Kaoru Mori is a Japanese manga artist from Tokyo and the creator of the manga series Shirley, Emma, and A Bride's Story. Many of her works are centered on female characters in the 19th century, such as a maid in Victorian Britain and a bride in Turkic Central Asia. She also wrote dōjinshi under the pen name Fumio Agata as a member of the dōjin circle Lady Maid.

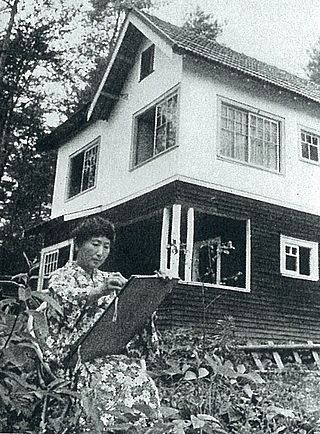

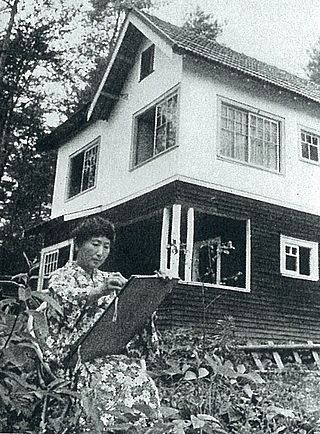

Shigeko Kubota was a Japanese video artist, sculptor and avant-garde performance artist, who mostly lived in New York City. She was one of the first artists to adopt the portable video camera Sony Portapak in 1970, likening it to a "new paintbrush." Kubota is known for constructing sculptural installations with a strong DIY aesthetic, which include sculptures with embedded monitors playing her original videos. She was a key member and influence on Fluxus, the international group of avant-garde artists centered on George Maciunas, having been involved with the group since witnessing John Cage perform in Tokyo in 1962 and subsequently moving to New York in 1964. She was closely associated with George Brecht, Jackson Mac Low, John Cage, Joe Jones, Nam June Paik, and Ay-O, among other members of Fluxus. Kubota was deemed "Vice Chairman" of the Fluxus Organization by Maciunas.

Toko Shinoda was a Japanese artist. Shinoda is best known for her abstract sumi ink paintings and prints. Shinoda’s oeuvre was predominantly executed using the traditional means and media of East Asian calligraphy, but her resulting abstract ink paintings and prints express a nuanced visual affinity with the bold black brushstrokes of mid-century Abstract Expressionism. In the postwar New York art world, Shinoda’s works were exhibited at the prominent art galleries including the Bertha Schaefer Gallery and the Betty Parsons Gallery. Shinoda remained active all her life and in 2013, she was honored with a touring retrospective exhibition at four venues in Gifu Prefecture to celebrate her 100th birthday. Shinoda has had solo exhibitions at the Seibu Museum at Art, Tokyo in 1989, the Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu in 1992, the Singapore Art Museum in 1996, the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in 2003, the Sogo Museum of Art in 2021, the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in 2022, and among many others. Shinoda's works are in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Harvard Art Museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, the Singapore Art Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the National Gallery of Victoria, and other leading museums of the world. Shinoda was also a prolific writer published more than 20 books.

Mel Chin is a conceptual visual artist. Motivated largely by political, cultural, and social circumstances, Chin works in a variety of art media to calculate meaning in modern life. Chin places art in landscapes, in public spaces, and in gallery and museum exhibitions, but his work is not limited to specific venues. Chin once stated: “Making objects and marks is also about making possibilities, making choices—and that is one of the last freedoms we have. To provide that is one of the functions of art.”

Takako Saito is a Japanese artist closely associated with Fluxus, the international collective of avant-garde artists that was active primarily in the 1960s and 1970s. Saito contributed a number of performances and artworks to the movement, which continue to be exhibited in Fluxus exhibitions to the present day. She was also deeply involved in the production of Fluxus edition works during the height of their production, and worked closely with George Maciunas.

Mieko Shiomi is a Japanese artist, composer, and performer who played a key role in the development of Fluxus. A co-founder of the seminal postwar Japanese experimental music collective Group Ongaku, she is known for her investigations of the nature and limits of sound, music, and auditory experiences. Her work has been widely circulated as Fluxus editions, featured in concert halls, museums, galleries, and non-traditional spaces, as well as being re-performed by other musicians and artists numerous times. She is best known for her work of the 1960s and early 1970s, especially Spatial Poem, Water Music, Endless Box, and the various instructions in Events & Games, all of which were produced as Fluxus editions. Now in her eighties, she continues to produce new work.

