Related Research Articles

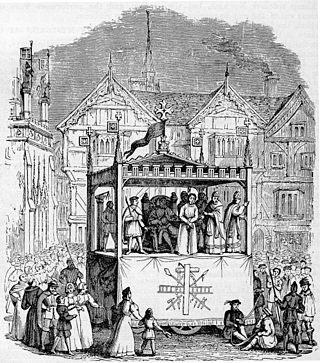

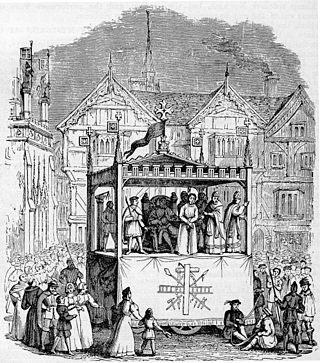

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song. They told of subjects such as the Creation, Adam and Eve, the murder of Abel, and the Last Judgment. Often they were performed together in cycles which could last for days. The name derives from mystery used in its sense of miracle, but an occasionally quoted derivation is from ministerium, meaning craft, and so the 'mysteries' or plays performed by the craft guilds.

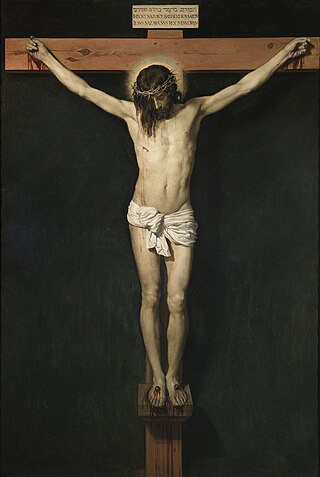

Good Friday is a Christian holy day observing the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Black Friday, Holy Friday, Great Friday, Good Friday of the Passion of the Lord,Great and Holy Friday.

The Passion is the short final period before the death of Jesus, described in the four canonical gospels. It is commemorated in Christianity every year during Holy Week.

Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, among other names, is the day during Holy Week that commemorates the Washing of the Feet (Maundy) and Last Supper of Jesus Christ with the Apostles, as described in the canonical gospels.

The Passion Play or Easter pageant is a dramatic presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus Christ: his trial, suffering and death. The viewing of and participation in Passion Plays is a traditional part of Lent in several Christian denominations, particularly in the Catholic and Evangelical traditions; as such Passion Plays are often ecumenical Christian productions.

Holy Week is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. For all Christian traditions, it is a moveable observance. In Eastern Christianity, which also calls it Great Week, it is the week following Great Lent and Lazarus Saturday, starting on the evening of Palm Sunday and concluding on the evening of Great Saturday. In Western Christianity, Holy Week is the sixth and last week of Lent, beginning with Palm Sunday and concluding on Holy Saturday.

The Oberammergau Passion Play is a passion play that has been performed every 10 years from 1634 to 1674 and each decadal year since 1680 by the inhabitants of the village of Oberammergau, Bavaria, Germany. It was written by Othmar Weis, J A Daisenberger, Otto Huber, Christian Stuckl, Rochus Dedler, Eugen Papst, Marcus Zwink, Ingrid H Shafer, and the inhabitants of Oberammergau, with music by Dedler. Since its first production it has been performed on open-air stages in the village. The text of the play is a composite of four distinct manuscripts dating from the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Chester Mystery Plays is a cycle of mystery plays originating in the city of Chester, England and dating back to at least the early part of the 15th century.

The N-Town Plays are a cycle of 42 medieval Mystery plays from between 1450 and 1500.

Medieval theatre encompasses theatrical in the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and the beginning of the Renaissance in approximately the 15th century. The category of "medieval theatre" is vast, covering dramatic performance in Europe over a thousand-year period. A broad spectrum of genres needs to be considered, including mystery plays, morality plays, farces and masques. The themes were almost always religious. The most famous examples are the English cycle dramas, the York Mystery Plays, the Chester Mystery Plays, the Wakefield Mystery Plays, and the N-Town Plays, as well as the morality play known as Everyman. One of the first surviving secular plays in English is The Interlude of the Student and the Girl.

The York Mystery Plays, more properly the York Corpus Christi Plays, are a Middle English cycle of 48 mystery plays or pageants covering sacred history from the creation to the Last Judgment. They were traditionally presented on the feast day of Corpus Christi and were performed in the city of York, from the mid-fourteenth century until their suppression in 1569. The plays are one of four virtually complete surviving English mystery play cycles, along with the Chester Mystery Plays, the Towneley/Wakefield plays and the N-Town plays. Two long, composite, and late mystery pageants have survived from the Coventry cycle and there are records and fragments from other similar productions that took place elsewhere. A manuscript of the plays, probably dating from between 1463 and 1477, is still intact and stored at the British Library.

Easter is one of the most significant events in the religious and social calendar, celebrated heavily in the European country of Malta.

