Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent, was an Italian statesman, the de facto ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lorenzo held the balance of power within the Italic League, an alliance of states that stabilized political conditions on the Italian Peninsula for decades, and his life coincided with the mature phase of the Italian Renaissance and the golden age of Florence. As a patron, he is best known for his sponsorship of artists such as Botticelli and Michelangelo. On the foreign policy front, Lorenzo manifested a clear plan to stem the territorial ambitions of Pope Sixtus IV, in the name of the balance of the Italic League of 1454. For these reasons, Lorenzo was the subject of the Pazzi conspiracy (1478), in which his brother Giuliano was assassinated. The Peace of Lodi of 1454 that he supported among the various Italian states collapsed with his death. He is buried in the Medici Chapel in Florence.

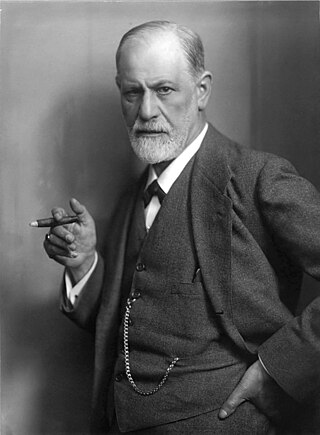

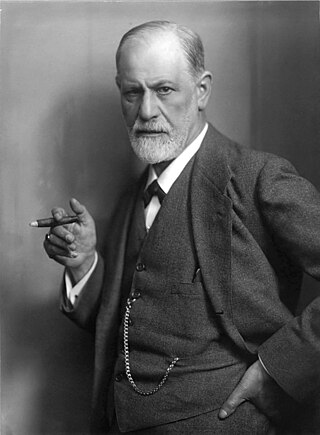

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Carl Gustav Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, psychologist and pioneering evolutionary theorist who founded the school of analytical psychology. He was a prolific author, illustrator, and correspondent, and a complex and controversial character, perhaps best known through his "autobiography" Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

In psychoanalysis and other psychological theories, the unconscious mind is the part of the psyche that is not available to introspection. Although these processes exist beneath the surface of conscious awareness, they are thought to exert an effect on conscious thought processes and behavior. Empirical evidence suggests that unconscious phenomena include repressed feelings and desires, memories, automatic skills, subliminal perceptions, and automatic reactions. The term was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

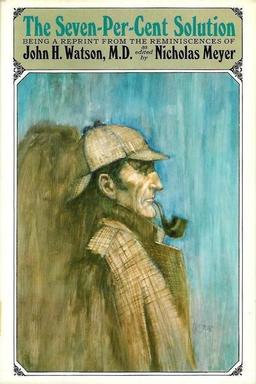

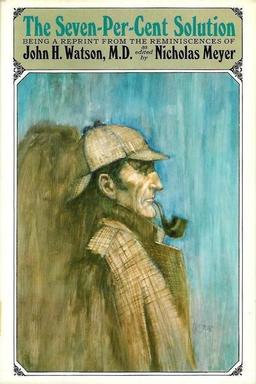

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution: Being a Reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D. is a 1974 novel by American writer Nicholas Meyer. It is written as a pastiche of a Sherlock Holmes adventure, and was made into a film of the same name in 1976.

Peter Joachim Gay was a German-American historian, educator, and author. He was a Sterling Professor of History at Yale University and former director of the New York Public Library's Center for Scholars and Writers (1997–2003). He received the American Historical Association's (AHA) Award for Scholarly Distinction in 2004. He authored over 25 books, including The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, a two-volume award winner; Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (1968); and the widely translated Freud: A Life for Our Time (1988).

Thomas Pearsall Field Hoving was an American museum executive and consultant and the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Leon Levy was an American investor, mutual fund manager, and philanthropist. At his death, Forbes magazine called him “a Wall Street investment genius,” who helped create both mutual funds and hedge funds.

Pierre Marie Félix Janet was a pioneering French psychologist, physician, philosopher, and psychotherapist in the field of dissociation and traumatic memory.

The Euphronios Krater is an ancient Greek terra cotta calyx-krater, a bowl used for mixing wine with water. Created around the year 515 BC, it is the only complete example of the surviving 27 vases painted by the renowned Euphronios and is considered one of the finest Ancient Greek vases in existence.

Psychodynamics, also known as psychodynamic psychology, in its broadest sense, is an approach to psychology that emphasizes systematic study of the psychological forces underlying human behavior, feelings, and emotions and how they might relate to early experience. It is especially interested in the dynamic relations between conscious motivation and unconscious motivation.

Robert Emmanuel Hecht, Jr. was an American antiquities art dealer based in Paris.

In psychology, the psyche is the totality of the human mind, conscious and unconscious. The English word soul is sometimes used synonymously, especially in older texts.

Looted art has been a consequence of looting during war, natural disaster and riot for centuries. Looting of art, archaeology and other cultural property may be an opportunistic criminal act or may be a more organized case of unlawful or unethical pillage by the victor of a conflict. The term "looted art" reflects bias, and whether particular art has been taken legally or illegally is often the subject of conflicting laws and subjective interpretations of governments and people; use of the term "looted art" in reference to a particular art object implies that the art was taken illegally.

Giacomo Medici is an Italian antiquities smuggler and art dealer who was convicted in 2004 of dealing in stolen ancient artifacts. His operation was thought to be "one of the largest and most sophisticated antiquities networks in the world, responsible for illegally digging up and spiriting away thousands of top-drawer pieces and passing them on to the most elite end of the international art market".

Robin Symes was a British antiquities dealer who was unmasked as a key player in an international criminal network that traded in looted archaeological treasures. Symes and his long-term partner Christo Michaelides met and formed a business partnership in the 1970s, and Symes became one of Britain's most prominent and successful antiquities dealers. However, after Michaelides died accidentally in 1999, his family took legal action to recover his share of the Symes company's assets, and when the matter went to trial, Symes was found to have lied in his evidence about the extent and value of his property; he was subsequently charged with and convicted of contempt of court, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment, of which he served seven months. Further investigations by Italian authorities revealed in January 2016 that Symes's involvement in the illegal antiquities trade had been even more extensive than previously thought, and that he had hidden a vast hoard of looted antiquities in 45 crates at the Geneva Freeport storage warehouse in Switzerland for 15 years to conceal them from Michaelides's family.

The Cloisters Cross, is a complex 12th-century ivory Romanesque altar cross or processional cross. It is named after The Cloisters, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which acquired it in 1963.

The archaeological site of Bura is located in the Tillabéry Region, of the Tera Department, in southwest Niger. The Bura archaeological site has given its name to the area's first-millennium Bura culture.

The Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, better known as the Carabinieri T.P.C., is the branch of the Italian Carabinieri responsible for combatting art and antiquities crimes and is viewed as an experienced and efficient task force.

Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint is an 1874 book by the Austrian philosopher Franz Brentano, in which the author argues that the goal of psychology should be to establish exact laws. Brentano's best known book, it established his reputation as a philosopher, helped to establish psychology as a scientific discipline, and influenced Husserlian phenomenology, analytic philosophy, gestalt psychology, and the philosopher Alexius Meinong's theory of objects. It has been called Brentano's best known work and has been compared to the physician Wilhelm Wundt's Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie and the Project for a Scientific Psychology of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis.