as mathematics and astronomy.

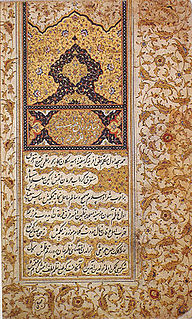

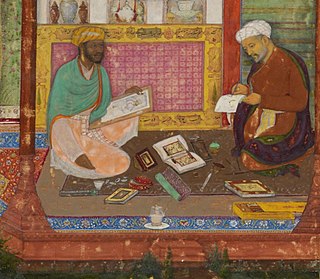

In Islamic cultures of the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily and South Asia, a Diwan is a collection of poems by one author, usually excluding his or her long poems (mathnawī). These poems, frequently sung or set to music, were often composed and collected in the imperial courts of various sultanates and were very well known for their ability to inspire. In modern-times, the inspirational, linguistic, verse, meter, and other design features of the Diwan or Masnavi poetry, are found echoing in other cultures, same or similar to the relaying of hidden messages, safety, and support, left for those ex-slaves on the Underground Railroad, during the American Civil War. Thus, themes that emerge from traditional Islamic origins can again portray of and evoke the persistence of life, or whatever continuances, admirable to the old or traditional ways and wisdoms. Where these are found in freeform variants, like an enigma, the modern Diwan, as powers brings a peculiar message encompassing for the divinities.

Ahmet Necip Fazıl Kısakürek was a Turkish poet, novelist, playwright, and Islamist ideologue. He is also known simply by his initials NFK. He was noticed by the French philosopher Henri Bergson, who later became his teacher.

Tevfik Kolaylı, better known by his pen name Neyzen Tevfik, was a Turkish poet, satirist, and neyzen. He was born in Bodrum and died in Istanbul. His name is occasionally misspelled as Neyzen Teyfik.

Hayâlî (خيالى) (1500?–1557) was the pen name of an Ottoman Turkish poet.

Ahmed Nedîm Efendi (نديم) (c. 1681 – 30 October 1730) was the pen name of one of the most celebrated Ottoman poets. He achieved his greatest fame during the reign of Ahmed III, the so-called Tulip Era from 1718 to 1730. He was known for his slightly decadent, even licentious poetry often couched in the most staid of classical formats, but also for bringing the folk poetic forms of türkü and şarkı into the court.

Ahmet Haşim was an influential Turkish poet of the early 20th century.

Mihri Hatun, also known as Lady Mihri and Mihri Khatun, was an Ottoman poet. She was the daughter of a kadi and according to sources she spent most of her life in and near Amasya, in Anatolia. Documentation places her as a member of the literary circle of Prince Ahmed, the son of Sultan Bayezid II.

Mehmed Orhan was the 42nd head of the Ottoman dynasty from 1983 to 1994. He was the advisor of King Zog I of Albania and succeeded as head of the Ottoman dynasty on 9 December 1983, following the death of Ali Vâsib.

Yahya Kemal Beyatlı, born Ahmet Âgâh, generally known by the pen name Yahya Kemal, was a leading Turkish poet and author, as well as a politician and diplomat.

Faruk Nafiz Çamlıbel was a leading Turkish poet, author and later politician.

Ataol Behramoğlu is a prominent Turkish poet, author, and Russian-into-Turkish literary translator.

Sabiha Sertel (1895–1968) was the first professional female journalist and publisher in modern Turkey. Her articles and columns advocated for reforming the rights of women and workers and criticized state oppression, imperialism, fascism and social inequalities in Turkey. Her high-profile activism for democracy, civil liberties and a free press resulted in social and political pressure, censorship, imprisonment and ultimately, exile. Sertel is considered the first to publicly marry outside the dönme community, Jews who converted to Islam in the 17th century but privately retained their beliefs and were viewed with suspicion by Muslims. She was the first Turkish woman to be tried in court and imprisoned for her writings. She also was one of the first Turkish women to die in political exile.

Yahya bey Dukagjini was an Ottoman poet and military figure. He is known for his Ottoman Turkish diwan poems of the 16th century.

Ayşe Hubbi Hatun was a lady-in-waiting to Sultan Selim II and later to his son Sultan Murad III of the Ottoman Empire. She was a notable female poet of the sixteenth century.

References

- ↑ Dede (n.d.)

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 252

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 297

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 133

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 252

- ↑ Şentürk (1999) , p. 555

- ↑ Cengiz (1983) , p. 535

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 147

- ↑ Cengiz (1983) , p. 544

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 131

- ↑ Berk (1999), p. 245

- ↑ Cengiz (1983) , p. 546

- ↑ Andrews, Black & Kalpaklı (2006) , p. 132

Bibliography

- Andrews, Walter G.; Black, Najaat; Kalpaklı, Mehmet (2006). Ottoman Lyric Poetry: an Anthology. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-295-98595-X.

- Berk, İlhan (1999). "Neşâtî Bugün de Bir 'Saklı Su'dur...". In Mehmet Kalpaklı (ed.). Osmanlı Divan Şiiri Üzerine Metinler. Yapı Kredi Yayınları. Vol. 1288. YKY. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-975-08-0164-8.

- Cengiz, Halil Erdoğan (1983). "Neşâtî". Divan Şiiri Antolojisi. Ankara: Bilgi Yayınevi. pp. 534–551.

- Dede, Mustafa Sâkıb (d. 1736) (n.d.). Sefîne-i nefîse-i Mevleviyye[Beautiful Ship of the Mevlevi Order].

- Şentürk, Ahmet Atilla (1999). "Neşâtî". Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi. Yapı Kredi Yayınları. Vol. 1287. YKY. pp. 555–559. ISBN 975-08-0163-6.