PLS, or Poculi Ludique Societas, the Medieval & Renaissance Players of Toronto, sponsors productions of early plays, from the beginnings of medieval drama to as late as the middle of the seventeenth century.

Christ Carrying the Cross on his way to his crucifixion is an episode included in the Gospel of John, and a very common subject in art, especially in the fourteen Stations of the Cross, sets of which are now found in almost all Roman Catholic churches, as well as in many Lutheran churches and Anglican churches. However, the subject occurs in many other contexts, including single works and cycles of the Life of Christ or the Passion of Christ. Alternative names include the Procession to Calvary, Road to Calvary and Way to Calvary, Calvary or Golgotha being the site of the crucifixion outside Jerusalem. The actual route taken is defined by tradition as the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, although the specific path of this route has varied over the centuries and continues to be the subject of debate.

A Nativity play or Christmas pageant is a play which recounts the story of the Nativity of Jesus. It is usually performed at Christmas, the feast of the Nativity.

Holy Week is a significant religious observance in the Philippines for the Catholic majority, the Iglesia Filipina Independiente or the Philippine Independent Church, and most Protestant groups. One of the few majority Christian countries in Asia, Catholics make up 78.8 percent of the country's population, and the Church is one of the country's dominant sociopolitical forces.

Scenes from the Passion of Christ is an oil painting on a panel of Baltic oak, painted c.1470 by German-born Early Netherlandish painter Hans Memling. The painting shows 23 vignettes of the Life of Christ combined in one narrative composition without a central dominating scene: 19 episodes from the Passion of Christ, the Resurrection, and three later appearances of the risen Christ. The painting was commissioned by Tommaso Portinari, an Italian banker based in Bruges, who is depicted in a donor portrait kneeling and praying in the lower left corner, with his wife, Maria Baroncelli, in a similar attitude in the lower right corner.

The Preston Passion was a live performance televised by BBC One on 6 April 2012 from Preston, Lancashire, England, retelling the Gospel accounts of the Crucifixion of Jesus through a filter of local history. Organized by the Preston Guild, the performance utilized professional performers, local volunteers and audience members.

Holy Week in Mexico is an important religious observance as well as important vacation period. It is preceded by several observances such as Lent and Carnival, as well as an observance of a day dedicated to the Virgin of the Sorrows, as well as a Mass marking the abandonment of Jesus by the disciples. Holy Week proper begins on Palm Sunday, with the palms used on this day often woven into intricate designs. In many places processions, Masses and other observances can happen all week, but are most common on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday, with just about every community marking the crucifixion of Jesus in some way on Good Friday. Holy Saturday is marked by the Burning of Judas, especially in the center and south of the country, with Easter Sunday usually marked by a Mass as well as the ringing of church bells. Mexico's Holy Week traditions are mostly based on those from Spain, brought over with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, but observances have developed variations in different parts of the country due to the evangelization process in the colonial period and indigenous influences. Several locations have notable observances related to Holy Week including Iztapalapa in Mexico City, Taxco, San Miguel de Allende and San Luis Potosí.

References

- ↑ Muir, Lynette, R (1995). The Biblical Drama of Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rosemary Woolf The English Mystery Plays (Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, 1972)

- ↑ Happé, Peter (1984). Medieval English Drama: A Casebook. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- ↑ Pamela King (2006). The York Mystery Cycle and the Worship of the City. Cambridge: DS Brewer.

- ↑ Ehtstine, Glenn (2012). "'Passion Spectatorship between Private and Public Devotion'". In Elina Gertsman; Jill Stevenson (eds.). Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces. Rochester, NY: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 302–320.

- ↑ Pickering, K. Key Concepts in Drama and Performance (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

- ↑ The York Butchers Gild, The York Butchers Gild - The York Butchers Gild

- ↑ Helen Cooper, Shakespeare and the Medieval World (Bloomsbury: London, 2010).

- ↑ Beadle, Richard and Pamela King. York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- ↑ Dyas, Dee. Images of Faith in English Literature 700-1500: An Introduction (London and New York: Longman, 1997), (p.225).

- ↑ King, Pamela and Clifford Davidson, The Coventry Corpus Christi Plays (Medieval Institute Publications: Western Michigan University Press, 2000).

- ↑ Dyas, Dee. Images of Faith in English Literature 700-1500: An Introduction (London and New York: Longman, 1997), (p.227).

- ↑ 'Fourteenth Century Passion Play', Passion Trust, https://passiontrust.org/fourteenth-passion-play

- ↑ Wenzel, Siegried (1989). ""Somer Game" and Sermon References to a Corpus Christi Play'". Modern Philology. 86 (3): 274–283. doi:10.1086/391705. S2CID 162123003.

- ↑ Cooper, Helen (2010). Shakespeare and the Medieval World. London: Bloomsbury. p. 44.

