Related Research Articles

Organ donation is the process when a person authorizes an organ of their own to be removed and transplanted to another person, legally, either by consent while the donor is alive, through a legal authorization for deceased donation made prior to death, or for deceased donations through the authorization by the legal next of kin.

Organ transplantation is a medical procedure in which an organ is removed from one body and placed in the body of a recipient, to replace a damaged or missing organ. The donor and recipient may be at the same location, or organs may be transported from a donor site to another location. Organs and/or tissues that are transplanted within the same person's body are called autografts. Transplants that are recently performed between two subjects of the same species are called allografts. Allografts can either be from a living or cadaveric source.

A pancreas transplant is an organ transplant that involves implanting a healthy pancreas into a person who usually has diabetes.

Prior to the introduction of brain death into law in the mid to late 1970s, all organ transplants from cadaveric donors came from non-heart-beating donors (NHBDs).

The Toronto General Hospital (TGH) is a major teaching hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada and the flagship campus of University Health Network (UHN). It is located in the Discovery District of Downtown Toronto along University Avenue's Hospital Row; it is directly north of The Hospital for Sick Children, across Gerrard Street West, and east of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and Mount Sinai Hospital. The hospital serves as a teaching hospital for the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine. In 2019, the hospital was ranked first for research in Canada by Research Infosource for the ninth consecutive year. Since 2020, it has been ranked among the top 5 hospitals in the world by Newsweek.

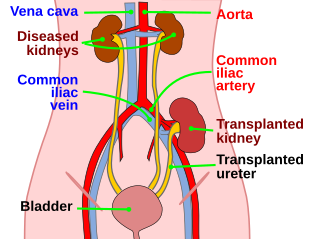

Kidney transplant or renal transplant is the organ transplant of a kidney into a patient with end-stage kidney disease (ESRD). Kidney transplant is typically classified as deceased-donor or living-donor transplantation depending on the source of the donor organ. Living-donor kidney transplants are further characterized as genetically related (living-related) or non-related (living-unrelated) transplants, depending on whether a biological relationship exists between the donor and recipient. The first successful kidney transplant was performed in 1954 by a team including Joseph Murray, the recipient’s surgeon, and Hartwell Harrison, surgeon for the donor. Murray was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990 for this and other work. In 2018, an estimated 95,479 kidney transplants were performed worldwide, 36% of which came from living donors.

Organ procurement is a surgical procedure that removes organs or tissues for reuse, typically for organ transplantation.

Certain fundamental Jewish law questions arise in issues of organ donation. Donation of an organ from a living person to save another's life, where the donor's health will not appreciably suffer, is permitted and encouraged in Jewish law. Donation of an organ from a dead person is equally permitted for the same purpose: to save a life. This simple statement of the issue belies, however, the complexity of defining death in Jewish law. Thus, although there are side issues regarding mutilation of the body etc., the primary issue that prevents organ donation from the dead amongst Jews, in many cases, is the definition of death, simply because to take a life-sustaining organ from a person who was still alive would be murder.

Organ trade is the trading of human organs, tissues, or other body products, usually for transplantation. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), organ trade is a commercial transplantation where there is a profit, or transplantations that occur outside of national medical systems. There is a global need or demand for healthy body parts for transplantation, which exceeds the numbers available.

Transplantable organs and tissues may refer to both organs and tissues that are relatively often transplanted, as well as organs and tissues which are relatively seldom transplanted. In addition to this it may also refer to possible-transplants which are still in the experimental stage.

In December 2006, The UK Government set up the Organ Donation Taskforce to identify barriers to organ donation and recommend actions needed to increase organ donation and procurement within the current legal framework.

Organ transplantation in Israel has historically been low compared to other Western countries due to a common belief that organ donation is prohibited under Jewish law. This changed with the passage of new organ donation laws in 2008. If two patients have the same medical need, priority will now go to the patient who has signed an organ donor card, or whose family members have donated an organ. This policy was nicknamed don't give, don't get. The law also defines "brain death" as an indication of death for all legal purposes, including organ donation. Additionally the law provides financial reimbursement to living donors for medical expenses due to donation and lost time at work. Organ trafficking is explicitly banned. Health insurance plans can no longer reimburse patients who go abroad to receive transplants.

