A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word laser is an anacronym that originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. The first laser was built in 1960 by Theodore Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories, based on theoretical work by Charles H. Townes and Arthur Leonard Schawlow.

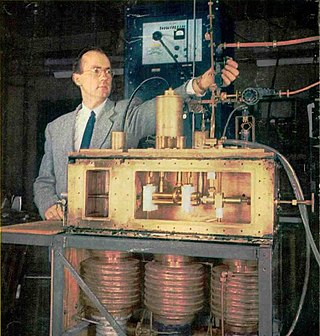

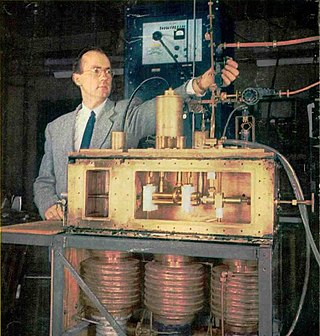

A maser is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves (microwaves), through amplification by stimulated emission. The term is an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. First suggested by Joseph Weber, the first maser was built by Charles H. Townes, James P. Gordon, and Herbert J. Zeiger at Columbia University in 1953. Townes, Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov were awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics for theoretical work leading to the maser. Masers are used as the timekeeping device in atomic clocks, and as extremely low-noise microwave amplifiers in radio telescopes and deep-space spacecraft communication ground stations.

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets electromagnetic spectra. In narrower contexts, spectroscopy is the precise study of color as generalized from visible light to all bands of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter–matter and light–matter interactions, at the scale of one or a few atoms and energy scales around several electron volts. The three areas are closely interrelated. AMO theory includes classical, semi-classical and quantum treatments. Typically, the theory and applications of emission, absorption, scattering of electromagnetic radiation (light) from excited atoms and molecules, analysis of spectroscopy, generation of lasers and masers, and the optical properties of matter in general, fall into these categories.

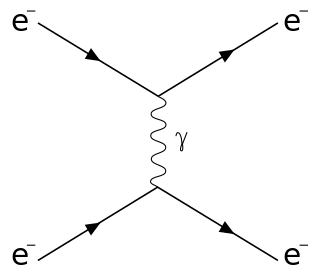

Ionization is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule is called an ion. Ionization can result from the loss of an electron after collisions with subatomic particles, collisions with other atoms, molecules, electrons, positrons, protons, antiprotons and ions, or through the interaction with electromagnetic radiation. Heterolytic bond cleavage and heterolytic substitution reactions can result in the formation of ion pairs. Ionization can occur through radioactive decay by the internal conversion process, in which an excited nucleus transfers its energy to one of the inner-shell electrons causing it to be ejected.

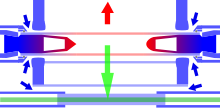

Laser cooling includes several techniques where atoms, molecules, and small mechanical systems are cooled with laser light. The directed energy of lasers is often associated with heating materials, e.g. laser cutting, so it can be counterintuitive that laser cooling often results in sample temperatures approaching absolute zero. It is a routine step in many atomic physics experiments where the laser-cooled atoms are then subsequently manipulated and measured, or in technologies, such as atom-based quantum computing architectures. Laser cooling relies on the change in momentum when an object, such as an atom, absorbs and re-emits a photon. For example, if laser light illuminates a warm cloud of atoms from all directions and the laser's frequency is tuned below an atomic resonance, the atoms will be cooled. This common type of laser cooling relies on the Doppler effect where individual atoms will preferentially absorb laser light from the direction opposite to the atom's motion. The absorbed light is re-emitted by the atom in a random direction. After repeated emission and absorption of light the net effect on the cloud of atoms is that they will expand more slowly. The slower expansion reflects a decrease in the velocity distribution of the atoms, which corresponds to a lower temperature and therefore the atoms have been cooled. For an ensemble of particles, their thermodynamic temperature is proportional to the variance in their velocity, therefore the lower the distribution of velocities, the lower temperature of the particles.

In atomic physics, hyperfine structure is defined by small shifts in otherwise degenerate electronic energy levels and the resulting splittings in those electronic energy levels of atoms, molecules, and ions, due to electromagnetic multipole interaction between the nucleus and electron clouds.

In physics, Raman scattering or the Raman effect is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrational energy being gained by a molecule as incident photons from a visible laser are shifted to lower energy. This is called normal Stokes-Raman scattering.

