Model parameters

For the equation of state PSRK needs the critical temperature and pressure, additionally at a minimum the acentric factor for all pure components in the considered mixture is also required.

The integrity of the model can be improved if the acentric factor is replaced by Mathias–Copeman constants fitted to experimental vapor-pressure data of pure components.

The mixing rule uses UNIFAC, which needs a variety of UNIFAC-specific parameters. Aside from some model constants, the most important parameters are the group-interaction parameters — these are obtained from parametric fits to experimental vapor–liquid equilibria of mixtures.

Hence, for high-quality model parameters, experimental data (pure-component vapor pressures and VLE of mixtures) are needed. These are normally provided by factual data banks, like the Dortmund Data Bank, which has been the base for the PSRK development. In few cases additionally needed data have been determined experimentally if no data have been available from other sources.

The latest available parameters have been published in 2005. [3] The further development is now taken over by the UNIFAC Consortium.

In physics and chemistry, an equation of state is a thermodynamic equation relating state variables, which describe the state of matter under a given set of physical conditions, such as pressure, volume, temperature, or internal energy. Most modern equations of state are formulated in the Helmholtz free energy. Equations of state are useful in describing the properties of pure substances and mixtures in liquids, gases, and solid states as well as the state of matter in the interior of stars.

Raoult's law ( law) is a relation of physical chemistry, with implications in thermodynamics. Proposed by French chemist François-Marie Raoult in 1887, it states that the partial pressure of each component of an ideal mixture of liquids is equal to the vapor pressure of the pure component multiplied by its mole fraction in the mixture. In consequence, the relative lowering of vapor pressure of a dilute solution of nonvolatile solute is equal to the mole fraction of solute in the solution.

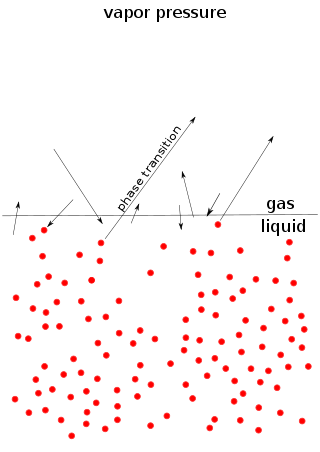

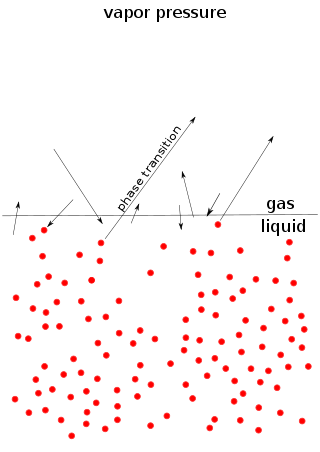

Vapor pressure or equilibrium vapor pressure is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases at a given temperature in a closed system. The equilibrium vapor pressure is an indication of a liquid's thermodynamic tendency to evaporate. It relates to the balance of particles escaping from the liquid in equilibrium with those in a coexisting vapor phase. A substance with a high vapor pressure at normal temperatures is often referred to as volatile. The pressure exhibited by vapor present above a liquid surface is known as vapor pressure. As the temperature of a liquid increases, the attractive interactions between liquid molecules become less significant in comparison to the entropy of those molecules in the gas phase, increasing the vapor pressure. Thus, liquids with strong intermolecular interactions are likely to have smaller vapor pressures, with the reverse true for weaker interactions.

In chemical thermodynamics, activity is a measure of the "effective concentration" of a species in a mixture, in the sense that the species' chemical potential depends on the activity of a real solution in the same way that it would depend on concentration for an ideal solution. The term "activity" in this sense was coined by the American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis in 1907.

The van der Waals equation, named for its originator, the Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, is an equation of state that extends the ideal gas law to include the non-zero size of gas molecules and the interactions between them. As a result the equation is able to model the phase change, liquid vapor. It also produces simple analytic expressions for the properties of real substances that shed light on their behavior. One way to write this equation is:

In physical chemistry, Henry's law is a gas law that states that the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid is directly proportional to its partial pressure above the liquid. The proportionality factor is called Henry's law constant. It was formulated by the English chemist William Henry, who studied the topic in the early 19th century. In simple words, we can say that the partial pressure of a gas in vapour phase is directly proportional to the mole fraction of a gas in solution.

In thermodynamics, an activity coefficient is a factor used to account for deviation of a mixture of chemical substances from ideal behaviour. In an ideal mixture, the microscopic interactions between each pair of chemical species are the same and, as a result, properties of the mixtures can be expressed directly in terms of simple concentrations or partial pressures of the substances present e.g. Raoult's law. Deviations from ideality are accommodated by modifying the concentration by an activity coefficient. Analogously, expressions involving gases can be adjusted for non-ideality by scaling partial pressures by a fugacity coefficient.

In thermodynamics, a critical point is the end point of a phase equilibrium curve. One example is the liquid–vapor critical point, the end point of the pressure–temperature curve that designates conditions under which a liquid and its vapor can coexist. At higher temperatures, the gas cannot be liquefied by pressure alone. At the critical point, defined by a critical temperatureTc and a critical pressurepc, phase boundaries vanish. Other examples include the liquid–liquid critical points in mixtures, and the ferromagnet–paramagnet transition in the absence of an external magnetic field.

