Related Research Articles

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, also known as Popé's Rebellion or Po'pay's Rebellion, was an uprising of most of the indigenous Pueblo people against the Spanish colonizers in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, larger than present-day New Mexico. Incidents of brutality and cruelty, coupled with persistent Spanish policies such as those that occurred in 1599 and resulted in The Ácoma Massacre, stoked animosity, gave rise to the eventual Revolt of 1680. The persecution and mistreatment of Pueblo people who adhered to traditional religious practices was the most despised of these. Scholars consider it the first Native American religious traditionalist revitalization movement. The Spaniards were resolved to abolish "pagan" forms of worship and replace them with Christianity. The Pueblo Revolt killed 400 Spaniards and drove the remaining 2,000 settlers out of the province. The Spaniards returned to New Mexico twelve years later.

The Mexican Inquisition was an extension of the Spanish Inquisition into New Spain. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was not only a political event for the Spanish, but a religious event as well. In the early 16th century, the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, and the Inquisition were in full force in most of Europe. The Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon had just conquered the last Muslim stronghold in the Iberian Peninsula, the kingdom of Granada, giving them special status within the Catholic realm, including great liberties in the conversion of the native peoples of Mesoamerica. When the Inquisition was brought to the New World, it was employed for many of the same reasons and against the same social groups as suffered in Europe itself, minus the Indigenous to a large extent. Almost all of the events associated with the official establishment of the Palace of the Inquisition occurred in Mexico City, where the Holy Office had its own major building. The official period of the Inquisition lasted from 1571 to 1820, with an unknown number of individuals prosecuted.

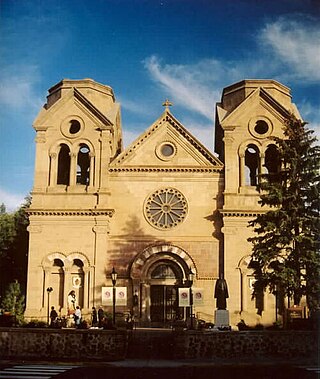

The Archdiocese of Santa Fe is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the southwestern region of the United States in the state of New Mexico. While the mother church, the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, is in the city of Santa Fe, its administrative center is in the city of Albuquerque. The Diocese comprises the counties of Rio Arriba, Taos, Colfax, Union, Mora, Harding, Los Alamos, Sandoval, Santa Fe, San Miguel, Quay, Bernalillo, Valencia, Socorro, Torrance, Guadalupe, De Baca, Roosevelt, and Curry. The current archbishop is John Charles Wester, who was installed on June 4, 2015.

Popé or Po'pay was a Tewa religious leader from Ohkay Owingeh, who led the Pueblo Revolt in 1680 against Spanish colonial rule. In the first successful revolt against the Spanish, the Pueblo expelled the colonists and kept them out of the territory for twelve years.

The history of New Mexico is based on archaeological evidence, attesting to the varying cultures of humans occupying the area of New Mexico since approximately 9200 BCE, and written records. The earliest peoples had migrated from northern areas of North America after leaving Siberia via the Bering Land Bridge. Artifacts and architecture demonstrate ancient complex cultures in this region.

The Piro pueblo of Senecú was the southernmost occupied pueblo in New Mexico prior to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. It was located on the west bank of the Rio Grande within sight of the Piro pueblo of San Pasqual. Colonial Spanish documents consistently place the pueblo opposite of Black Mesa, which is near San Marcial. Due to changes in the floodplain and the establishment of San Marcial, however, no surface remains of the pueblo survive in the area.

Juan Sabeata was a Jumano Indian leader in present day Texas who tried to forge an alliance with the Spanish or French to help his people fend off the encroachments of the Apaches on their territory.

The Tompiro Indians were Pueblo Indians living in New Mexico. They lived in several adobe villages east of the Rio Grande Valley in the Salinas region of New Mexico. Their settlements were abandoned and they were absorbed into other Pueblo Nations in the 1670s.

Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa Briceño y Berdugo (1621–1687) was a Lima-born soldier who served as governor of Spanish New Mexico in 1661–1664, following all his appointments to replace Bernardo López de Mendizábal in 1660.

Bernardo López de Mendizábal was a Spanish politician, soldier, and religious scholar, who served as governor of New Mexico between 1659–1660 and as alcalde mayor in Guayacocotla. Among López's acts as governor of New Mexico, he prohibited the Franciscan priests from forcing the Native Americans to work if they were not paying a salary and recognized their right to practice their religion. These acts caused disagreements with the Franciscan missionaries of New Mexico in their dealings with the Native Americans. He was indicted by the Inquisition on thirty-three counts of malfeasance and the practice of Judaism in 1660. He was replaced in the same year and his administration ended. He was arrested in 1663 and died as a prisoner in 1664.