Resolved sideband cooling is a laser cooling technique allowing cooling of tightly bound atoms and ions beyond the Doppler cooling limit, potentially to their motional ground state. Aside from the curiosity of having a particle at zero point energy, such preparation of a particle in a definite state with high probability (initialization) is an essential part of state manipulation experiments in quantum optics and quantum computing.

Atomic vapor laser isotope separation, or AVLIS, is a method by which specially tuned lasers are used to separate isotopes of uranium using selective ionization of hyperfine transitions. A similar technology, using molecules instead of atoms, is molecular laser isotope separation (MLIS).

Optical molasses is a laser cooling technique that can cool neutral atoms to as low as a few microkelvin, depending on the atomic species. An optical molasses consists of 3 pairs of counter-propagating orthogonally polarized laser beams intersecting in the region where the atoms are present. The main difference between an optical molasses (OM) and a magneto-optical trap (MOT) is the absence of magnetic field in the former. Unlike a MOT, an OM provides only cooling and no trapping.

Doppler cooling is a mechanism that can be used to trap and slow the motion of atoms to cool a substance. The term is sometimes used synonymously with laser cooling, though laser cooling includes other techniques.

In atomic, molecular, and optical physics, a magneto-optical trap (MOT) is an apparatus which uses laser cooling and a spatially-varying magnetic field to create a trap which can produce samples of cold, neutral atoms. Temperatures achieved in a MOT can be as low as several microkelvin, depending on the atomic species, which is two or three times below the photon recoil limit. However, for atoms with an unresolved hyperfine structure, such as 7Li, the temperature achieved in a MOT will be higher than the Doppler cooling limit.

In condensed matter physics, an ultracold atom is an atom with a temperature near absolute zero. At such temperatures, an atom's quantum-mechanical properties become important.

The manipulation of atoms using optical fields is a vital and fundamental area of research within the field of atomic physics. This research revolves around leveraging the distinct characteristics of laser light and coherent optical fields to achieve precise control over various aspects of atomic systems. These aspects encompass regulating atomic motion, positioning atoms, manipulating internal states, and facilitating intricate interactions with neighboring atoms and photons. The utilization of optical fields provides a powerful toolset for exploring and understanding the quantum behavior of atoms and opens up promising avenues for applications in atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions between such states they interact with a very specific frequency of electromagnetic radiation. This phenomenon serves as the basis for the International System of Units' (SI) definition of a second:

The second, symbol s, is the SI unit of time. It is defined by taking the fixed numerical value of the caesium frequency, , the unperturbed ground-state hyperfine transition frequency of the caesium-133 atom, to be 9192631770 when expressed in the unit Hz, which is equal to s−1.

In atomic physics, Raman cooling is a sub-recoil cooling technique that allows the cooling of atoms using optical methods below the limitations of Doppler cooling, Doppler cooling being limited by the recoil energy of a photon given to an atom. This scheme can be performed in simple optical molasses or in molasses where an optical lattice has been superimposed, which are called respectively free space Raman cooling and Raman sideband cooling. Both techniques make use of Raman scattering of laser light by the atoms.

Sub-Doppler cooling is a class of laser cooling techniques that reduce the temperature of atoms and molecules below the Doppler cooling limit. In experiment implementation, Doppler cooling is limited by the broad natural linewidth of the lasers used in cooling. Regardless of the transition used, however, Doppler cooling processes have an intrinsic cooling limit that is characterized by the momentum recoil from the emission of a photon from the particle. This is called the recoil temperature and is usually far below the linewidth-based limit mentioned above.

Gray molasses is a method of sub-Doppler laser cooling of atoms. It employs principles from Sisyphus cooling in conjunction with a so-called "dark" state whose transition to the excited state is not addressed by the resonant lasers. Ultracold atomic physics experiments on atomic species with poorly-resolved hyperfine structure, like isotopes of lithium and potassium, often utilize gray molasses instead of Sisyphus cooling as a secondary cooling stage after the ubiquitous magneto-optical trap (MOT) to achieve temperatures below the Doppler limit. Unlike a MOT, which combines a molasses force with a confining force, a gray molasses can only slow but not trap atoms; hence, its efficacy as a cooling mechanism lasts only milliseconds before further cooling and trapping stages must be employed.

Polarization gradient cooling is a technique in laser cooling of atoms. It was proposed to explain the experimental observation of cooling below the doppler limit. Shortly after the theory was introduced experiments were performed that verified the theoretical predictions. While Doppler cooling allows atoms to be cooled to hundreds of microkelvin, PG cooling allows atoms to be cooled to a few microkelvin or less.