The acentric factorω is a conceptual number introduced by Kenneth Pitzer in 1955, proven to be useful in the description of fluids. It has become a standard for the phase characterization of single & pure components, along with other state description parameters such as molecular weight, critical temperature, critical pressure, and critical volume. The acentric factor is also said to be a measure of the non-sphericity (centricity) of molecules.

The Benedict–Webb–Rubin equation (BWR), named after Manson Benedict, G. B. Webb, and L. C. Rubin, is an equation of state used in fluid dynamics. Working at the research laboratory of the M. W. Kellogg Company, the three researchers rearranged the Beattie–Bridgeman equation of state and increased the number of experimentally determined constants to eight.

In thermodynamics and chemical engineering, the vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE) describes the distribution of a chemical species between the vapor phase and a liquid phase.

In statistical thermodynamics, the UNIFAC method is a semi-empirical system for the prediction of non-electrolyte activity in non-ideal mixtures. UNIFAC uses the functional groups present on the molecules that make up the liquid mixture to calculate activity coefficients. By using interactions for each of the functional groups present on the molecules, as well as some binary interaction coefficients, the activity of each of the solutions can be calculated. This information can be used to obtain information on liquid equilibria, which is useful in many thermodynamic calculations, such as chemical reactor design, and distillation calculations.

The non-random two-liquid model is an activity coefficient model introduced by Renon and Prausnitz in 1968 that correlates the activity coefficients of a compound with its mole fractions in the liquid phase concerned. It is frequently applied in the field of chemical engineering to calculate phase equilibria. The concept of NRTL is based on the hypothesis of Wilson, who stated that the local concentration around a molecule in most mixtures is different from the bulk concentration. This difference is due to a difference between the interaction energy of the central molecule with the molecules of its own kind and that with the molecules of the other kind . The energy difference also introduces a non-randomness at the local molecular level. The NRTL model belongs to the so-called local-composition models. Other models of this type are the Wilson model, the UNIQUAC model, and the group contribution model UNIFAC. These local-composition models are not thermodynamically consistent for a one-fluid model for a real mixture due to the assumption that the local composition around molecule i is independent of the local composition around molecule j. This assumption is not true, as was shown by Flemr in 1976. However, they are consistent if a hypothetical two-liquid model is used. Models, which have consistency between bulk and the local molecular concentrations around different types of molecules are COSMO-RS, and COSMOSPACE.

In statistical thermodynamics, UNIQUAC is an activity coefficient model used in description of phase equilibria. The model is a so-called lattice model and has been derived from a first order approximation of interacting molecule surfaces. The model is, however, not fully thermodynamically consistent due to its two-liquid mixture approach. In this approach the local concentration around one central molecule is assumed to be independent from the local composition around another type of molecule.

In physics and thermodynamics, the Redlich–Kwong equation of state is an empirical, algebraic equation that relates temperature, pressure, and volume of gases. It is generally more accurate than the van der Waals equation and the ideal gas equation at temperatures above the critical temperature. It was formulated by Otto Redlich and Joseph Neng Shun Kwong in 1949. It showed that a two-parameter, cubic equation of state could well reflect reality in many situations, standing alongside the much more complicated Beattie–Bridgeman model and Benedict–Webb–Rubin equation that were used at the time. The Redlich–Kwong equation has undergone many revisions and modifications, in order to improve its accuracy in terms of predicting gas-phase properties of more compounds, as well as in better simulating conditions at lower temperatures, including vapor–liquid equilibria.

The UNIFAC Consortium was founded at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg at the chair of industrial chemistry of Prof. Gmehling to invite private companies to support the further development of the group-contribution methods UNIFAC and its successor modified UNIFAC (Dortmund). Both models are used for the prediction of thermodynamic properties, especially the estimation of phase equilibria.

VTPR is an estimation method for the calculation of phase equilibria of mixtures of chemical components. The original goal for the development of this method was to enable the estimation of properties of mixtures which contain supercritical components. These class of substances couldn't be predicted with established models like UNIFAC.

The shear viscosity of a fluid is a material property that describes the friction between internal neighboring fluid surfaces flowing with different fluid velocities. This friction is the effect of (linear) momentum exchange caused by molecules with sufficient energy to move between these fluid sheets due to fluctuations in their motion. The viscosity is not a material constant, but a material property that depends on temperature, pressure, fluid mixture composition, local velocity variations. This functional relationship is described by a mathematical viscosity model called a constitutive equation which is usually far more complex than the defining equation of shear viscosity. One such complicating feature is the relation between the viscosity model for a pure fluid and the model for a fluid mixture which is called mixing rules. When scientists and engineers use new arguments or theories to develop a new viscosity model, instead of improving the reigning model, it may lead to the first model in a new class of models. This article will display one or two representative models for different classes of viscosity models, and these classes are:

Cubic equations of state are a specific class of thermodynamic models for modeling the pressure of a gas as a function of temperature and density and which can be rewritten as a cubic function of the molar volume.

Thermodynamic modelling is a set of different strategies that are used by engineers and scientists to develop models capable of evaluating different thermodynamic properties of a system. At each thermodynamic equilibrium state of a system, the thermodynamic properties of the system are specified. Generally, thermodynamic models are mathematical relations that relate different state properties to each other in order to eliminate the need of measuring all the properties of the system in different states.