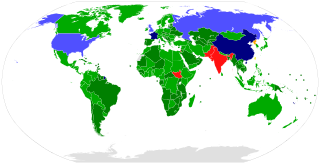

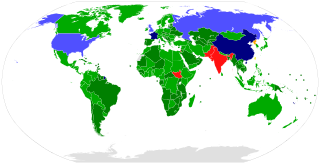

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament. Between 1965 and 1968, the treaty was negotiated by the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament, a United Nations-sponsored organization based in Geneva, Switzerland.

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as "Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT. Proliferation has been opposed by many nations with and without nuclear weapons, as governments fear that more countries with nuclear weapons will increase the possibility of nuclear warfare, de-stabilize international or regional relations, or infringe upon the national sovereignty of nation states.

Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term denuclearization is also used to describe the process leading to complete nuclear disarmament.

Arms control is a term for international restrictions upon the development, production, stockpiling, proliferation and usage of small arms, conventional weapons, and weapons of mass destruction. Arms control is typically exercised through the use of diplomacy which seeks to impose such limitations upon consenting participants through international treaties and agreements, although it may also comprise efforts by a nation or group of nations to enforce limitations upon a non-consenting country.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a nonprofit organization concerning science and global security issues resulting from accelerating technological advances that have negative consequences for humanity. The Bulletin publishes content at both a free-access website and a bi-monthly, nontechnical academic journal. The organization has been publishing continuously since 1945, when it was founded by former Manhattan Project scientists as the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago immediately following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The organization is also the keeper of the symbolic Doomsday Clock, the time of which is announced each January.

The Russian Federation is known to possess or have possessed three types of weapons of mass destruction: nuclear weapons, biological weapons, and chemical weapons. It is one of the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The United States is known to have possessed three types of weapons of mass destruction: nuclear weapons, chemical weapons, and biological weapons. The U.S. is the only country to have used nuclear weapons on another country, when it detonated two atomic bombs over two Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. It had secretly developed the earliest form of the atomic weapon during the 1940s under the title "Manhattan Project". The United States pioneered the development of both the nuclear fission and hydrogen bombs. It was the world's first and only nuclear power for four years, from 1945 until 1949, when the Soviet Union produced its own nuclear weapon. The United States has the second-largest number of nuclear weapons in the world, after the Russian Federation.

India possesses nuclear weapons and previously developed chemical weapons. Although India has not released any official statements about the size of its nuclear arsenal, recent estimates suggest that India has 160 nuclear weapons and has produced enough weapons-grade plutonium for up to 200 nuclear weapons. In 1999, India was estimated to have 800 kilograms (1,800 lb) of separated reactor-grade plutonium, with a total amount of 8,300 kilograms (18,300 lb) of civilian plutonium, enough for approximately 1,000 nuclear weapons. India has conducted nuclear weapons tests in a pair of series namely Pokhran I and Pokhran II.

Pakistan is one of nine states to possess nuclear weapons. Pakistan began development of nuclear weapons in January 1972 under Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who delegated the program to the Chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) Munir Ahmad Khan with a commitment to having the device ready by the end of 1976. Since PAEC, which consisted of over twenty laboratories and projects under reactor physicist Munir Ahmad Khan, was falling behind schedule and having considerable difficulty producing fissile material, Abdul Qadeer Khan, a metallurgist working on centrifuge enrichment for Urenco, joined the program at the behest of the Bhutto administration by the end of 1974. As pointed out by Houston Wood, "The most difficult step in building a nuclear weapon is the production of fissile material"; as such, this work in producing fissile material as head of the Kahuta Project was pivotal to Pakistan developing the capability to detonate a nuclear weapon by the end of 1984.

William C. Potter is Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar Professor of Nonproliferation Studies and Founding Director of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey (MIIS). He also directs the MIIS Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) is a multilateral export control regime. It is an informal political understanding among 35 member states that seek to limit the proliferation of missiles and missile technology. The regime was formed in 1987 by the G-7 industrialized countries. The MTCR seeks to limit the risks of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) by controlling exports of goods and technologies that could make a contribution to delivery systems for such weapons. In this context, the MTCR places particular focus on rockets and unmanned aerial vehicles capable of delivering a payload of at least 500 kg (1,100 lb) to a range of at least 300 km and on equipment, software, and technology for such systems.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, South Africa pursued research into weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons under the apartheid government. Six nuclear weapons were assembled. South African strategy was, if political and military instability in Southern Africa became unmanageable, to conduct a nuclear weapon test in a location such as the Kalahari desert, where an underground testing site had been prepared, to demonstrate its capability and resolve—and thereby highlight the peril of intensified conflict in the region—and then invite a larger power such as the United States to intervene.

South Korea has the raw materials and equipment to produce a nuclear weapon but has not opted to make one. In August 2004, South Korea revealed the extent of its highly secretive and sensitive nuclear research programs to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), including some experiments which were conducted without the obligatory reporting to the IAEA called for by South Korea's safeguards agreement. The failure to report was reported by the IAEA Secretariat to the IAEA Board of Governors; however, the IAEA Board of Governors decided to not make a formal finding of noncompliance. However, South Korea has continued on a stated policy of non-proliferation of nuclear weapons and has adopted a policy to maintain a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula.

The anti-nuclear movement is a social movement that opposes various nuclear technologies. Some direct action groups, environmental movements, and professional organisations have identified themselves with the movement at the local, national, or international level. Major anti-nuclear groups include Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Peace Action, Seneca Women's Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice and the Nuclear Information and Resource Service. The initial objective of the movement was nuclear disarmament, though since the late 1960s opposition has included the use of nuclear power. Many anti-nuclear groups oppose both nuclear power and nuclear weapons. The formation of green parties in the 1970s and 1980s was often a direct result of anti-nuclear politics.

The Shimon Peres Negev Nuclear Research Center is an Israeli nuclear installation located in the Negev desert, about thirteen kilometers south-east of the city of Dimona. In August 2018, it was renamed after the late President and Prime Minister of Israel, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Shimon Peres.

Henry D. Sokolski is the founder and executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, a Washington-based think tank promoting a better understanding of strategic weapons proliferation issues among policymakers, scholars, and the media. He teaches as an adjunct professor at The Institute of World Politics in Washington, D.C. and at the University of Utah and has an appointment as Senior Fellow for Nuclear Security Studies at the University of California at San Diego, School of Global Policy and Strategy.

Nuclear history of the United States describes the history of nuclear affairs in the United States whether civilian or military.

Prior to 1991, Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union and had Soviet nuclear weapons in its territory. On December 1, 1991, Ukraine, the second most powerful republic in the Soviet Union (USSR), voted overwhelmingly for independence, which ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union staying together even on a limited scale. More than 90% of the electorate expressed their support for Ukraine's declaration of independence, and they elected the chairman of the parliament, Leonid Kravchuk, as the first president of the country. At the meetings in Brest, Belarus on December 8, and in Alma Ata on December 21, the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine formally dissolved the Soviet Union and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Jeffrey Lewis is an American expert in nuclear nonproliferation and geopolitics, currently an Adjunct Professor at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, and director of the CNS East Asia Nonproliferation Program. He has written two books on China's nuclear weapons, and numerous journal and magazine articles, blog posts, and podcasts on nonproliferation and related topics.