The Ontario Online Donor Registry is a website where Ontario residents, age 16 and older, can register their consent to be an organ and tissue donor. This registry was created to help ease questions and ambiguities with organ donor wishes. The virtual registry also increases Ontario donations with increased accessibility. The registration process can be done through beadonor.ca. Online donor registries have also become popular in the United States, where one can register through Donate Life America; Malaysia, registering through their National Transplant Registry; and Saudi Arabia, registering through the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation.

The Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013 is an act of the National Assembly for Wales, passed in July 2013. It permits an opt-out system of organ donation, known as presumed consent, or deemed consent. The act allows hospitals to presume that people aged 18 or over, who have been resident in Wales for over 12 months, want to donate their organs at their death, unless they have objected specifically. The act varies the Law of England and Wales in Wales, which relied on an opt-in system; whereby only those who have signed the NHS organ donation register, or whose families agreed, were considered to have consented to be organ donors.

MOHAN Foundation is a not-for-profit, registered non-government charity organisation in India that works in the field of deceased organ donation and transplantation. MOHAN is an acronym for Multi Organ Harvesting Aid Network. It has offices in Chennai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai, Chandigarh, Nagpur, Jaipur and information centers at Kerala and Imphal.

BC Transplant Society (BCTS) founded in 1985 is now an agency of Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) in the Canadian province of British Columbia that registers consent to be donors of organs for Organ transplantation.

The Trillium Gift of Life Network was an agency of the Government of Ontario responsible for the province's organ donation strategy, promotion, and supply. Ronnie Gavsie was the President & CEO. The agency maintained the popular BeADonor.ca website. It was subsequently subsumed under Ontario Health in 2019.

The current law in Ireland requires the potential donor to opt in to becoming an organ donor. However, it is ultimately up to their family to make the decision whether or not the person is allowed to donate their organs after they die.

Organ transplantation in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu is regulated by India's Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1994 and is facilitated by the Transplant Authority of Tamil Nadu (TRANSTAN) of the Government of Tamil Nadu and several NGOs. Tamil Nadu ranks first in India in deceased organ donation rate at 1.8 per million population, which is seven times higher than the national average.

Organ donation in India is regulated by the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994. The law allows both deceased and living donors to donate their organs. It also identifies brain death as a form of death. The National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO) functions as the apex body for activities of relating to procurement, allotment and distribution of organs in the country.

References

- 1 2 Wilkinson, K.; Peet, D. (2014). "Organ donation". InnovAiT. 7 (2): 109–116. doi:10.1177/1755738013506565. S2CID 208183197.

- 1 2 "History of organ and tissue donation (2009)". Australian Government Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Organ and tissue donation by living donors, guidelines for ethical practice for health professionals (2007)". Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Organ Donation (2015)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- 1 2 Van Raemdonck, D.E.M., Rega, F.R., Neyrinck, A.P., Jannis, N., Verledenn, G.M., and Lerut, T.E. (2004). "Non heart beating donors". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 16 (4): 309–321. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2004.09.014. PMID 15635535.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Organ Donation". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "Organ and Tissue Donation Frequently Asked Questions". NSW Government Health. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Delriviere, L.; Boronovskis, H. (2011). "Adopting an Opt-Out Registration System for Organ and Tissue Donation in Western Australia". Parliament of Western Australia. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- 1 2 Coppen, R., Friele. R.D., Marquet, R.L. and Gevers, S.K.M. (2005). "Opting-out systems: No guarantee for higher donation rates". Transplant International. 18 (11): 1275–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00202.x . PMID 16221158.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Perry, A.G.; Potter, P.A. (2004). Clinical nursing skills and techniques (5th ed.). St.louis, Missouri: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1254.

- ↑ "Organ and tissue donation policy". Australian Medical Students Association. Retrieved 31 August 2015.[ permanent dead link ]

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oliver, M., Woywodt, A., Ahmed, A., and Saif, I. (2011). "Organ donation, transplantation and religion". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 26 (2): 437–444. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq628 . PMID 20961891.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "2013-2014 Annual Report". Australian Government Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority. 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "Patients Listed for Solid Organ Transplantation Statistics 2013". Australian Government Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority. 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- 1 2 Australian Government Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority (2014). Annual Report.