Domingo Jironza Pétriz de Cruzate was a Spanish soldier who was Governor of New Mexico from 1683 to 1686, and again from 1689 to 1691. He came to office at a time a large part of the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México was independent of Spanish rule due to the Pueblo Revolt. With limited resources, he was unable to reconquer the province.

Estéban de Perea was a Spanish Franciscan friar who undertook missionary work in New Mexico, a province of New Spain, between 1610 and 1638. At times he was in conflict with the governors of the province. He has been called the "Father of the New Mexican Church".

Pedro de Peralta was Governor of New Mexico between 1610 and 1613 at a time when it was a province of New Spain. He formally founded the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1610. In August 1613 he was arrested and jailed for almost a year by the Franciscan friar Isidro Ordóñez. Later, he was vindicated by the Mexican Inquisition and held a number of other senior posts in the Spanish imperial administration.

Luis de Rosas was a soldier who served as the ninth Spanish Governor of New Mexico from 1637 until 1641, when he was then imprisoned and assassinated. During his administration, de Rosas clashed with the Franciscans, mainly because of his handling of the indigenous Americans, whom he forced to work for him or sold them as slaves. The Franciscans promoted a revolt of the citizens of New Mexico against him. De Rosas was imprisoned after an investigation relating to his position as governor. He was killed by soldiers while in prison.

Fernando de Argüello was a Spanish soldier who served as Governor of New Mexico, between 1644 and 1647.

Juan Manso de Contreras was the Spanish governor of New Mexico between 1656 and 1659. He was also a businessman who organized and led wagon trains carrying supplies from Mexico City and Parral, Chihuahua to New Mexico.

Alonso de Llanos y Posada González (1626-?) was a Franciscan missionary who worked among the Puebloans and the Hopi Indians in northern New Spain. He became the Custos (leader) of the Franciscans in New Mexico. Posada suppressed the indigenous religious practices of the Hopi and Puebloans. Posada was often in conflict with the secular government of New Mexico. He was the Franciscan leader in disputes with two New Mexican governors, Bernardo López de Mendizábal and Diego de Peñalosa, which led to their dismissal and prosecution. In the 17th century, the secular authorities and the Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico were often in conflict as they competed for power, wealth, and the resources and labor of the Indians. Historian John L. Kessell said, "No friar ever wielded the authority of the Inquisition in New Mexico" that Posada did.

The supply of Franciscan missions in New Mexico was the provision of supplies to Franciscan missionaries in the Spanish colony of New Mexico during the 17th century. Caravans of mule-drawn carts loaded with supplies left Mexico City every three years for a 1,600 miles (2,600 km) one-way journey to New Mexico. The journey required 18-months for a round trip. The supply trains were the main means of contact between New Mexico and the Spanish government in Mexico City. The cost of the supply trains was borne by the viceroy of New Spain. The Franciscans' goal was to convert to Christianity the American Indians in New Mexico, especially the Puebloans.

Salvador de Guerra was a Franciscan missionary to New Spain. He was investigated and sentenced in 1655 for abuse of the Hopi at his mission. Later, he served as secretary to Alonso de Posada, and was involved with the Inquisition investigation of Governor Bernardo López de Mendizábal.

Nicolás de Freitas was a Franciscan missionary to New Spain.

References

- ↑ The Spanish Colonial Settlement Landscapes of New Mexico, 1598-1680 Elinore M. Barrett - 2012 "There is no information about when Nicolás de Aguilar came to New Mexico (apparently having previously committed a murder in the Parral district of northern New Spain), but during 1659–61, when he was the ..."

- 1 2 3 López, Nancy; "Nicolas de Aguilar", My New Mexico Roots, accessed Aug 18, 2010

- ↑ Sanchez, Joseph P. “Nicolas de Aguilar and the Jurisdiction of Salinas in the Province of New Mexico, 1659-1662” Revista Complutense de Historia de América Vol. 22, Servicio de Publicaciones, UCM, Madrid, 1996

- ↑ Kiva, Cross, and Crown , p. 5, accessed Aug 18, 2010

- ↑ Sanchez, 149-155

- ↑ Gutierrez, Ramon A. When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away, Stanford: Stanford U Press, 1991, p. 123

- ↑ Weber, David J. What caused the Pueblo Revolt of 1680? Boston: Bedford, 1999, p. 120

- ↑ Hordes, Stanley M. To the End of the Earth: A History of the Crypto-Jews of New Mexico, New York: Columbia U Press, 2005 p. 151

- ↑ Knaut, Andrew L. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Norman: U of OK Press, 1997, p. 139.

- ↑ Sanchez, 139

- ↑ Chavez, Angelico (1954). Origins of New Mexico Families in the Spanish Colonial Period. Santa Fe, NM: Historical Society of New Mexico. p. 1.