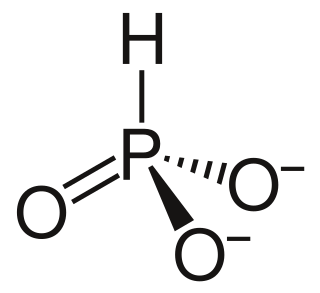

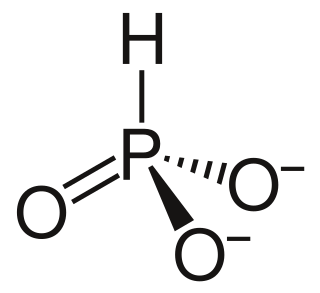

A phosphite anion or phosphite in inorganic chemistry usually refers to [HPO3]2− but includes [H2PO3]− ([HPO2(OH)]−). These anions are the conjugate bases of phosphorous acid (H3PO3). The corresponding salts, e.g. sodium phosphite (Na2HPO3) are reducing in character.

Phosphorus trifluoride (formula PF3), is a colorless and odorless gas. It is highly toxic and reacts slowly with water. Its main use is as a ligand in metal complexes. As a ligand, it parallels carbon monoxide in metal carbonyls, and indeed its toxicity is due to its binding with the iron in blood hemoglobin in a similar way to carbon monoxide.

The coordination geometry of an atom is the geometrical pattern defined by the atoms around the central atom. The term is commonly applied in the field of inorganic chemistry, where diverse structures are observed. The coordination geometry depends on the number, not the type, of ligands bonded to the metal centre as well as their locations. The number of atoms bonded is the coordination number. The geometrical pattern can be described as a polyhedron where the vertices of the polyhedron are the centres of the coordinating atoms in the ligands.

In chemistry an antimonate is a compound which contains a metallic element, oxygen, and antimony in an oxidation state of +5. These compounds adopt polymeric structures with M-O-Sb linkages. They can be considered to be derivatives of the hypothetical antimonic acid H3SbO4, or combinations of metal oxides and antimony pentoxide, Sb2O5.

Iron shows the characteristic chemical properties of the transition metals, namely the ability to form variable oxidation states differing by steps of one and a very large coordination and organometallic chemistry: indeed, it was the discovery of an iron compound, ferrocene, that revolutionalized the latter field in the 1950s. Iron is sometimes considered as a prototype for the entire block of transition metals, due to its abundance and the immense role it has played in the technological progress of humanity. Its 26 electrons are arranged in the configuration [Ar]3d64s2, of which the 3d and 4s electrons are relatively close in energy, and thus it can lose a variable number of electrons and there is no clear point where further ionization becomes unprofitable.

Gold(V) fluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula Au2F10. This fluoride compound features gold in its highest known oxidation state. This red solid dissolves in hydrogen fluoride but these solutions decompose, liberating fluorine.

Phosphorus pentafluoride, PF5, is a phosphorus halide. It is a colourless, toxic gas that fumes in air.

John Stuart Anderson FRS, FAA, was a British and Australian scientist who was Professor of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne and Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Oxford.

Barium bromide is the chemical compound with the formula BaBr2. It is ionic and hygroscopic in nature.

Iodine pentoxide is the chemical compound with the formula I2O5. This iodine oxide is the anhydride of iodic acid, and the only stable oxide of iodine. It is produced by dehydrating iodic acid at 200 °C in a stream of dry air:

Dithionic acid, H2S2O6, is a chemical compound known only in solution.

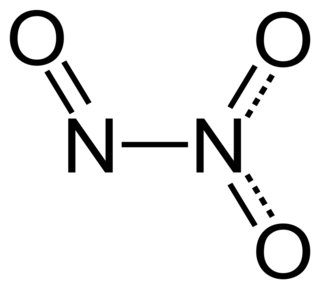

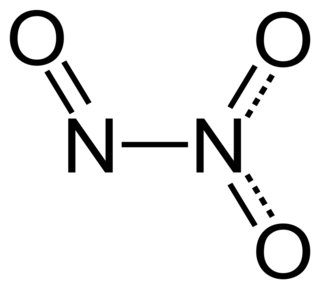

Dinitrogen trioxide is the inorganic compound with the formula N2O3. It is a nitrogen oxide. It forms upon mixing equal parts of nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide and cooling the mixture below −21 °C (−6 °F):

Stock nomenclature for inorganic compounds is a widely used system of chemical nomenclature developed by the German chemist Alfred Stock and first published in 1919. In the "Stock system", the oxidation states of some or all of the elements in a compound are indicated in parentheses by Roman numerals.

Triphosphane or triphosphine is an inorganic compound having the chemical formula HP(PH2)2. It can be generated from diphosphine but is highly unstable at room temperature:

Harry Julius Emeléus CBE, FRS was an English inorganic chemist and a professor in the department of chemistry, Cambridge University.

Hexasulfur is an inorganic chemical with the chemical formula S6. This allotrope was first prepared by M. R. Engel in 1891 by treating thiosulfate with HCl. Cyclo-S6 is orange-red and forms a rhombohedral crystal. It is called ρ-sulfur, ε-sulfur, Engel's sulfur and Aten's sulfur. Another method of preparation involves the reaction of a polysulfane with sulfur monochloride:

Germanium(IV) nitride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Ge3N4. It can be produced through the reaction of germanium and ammonia:

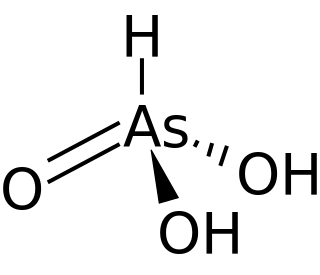

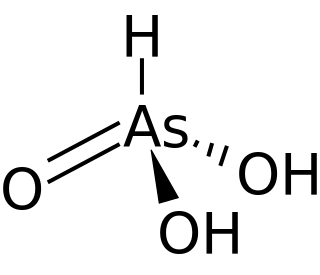

Arsonic acid is the simplest of the arsonic acids. It is a hypothetical compound, although the tautomeric arsenious acid (As(OH)3) is well established. In contrast to the instability of HAsO(OH)2, the phosphorus compound with analogous stoichiometry exists as the tetrahedral tautomer. Similarly, organic derivatives such as phenylarsonic acid are tetrahedral with pentavalent central atom.

The Inorganic Chemistry Division of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), also known as Division II, deals with all aspects of inorganic chemistry, including materials and bioinorganic chemistry, and also with isotopes, atomic weights and the periodic table. It furthermore advises the Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division on issues dealing with inorganic compounds and materials. For the general public, the most visible result of the division's work is that it evaluates and advises the IUPAC on names and symbols proposed for new elements that have been approved for addition to the periodic table. For the scientific end educational community the work on isotopic abundances and atomic weights is of fundamental importance as these numbers are continuously checked and updated.

Alfred Gavin Maddock (1917–2009) was an English inorganic chemist, radiochemist and spectroscopist who worked on the Tube Alloys Project and the Manhattan Project during World War II. Those projects resulted in the development of the atomic bomb. He may be best known for, during World War II, spilling Canada's entire supply of plutonium which was 10 milligrams onto a wooden laboratory bench, and for recovered 9 and a half milligrams of plutonium. He recovered it by wet chemistry. He also had a distinguished, though less eventful, post-war academic career.