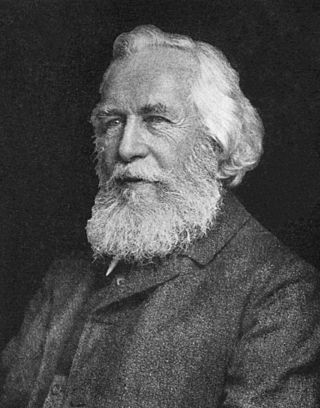

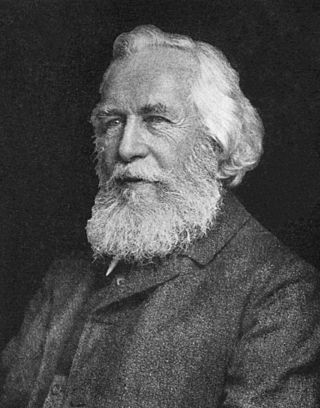

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms and coined many terms in biology, including ecology, phylum, phylogeny, and Protista. Haeckel promoted and popularised Charles Darwin's work in Germany and developed the debunked but influential recapitulation theory, falsely claiming that an individual organism's biological development, or ontogeny, parallels and summarizes its species' evolutionary development, or phylogeny, using incorrectly redrawn images of human embryonic development, images which heavily influenced the public to believe in the theory of evolution. Whether he intentionally falsified the images or drew them poorly by accident is a matter of debate.

Embryo drawing is the illustration of embryos in their developmental sequence. In plants and animals, an embryo develops from a zygote, the single cell that results when an egg and sperm fuse during fertilization. In animals, the zygote divides repeatedly to form a ball of cells, which then forms a set of tissue layers that migrate and fold to form an early embryo. Images of embryos provide a means of comparing embryos of different ages, and species. To this day, embryo drawings are made in undergraduate developmental biology lessons.

Neoteny, also called juvenilization, is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny in modern humans is more significant than in other primates. In progenesis or paedogenesis, sexual development is accelerated.

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an animal, from fertilization to gestation or hatching (ontogeny), goes through stages resembling or representing successive adult stages in the evolution of the animal's remote ancestors (phylogeny). It was formulated in the 1820s by Étienne Serres based on the work of Johann Friedrich Meckel, after whom it is also known as the Meckel–Serres law.

Ontogeny is the origination and development of an organism, usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the study of the entirety of an organism's lifespan.

Evolutionary developmental biology is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolved.

This is a list of topics in evolutionary biology.

Carl Gegenbaur was a German anatomist and professor who demonstrated that the field of comparative anatomy offers important evidence supporting of the theory of evolution. As a professor of anatomy at the University of Jena (1855–1873) and at the University of Heidelberg (1873–1903), Carl Gegenbaur was a strong supporter of Charles Darwin's theory of organic evolution, having taught and worked, beginning in 1858, with Ernst Haeckel, eight years his junior.

In evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This leads to changes in the size, shape, characteristics and even presence of certain organs and features. It is contrasted with heterotopy, a change in spatial positioning of some process in the embryo, which can also create morphological innovation. Heterochrony can be divided into intraspecific heterochrony, variation within a species, and interspecific heterochrony, phylogenetic variation, i.e. variation of a descendant species with respect to an ancestral species.

In biology, saltation is a sudden and large mutational change from one generation to the next, potentially causing single-step speciation. This was historically offered as an alternative to Darwinism. Some forms of mutationism were effectively saltationist, implying large discontinuous jumps.

A body plan, Bauplan, or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book Embryos and Ancestors. He was director of the Natural History Museum, London, president of the Linnean Society of London, and a winner of the Royal Society's Darwin Medal for his studies on evolution.

Caenogenesis is the introduction during embryonic development of characters or structure not present in the earlier evolutionary history of the strain or species, as opposed to palingenesis. Notable examples include the addition of the placenta in mammals.

Walter Garstang FLS FZS, a Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford and Professor of Zoology at the University of Leeds, was one of the first to study the functional biology of marine invertebrate larvae. His best known works on marine larvae were his poems published as Larval Forms and Other Zoological Verses, especially The Ballad of the Veliger. They describe the form and function of several marine larvae as well as illustrating some controversies in evolutionary biology of the time.

Gerd B. Müller is an Austrian biologist who is emeritus professor at the University of Vienna where he was the head of the Department of Theoretical Biology in the Center for Organismal Systems Biology. His research interests focus on vertebrate limb development, evolutionary novelties, evo-devo theory, and the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. He is also concerned with the development of 3D based imaging tools in developmental biology.

Susan Oyama is a psychologist and philosopher of science, currently professor emerita at the John Jay College and CUNY Graduate Center in New York City.

Alessandro Minelli is an Italian biologist, formerly a professor of zoology in the Faculty of Mathematical, Physical and Natural Sciences of the University of Padova, mainly working on evo-devo subjects.

Heterotopy is an evolutionary change in the spatial arrangement of an animal's embryonic development, complementary to heterochrony, a change to the rate or timing of a development process. It was first identified by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 and has remained less well studied than heterochrony.

In developmental biology, von Baer's laws of embryology are four rules proposed by Karl Ernst von Baer to explain the observed pattern of embryonic development in different species.

Human evolutionary developmental biology or informally human evo-devo is the human-specific subset of evolutionary developmental biology. Evolutionary developmental biology is the study of the evolution of developmental processes across different organisms. It is utilized within multiple disciplines, primarily evolutionary biology and anthropology. Groundwork for the theory that "evolutionary modifications in primate development might have led to … modern humans" was laid by Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Ernst Haeckel, Louis Bolk, and Adolph Schultz. Evolutionary developmental biology is primarily concerned with the ways in which evolution affects development, and seeks to unravel the causes of evolutionary innovations.