- ↑ Righter, Anne (1962). Shakespeare and the Idea of the Play. Chatto & Windus.

- ↑ Cooper, Helen (2010). Shakespeare and the Medieval World. London: Bloomsbury.

- ↑ Naseeb Azeez Shaheen, Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays University of Delaware Press, (2011), ISBN 978-1-61149-358-0.

- ↑ "Did Shakespeare watch a Passion Play?". Passion Trust.

- ↑ John D Cox and David Scott Kastan (1997). A New History of Early English Drama John D Cox and David. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Cooper, Helen (2010). Shakespeare and the Medieval World. London: Arden Shakespeare.

- ↑ Muir, Lynette R. (1995). The Biblical Drama of Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Woolf, Rosemary (1972). English Mystery Plays. Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC. p. 312.

- ↑ Brady and Mitchell, Linzy and Jolyon (2016). 'Theatre.' The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and the Arts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Dyas, Dee. Images of Faith in English Literature 700-1500: An Introduction (London and New York: Longman, 1997).

- ↑ John D Cox and David Scott Kastan,'A New History of Early English Drama' (Columbia University Press: NY, 1997).

- ↑ ‘History of Passion Plays’, Passion Plays UK, www.passion-plays.co.uk/

- ↑ 'Press Coverage', Passion Trust, https://www.passion-plays.co.uk/press-coverage/

- ↑ Beadle, Richard and Pamela King. York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- ↑ Margaret Rogerson, York Mystery Plays: Performance in the City (Woodbridge: York, 2011).

- ↑ "Aberdeen Passion Plays". aberdeenpassion.com. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Abingdon Passion Play 2013". Abingdon Blog. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Alresford Passion". passion-plays.co.uk. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Belper Passion 2018" . Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Bewdley Passion 2013". Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Birmingham Passion" . Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ 'Bishop Auckland Easter Story Re-enactment Draws LArge Crowd After Two Year Delay', ITV Tine Tees, https://www.itv.com/news/tyne-tees/2022-04-15/bishop-auckland-easter-story-re-enactment-draws-large-crowd-after-two-year-delay

- ↑ 'Passion Play for Bishop Auckland staged in Market Place', The Northern Echo, 15 April 2022, https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/20072287.passion-play-bishop-auckland-staged-market-place/

- ↑ "About us". soulbythesea.org. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ Vowles, Neil. "Congregations buck trend to prove Christianity is a live and kicking in the 'Godless city'" . Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Carlisle Passion" . Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ 'The Chester Passion 2022', YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BLZ0o6iECM

- ↑ "Theatre Review: The Edinburgh Passion" . Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Great North Passion". BBC One. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Havant Passion Play". havantpassionplay.co.uk. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ ’Behold the Man!’, BBC, BBC Radio Solent - Tim Daykin, Havant Passion Play. Exploring the wardrobe, Behold the Man!

- ↑ "Isle of Man". passion-plays.co.uk. 24 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "DramaKirk". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ "I am with you always". You Tube. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ↑ "Leominster Passion Play". Leominster Passion Play. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Liverpool Passion Play". You Tube. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Parish Church of St Mary Magdalene, Newark-on-Trent" Archived 27 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine , Retrieved 2011-04-12

- ↑ 'Celebrate Norwich and NOrfolk', https://www.networknorwich.co.uk/Articles/634017/Network_Norwich_and_Norfolk/Partners/Celebrate_Norfolk/Celebrate_news/Easter_passion_drama_played_out_on_streets.aspx, accessed 19 April 2022.

- ↑ "Licensing Act 2003".

- ↑ Molloy, Antonia (18 April 2014). "Oxford City Council apologises after Passion Play it 'mistook for live sex show' is cancelled" . Independent.co.uk . Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Poole". Poole Passion Play. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Michael Sheen's Port Talbot Passion Play to be filmed", BBC , 31 January 2011.

- ↑ Passion in Port Talbot/clips "Michael Sheen's Port Talbot Passion Play" clips BBC programmes. Accessed 2015-04-20.

- ↑ Austin, Sue (20 April 2019). "Story of the Crucifixion takes to streets of Shrewsbury". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ T "Southampton passion play brings Easter story to life", BBC , 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "One Life One Passion". One Life One Passion. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Tonbridge". Tonbridge Passion Play. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Trafalgar Square". Wintershall. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ Wintershall Plays Archived 27 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Alpha Beta, March 2015 edition. Monthly publication of the (Roman Catholic) Diocese of Arundel and Brighton, page 10.

- ↑ "Hundreds of people watch Palm Sunday passion play" . Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ "Hundreds of people watch Palm Sunday passion play" . Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ 'Large Crowd Watches Passion Play in Cathedral Square, Worcester News, https://www.worcesternews.co.uk/news/20072441.large-crowd-watches-passion-play-cathedral-square/

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin. "The joy of being part of a Passion play – and a national revival" . Retrieved 30 June 2014.