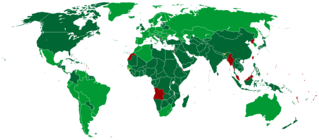

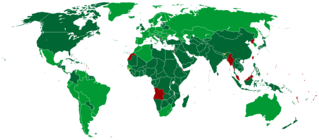

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it was instituted on 3 September 1981 and has been ratified by 189 states. Over fifty countries that have ratified the Convention have done so subject to certain declarations, reservations, and objections, including 38 countries who rejected the enforcement article 29, which addresses means of settlement for disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the convention. Australia's declaration noted the limitations on central government power resulting from its federal constitutional system. The United States and Palau have signed, but not ratified the treaty. The Holy See, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, and Tonga are not signatories to CEDAW.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is a body of experts that monitor and report on the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Human rights are largely respected in Switzerland, one of Europe's oldest democracies. Switzerland is often at or near the top in international rankings of civil liberties and political rights observance. Switzerland places human rights at the core of the nation's value system, as represented in its Federal Constitution. As described in its FDFA's Foreign Policy Strategy 2016-2019, the promotion of peace, mutual respect, equality and non-discrimination are central to the country's foreign relations.

Nauru is a small island country in the South Pacific. With a population of 13,649 it is the world's least populous independent republic. Nauru's government operates under its constitution, part two of which contains 'protection of fundamental rights and freedoms.' The Human Rights Council (UNHRC) carried out Nauru's Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in January 2011. The review was generally favourable with only a few areas of concern.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is an international human rights treaty of the United Nations intended to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy full equality under the law. The Convention serves as a major catalyst in the global disability rights movement enabling a shift from viewing persons with disabilities as objects of charity, medical treatment and social protection towards viewing them as full and equal members of society, with human rights. The convention was the first U.N. human rights treaty of the twenty-first century.

The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is a side-agreement to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It was adopted on 13 December 2006, and entered into force at the same time as its parent Convention on 3 May 2008. As of October 2023, it has 94 signatories and 105 state parties.

The Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is an international treaty establishing complaint and inquiry mechanisms for the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 2008, and opened for signature on 24 September 2009. As of October 2023, the Protocol has 46 signatories and 28 state parties. It entered into force on 5 May 2013.

The First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is an international treaty establishing an individual complaint mechanism for the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 16/12/1966, and entered into force on 23/03/1976. As of January 2023, it had 117 state parties and 35 signatories. Two of the ratifying states have denounced the protocol.

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was adopted without a vote by the United Nations General Assembly in the 48/104 resolution of 20 December 1993. Contained within it is the recognition of "the urgent need for the universal application to women of the rights and principles with regard to equality, security, liberty, integrity and dignity of all human beings". It recalls and embodies the same rights and principles as those enshrined in such instruments as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Articles 1 and 2 provide the most widely used definition of violence against women.

The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is a United Nations body of 18 experts that meets two times a year in Geneva to consider the reports submitted by 164 UN member states on their compliance with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and to examine individual petitions concerning 94 States Parties to the Optional Protocol.

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa, has a population of approximately 188,000 people. Samoa gained independence from New Zealand in 1962 and has a Westminster model of Parliamentary democracy which incorporates aspects of traditional practices. In 2016, Samoa ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities CRPD and the three optional protocols to the CRC

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a constitutional parliamentary democracy with an estimated population of 6,187,591. Police brutality, provincial power struggles, violence against women, and government corruption all contribute to the low awareness of basic human rights in the country.

Gender inequality can be found in various areas of Salvadoran life such as employment, health, education, political participation, and family life. Although women in El Salvador enjoy equal protection under the law, they are often at a disadvantage relative to their male counterparts. In the area of politics, women have the same rights as men, but the percentage of women in office compared to men is low. Though much progress has been made since the Salvadoran Civil War ended in 1992, women in El Salvador still face gender inequality.

The Republic of Uruguay is located in South America, between Argentina, Brazil and the South Atlantic Ocean, with a population of 3,332,972. Uruguay gained independence and sovereignty from Spain in 1828 and has full control over its internal and external affairs. From 1973 to 1985 Uruguay was governed by a civil-military dictatorship which committed numerous human rights abuses.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination and the promotion of understanding among all races. The Convention also requires its parties to criminalize hate speech and criminalize membership in racist organizations.

Yoko Hayashi is a Japanese lawyer and partner in the Athena Law Office. She was formerly an alternate member to the United Nations Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights from 2004 to 2006. In 2008, she became a member of the Committee which monitors the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and in 2015 was serving as Chairperson of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Hayashi has used her legal expertise to improve the status and protect the rights of women.

Violence against women in Fiji is recognised to be "pervasive, widespread and a serious national issue" in the Pacific Island region. Fiji's rates of violence against women are "among the very highest in the world". The Fiji Women's Crisis Centre reports that 64% of women who have been in intimate relationships have experienced physical or sexual violence from their partner, including 61% who were physically attacked and 34% who were sexually abused.

Forced marriage is the marriage of one person to another person without the consent of one or both of the parties. It is to be distinguished from an arranged marriage, where the parties do not select their partners but there is free choice to accept or decline the marriage. Forced marriage is widely recognised as a human rights abuse, with some commentators considering it a form of slavery.

Gender equality in Azerbaijan is guaranteed by the country's constitution and legislation, and an initiative is in place to prevent domestic violence. Azerbaijan ratified a United Nations convention in 1995, and a Gender Information Center opened in 2002. A committee on women's issues was established in 1998.

The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, better known as the Belém do Pará Convention, is an international human rights instrument adopted by the Inter-American Commission of Women (CIM) of the Organization of American States (OAS) at a conference held in Belém do Pará, Brazil, on 9 June 1994. It is the first legally binding international treaty that criminalises all forms of violence against women, especially sexual violence. On 26 October 2004, the Follow-Up Mechanism (MESECVI) agency was established to ensure the State parties' compliance with the Convention.