Related Research Articles

San Juan del Puerto was a Spanish Franciscan mission founded before 1587 on Fort George Island, near the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. It was founded to serve the Saturiwa, a Timucua tribe who lived around the mouth of the St. Johns. It was organized by separating them into nine smaller villages. It has an important place in the study of the Timucua, as the place where Francisco Pareja undertook his work on the Timucua language.

The Icafui people were a Timucua people of southeastern Georgia, who were closely related if not synonymous with the Cascangue people. Exceptionally little is known about the Icafui, other than their general location and the fact that they spoke a dialect of Timucua called "Itafi" along with the Ibi.

Timucua is a language isolate formerly spoken in northern and central Florida and southern Georgia by the Timucua peoples. Timucua was the primary language used in the area at the time of Spanish colonization in Florida. Differences among the nine or ten Timucua dialects were slight, and appeared to serve mostly to delineate band or tribal boundaries. Some linguists suggest that the Tawasa of what is now northern Alabama may have spoken Timucua, but this is disputed.

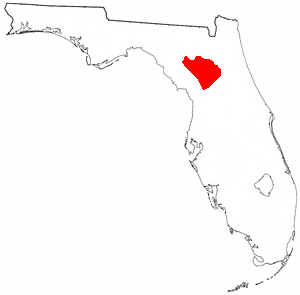

The Potano tribe lived in north-central Florida at the time of first European contact. Their territory included what is now Alachua County, the northern half of Marion County and the western part of Putnam County. This territory corresponds to that of the Alachua culture, which lasted from about 700 until 1700. The Potano were among the many tribes of the Timucua people, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language.

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their heartland extended from about the Altamaha River in Georgia to south of the mouth of the St. John's River, covering the Sea Islands and the inland waterways, Intracoastal. and much of present-day Jacksonville. At the time of contact with Europeans, there were two major chiefdoms among the Mocama, the Saturiwa and the Tacatacuru, each of which evidently had authority over multiple villages. The Saturiwa controlled chiefdoms stretching to modern day St. Augustine, but the native peoples of these chiefdoms have been identified by Pareja as speaking Agua Salada, which may have been a distinct dialect.

Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the Kingdom of Spain established a number of missions throughout La Florida in order to convert the Native Americans to Roman Catholicism, to facilitate control of the area, and to obstruct regional colonization by other Protestants, particularly, those from England and France. Spanish Florida originally included much of what is now the Southeastern United States, although Spain never exercised long-term effective control over more than the northern part of what is now the State of Florida from present-day St. Augustine to the area around Tallahassee, southeastern Georgia, and some coastal settlements, such as Pensacola, Florida. A few short-lived missions were established in other locations, including Mission Santa Elena in present-day South Carolina, around the Florida peninsula, and in the interior of Georgia and Alabama.

The Spanish missions in Georgia comprised a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics in order to spread the Christian doctrine among the Guale and various Timucua peoples in southeastern Georgia.

San Lorenzo de Ibihica was a Spanish Franciscan mission built in the early 17th century in the southeast of the present-day U.S. state of Georgia. It was part of Spain's effort to colonize the region of Spanish Florida and convert the Timucua to Catholicism. It served the Ibi people, also known as the Yui or Ibihica, a Timucua group of the area.

Mission San Pedro de Mocama was a Spanish colonial Franciscan mission on Cumberland Island, on the coast of the present-day U.S. state of Georgia, from the late 16th century through the mid-17th century. It was built to serve the Tacatacuru, a Mocama Timucua people.

Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

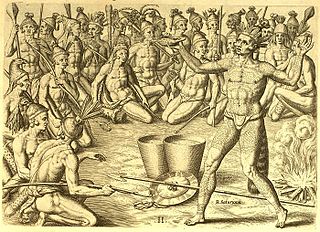

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact. The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

The Saturiwa were a Timucua chiefdom centered on the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. They were the largest and best attested chiefdom of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of present-day northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. They were a prominent political force in the early days of European settlement in Florida, forging friendly relations with the French Huguenot settlers at Fort Caroline in 1564 and later becoming heavily involved in the Spanish mission system.

The Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) were a Timucua people of northeastern Florida. They lived in the St. Johns River watershed north of Lake George, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language also known as Agua Dulce.

Tacatacuru was a Timucua chiefdom located on Cumberland Island in what is now the U.S. state of Georgia in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was one of two chiefdoms of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of southeastern Georgia and northern Florida.

The Ibi, also known as the Yui or Ibihica, were a Timucua chiefdom in the present-day U.S. state of Georgia during the 16th and 17th centuries. They lived in southeastern Georgia, about 50 miles from the coast. Like their neighbors, the Icafui tribe, they spoke a dialect of the Timucua language called Itafi.

The Yustaga were a Timucua people of what is now northwestern Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The westernmost Timucua group, they lived between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers in the Florida Panhandle, just east of the Apalachee people. A dominant force in regional tribal politics, they may have been organized as a loose regional chiefdom consisting of up to eight smaller local chiefdoms.

Benito Ruíz de Salazar Vallecilla was twice governor of Spanish Florida, from 1645 to 1646 and from 1648 to 1651.

San Buenaventura de Potano was a Spanish mission near Orange Lake in southern Alachua County or northern Marion County, Florida, located on the site where the town of Potano had been located when it was visited by Hernando de Soto in 1539. The Richardson/UF Village Site (8AL100), in southern Alachua County, has been proposed as the location of the town and mission.

San Buenaventura de Guadalquini or San Buenaventura de Boadalquivi was a Spanish mission located on St. Simon's Island, Georgia, United States from between 1597 and 1609 until 1684, when pirates burned the mission and its town. The mission moved to the north side of the St. Johns River near its mouth, in present day Duval County, Florida under the name of Santa Cruz de Guadalquini or Santa Cruz y San Buenaventura de Guadalquini for a few years before merging with the mission San Juan del Puerto.

Arapaha was a Timucua town on the Alapaha River in the 17th century. The name was also sometimes used to designate a province or sub-province in Spanish Florida.

References

- ↑ Hann 1996, pp. 5, 155–156, 237.

- ↑ Milanich 1999, p. 26, 49.

- ↑ Worth 1998, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Hann 1996, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 Hann 1996, p. 155.

- ↑ Milanich 1978, p. 59.

- ↑ Hann 1996, p. 5.

- ↑ Hann 1996, p. 94.

- 1 2 Hann 1996, p. 156.

- ↑ Hann 1996, p. 95, 333.

- ↑ Milanich 1999, p. 121.

- ↑ Hann 1996, p. 8.

- ↑ Hann 1996, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Hann 1996, pp. 156–157, 236–237.