Chiharu Shiota is a Japanese performance and installation artist. Educated in Japan, Australia, and Germany, Shiota interweaves materiality and the psychic perception of the space to explore ideas around the body and flesh, personal narratives that engage with memory, territory, and alienation. Her signature installations, which consist of dazzling, intricate networks of threads stretching across gallery rooms, made the artist rise to fame in the 2000s. Shiota has exhibited worldwide and represented Japan in the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015.

Mami Kataoka is an art curator and writer.

Tiffany Chung is a Vietnamese American multimedia artist based in Houston, Texas. Chung is globally noted for her interdisciplinary and research-based practice, with cartographic works and installations that examine conflict, geopolitical partitioning, spatial transformation, environmental crisis, displacement, and forced migration, across time and terrain.

Firoz Mahmud is a Bangladeshi visual artist based in Japan. He was the first Bangladeshi fellow artist in research at Rijksakademie Van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. Mahmud's work has been exhibited at the following biennales: Sharjah Biennale, the first Bangkok Art Biennale, at the Dhaka Art Summit, Setouchi Triennale (BDP), the first Aichi Triennial, the Congo Biennale, the first Lahore Biennale, the Cairo Biennale, the Echigo-Tsumari Triennial, and the Asian Biennale.

Chiemi Amako, better known as Chiemi Hori, is a Japanese singer, actress, and entertainer represented by Horipro, and later Shochiku Geino. Her stage name is a hiragana version (ちえみ) of her given name written in kanji (智栄美), also pronounced Chiemi.

Bani Abidi is a Pakistani artist working with video, photography and drawing. She studied visual arts at the National College of Arts in Lahore and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2011, she was invited for the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin program, and since then has been residing in Berlin.

From Space to Environment was a postwar Japanese exhibition of contemporary art and design that was held on the eighth floor gallery of the Matsuya Department Store in Ginza, Tokyo, from November 11–16, 1966. It was organised by the multidisciplinary group Environment Society to promoted the marriage of art and technology.

Migishi Setsuko was a Japanese yōga (Western-style) painter. Known for employing vivid colors and bold strokes for still-life and landscape, Migishi contributed greatly to the establishment and elevation of the status of female artists in the Japanese art scene.

Mitsuko Tabe is a Fukuoka-based multimedia artist and was a key member in the avant-garde art group Kyūshū-ha, active between 1957 and 1968. In her Kyūshu-ha period, Tabe investigated the issues related to environmentalism and the aspects of female identity, including sexuality, procreation, and social advancement. She have worked in a variety of mediums, ranging from painting to installation to performance. After the group's dissolution, Tabe continued to work independently and advocate for the visibility of female artists in Kyūshū.

Cinthia Marcelle was born in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, in 1974. She is a Brazilian multimedia artist focusing in photography, video and installation work. She studied at the Universitadad Federal de Minas Gerais.

Thảo Nguyên Phan is a Vietnamese visual multimedia artist whose practice encompasses painting, filmmaking, and installation. She currently lives and works in Ho Chi Minh City and has exhibited widely in Vietnam and abroad. Drawing inspiration from both official and unofficial histories, Phan references her country's turbulent past while observing ambiguous issues in social convention, history, and tradition. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in Vietnam and abroad, at many public institutions, including the Factory Contemporary Art Centre, Ho Chi Minh City; Nha San Collective, Hanoi; Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai; Times Art Center in Berlin, Timișoara; and The Mistake Room, Los Angeles.

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi was a Japanese artist and art theorist based in Tokyo and Yokohama. Through his collaborations, writings, and teaching, he promoted an interdisciplinary avant-garde in postwar Japan that served as the foundation for the emergence of Japanese media art in the early 1980s, a field in which he remained active until his death. He represented Japan at the 1968 Venice Biennale and the 1975 Bienal de São Paulo, and served as producer for the Mitsui Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka.

Hideko Fukushima, born Aiko Fukushima, was a Japanese avant-garde painter born in the Nogizaka neighborhood of Tokyo. She was known as both a founding member of the Tokyo-based postwar avant-garde artist collective Jikken Kōbō and as a talented painter infamously recruited into Art Informel circles by the critic Michel Tapié during his 1957 trip to Japan. As a member of Jikken Kōbō she not only participated in art exhibitions, but also designed visuals for slide shows and costumes and set pieces for dances, theatrical performances, and recitals. She contributed to the postwar push that challenged both the boundaries between media and the nature of artistic collaboration, culminating in the intermedia experiments of Expo '70.

Toeko Tatsuno was a Japanese abstract painter, printmaker, and former professor at Tama Art University in Japan.