Tocobaga was the name of a chiefdom of Native Americans, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-day city of Tampa and northern Pinellas County. The exact location of the principal town is believed to be the archeological Safety Harbor site. This is the namesake for the Safety Harbor culture, of which the Tocobaga are the most well-known group.

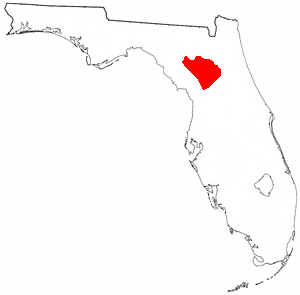

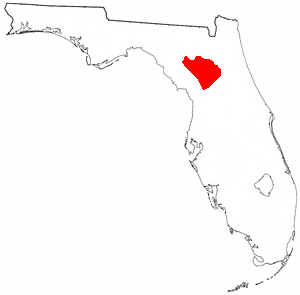

The Potano tribe lived in north-central Florida at the time of first European contact. Their territory included what is now Alachua County, the northern half of Marion County and the western part of Putnam County. This territory corresponds to that of the Alachua culture, which lasted from about 700 until 1700. The Potano were among the many tribes of the Timucua people, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language.

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their heartland extended from about the Altamaha River in Georgia to south of the mouth of the St. John's River, covering the Sea Islands and the inland waterways, Intracoastal. and much of present-day Jacksonville. At the time of contact with Europeans, there were two major chiefdoms among the Mocama, the Saturiwa and the Tacatacuru, each of which evidently had authority over multiple villages. The Saturiwa controlled chiefdoms stretching to modern day St. Augustine, but the native peoples of these chiefdoms have been identified by Pareja as speaking Agua Salada, which may have been a distinct dialect.

Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the Kingdom of Spain established a number of missions throughout La Florida in order to convert the Native Americans to Roman Catholicism, to facilitate control of the area, and to obstruct regional colonization by other Protestants, particularly, those from England and France. Spanish Florida originally included much of what is now the Southeastern United States, although Spain never exercised long-term effective control over more than the northern part of what is now the State of Florida from present-day St. Augustine to the area around Tallahassee, southeastern Georgia, and some coastal settlements, such as Pensacola, Florida. A few short-lived missions were established in other locations, including Mission Santa Elena in present-day South Carolina, around the Florida peninsula, and in the interior of Georgia and Alabama.

The Fig Springs mission site (8CO1) is an archaeological site in Ichetucknee Springs State Park, in Columbia County, Florida. It has been identified as the site of a Spanish mission to the Timucua people of the region, dating to the first half of the 17th century. Found within the historical territory of the Timucua people known as the Northern Utina, it is thought to be the Mission San Martín de Timucua, also known as San Martín de Ayacuto, which was founded in the important Northern Utina village of Ayacuto in 1608.

Santa Fe de Toloca was a Spanish mission that existed near the Santa Fe River in the northwestern part of what is now Alachua County, Florida, United States during the 17th century. It became an important place on the camino real connecting St. Augustine with Apalachee Province, which was centered on the site of present-day Tallahassee, Florida. The site that the Santa Fe de Toloca mission occupied in the first half of the 17th century was partially excavated in the 1980s.

Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact. The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

The Indigenous peoples of Florida lived in what is now known as Florida for more than 12,000 years before the time of first contact with Europeans. However, the indigenous Floridians living east of the Apalachicola River had largely died out by the early 18th century. Some Apalachees migrated to Louisiana, where their descendants now live; some were taken to Cuba and Mexico by the Spanish in the 18th century, and a few may have been absorbed into the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes.

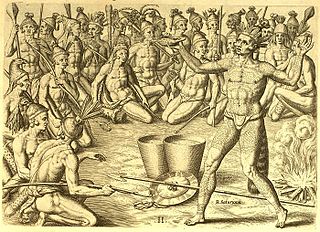

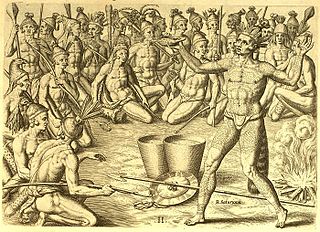

The Saturiwa were a Timucua chiefdom centered on the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. They were the largest and best attested chiefdom of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of present-day northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. They were a prominent political force in the early days of European settlement in Florida, forging friendly relations with the French Huguenot settlers at Fort Caroline in 1564 and later becoming heavily involved in the Spanish mission system.

The Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) were a Timucua people of northeastern Florida. They lived in the St. Johns River watershed north of Lake George, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language also known as Agua Dulce.

The Yustaga were a Timucua people of what is now northwestern Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The westernmost Timucua group, they lived between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers in the Florida Panhandle, just east of the Apalachee people. A dominant force in regional tribal politics, they may have been organized as a loose regional chiefdom consisting of up to eight smaller local chiefdoms.

Ocale was the name of a town in Florida visited by the Hernando de Soto expedition, and of a putative chiefdom of the Timucua people. The town was probably close to the Withlacoochee River at the time of de Soto's visit, and may have later been moved to the Oklawaha River.

San Buenaventura de Potano was a Spanish mission near Orange Lake in southern Alachua County or northern Marion County, Florida, located on the site where the town of Potano had been located when it was visited by Hernando de Soto in 1539. The Richardson/UF Village Site (8AL100), in southern Alachua County, has been proposed as the location of the town and mission.

Tomás Menéndez Márquez y Pedroso (1643–1706) was an official in the government of Spanish Florida, and owner, with his brothers, of the largest ranch in Spanish Florida. He was captured by pirates in 1682 and held for ransom, but was rescued by the Timucua.

Arapaha was a Timucua town on the Alapaha River in the 17th century. The name was also sometimes used to designate a province or sub-province in Spanish Florida.

The Suwannee Valley culture is defined as a Late Woodland Southeast period archaeological culture in north Florida, dating from around 750 to European contact. The core area of the culture was found in an area roughly corresponding to present-day Suwannee and southern and central Columbia counties. It was preceded by the McKeithen Weeden Island culture and followed by the Spanish mission period Leon-Jefferson culture.

The La Chua ranch was the largest cattle ranch in Spanish Florida in the 17th century. Cattle ranching became an important part of the economy of Spanish Florida over the course of the 17th century. The La Chua ranch was founded in the middle of the 17th century, and by the end of that century accounted for one-third of the cattle in the colony. Raids by the English of the Province of Carolina and their native allies led to the abandonment of the La Chua ranch early in the 18th century.

Cattle ranching was an important industry in Spanish Florida in the second half of the seventeenth century. The Spanish were in Florida for almost a century before ranching became widespread in the colony. Late in the seventeenth century, ranches were located along the middle St. Johns River, in Potano Province, and in Apalachee Province. Ranches flourished despite conflicts with the native people of Florida. Attacks by the English colony, the Province of Carolina, and its native allies brought an abrupt end to ranching in Florida at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The Oconi or Ocone were a Timucua people that spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. They lived in a chiefdom on the margin of or in the Okefenokee Swamp in southeastern Georgia. The Oconi first appeared in Spanish records in 1602, but a mission was not established until at least a decade later, with the first record of a mission in 1630. The Spanish twice attempted to relocate the Oconi people to other missions, in 1645 and 1655. The Oconi disappeared from Spanish records after 1655.