Structure

Phosphatidic acid consists of a glycerol backbone, with, in general, a saturated fatty acid bonded to carbon-1, an unsaturated fatty acid bonded to carbon-2, and a phosphate group bonded to carbon-3. [2] [3]

Phosphatidic acids are anionic phospholipids important to cell signaling and direct activation of lipid-gated ion channels. Hydrolysis of phosphatidic acid gives rise to one molecule each of glycerol and phosphoric acid and two molecules of fatty acids. They constitute about 0.25% of phospholipids in the bilayer. [1]

Phosphatidic acid consists of a glycerol backbone, with, in general, a saturated fatty acid bonded to carbon-1, an unsaturated fatty acid bonded to carbon-2, and a phosphate group bonded to carbon-3. [2] [3]

Besides de novo synthesis, PA can be formed in three ways:

The glycerol 3-phosphate pathway for de novo synthesis of PA is shown here:

In addition, PA can be converted into DAG by lipid phosphate phosphohydrolases (LPPs) [6] [7] or into lyso-PA by phospholipase A (PLA).

The role of PA in the cell can be divided into three categories:

The first three roles are not mutually exclusive. For example, PA may be involved in vesicle formation by promoting membrane curvature and by recruiting the proteins to carry out the much more energetically unfavourable task of neck formation and pinching.

PA is a vital cell lipid that acts as a biosynthetic precursor for the formation (directly or indirectly) of all acylglycerol lipids in the cell. [11]

In mammalian and yeast cells, two different pathways are known for the de novo synthesis of PA, the glycerol 3-phosphate pathway or the dihydroxyacetone phosphate pathway. In bacteria, only the former pathway is present, and mutations that block this pathway are lethal, demonstrating the importance of PA. In mammalian and yeast cells, where the enzymes in these pathways are redundant, mutation of any one enzyme is not lethal. However, it is worth noting that in vitro, the various acyltransferases exhibit different substrate specificities with respect to the acyl-CoAs that are incorporated into PA. Different acyltransferases also have different intracellular distributions, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the mitochondria or peroxisomes, and local concentrations of activated fatty acids. This suggests that the various acyltransferases present in mammalian and yeast cells may be responsible for producing different pools of PA. [11]

The conversion of PA into diacylglycerol (DAG) by LPPs is the commitment step for the production of phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylserine (PS). In addition, DAG is also converted into CDP-DAG, which is a precursor for phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and phosphoinositides (PIP, PIP2, PIP3). [11]

PA concentrations are maintained at extremely low levels in the cell by the activity of potent LPPs. [6] These convert PA into DAG very rapidly and, because DAG is the precursor for so many other lipids, it too is soon metabolised into other membrane lipids. This means that any upregulation in PA production can be matched, over time, with a corresponding upregulation in LPPs and in DAG metabolising enzymes.

PA is, therefore, essential for lipid synthesis and cell survival, yet, under normal conditions, is maintained at very low levels in the cell.

PA is a unique phospholipid in that it has a small highly charged head group that is very close to the glycerol backbone. PA is known to play roles in both vesicle fission [12] and fusion, [13] and these roles may relate to the biophysical properties of PA.

At sites of membrane budding or fusion, the membrane becomes or is highly curved. A major event in the budding of vesicles, such as transport carriers from the Golgi, is the creation and subsequent narrowing of the membrane neck. Studies have suggested that this process may be lipid-driven, and have postulated a central role for DAG due to its, likewise, unique molecular shape. The presence of two acyl chains but no headgroup results in a large negative curvature in membranes. [14]

The LPAAT BARS-50 has also been implicated in budding from the Golgi. [12] This suggests that the conversion of lysoPA into PA might affect membrane curvature. LPAAT activity doubles the number of acyl chains, greatly increasing the cross-sectional area of the lipid that lies ‘within’ the membrane while the surface headgroup remains unchanged. This can result in a more negative membrane curvature. Researchers from Utrecht University have looked at the effect of lysoPA versus PA on membrane curvature by measuring the effect these have on the transition temperature of PE from lipid bilayers to nonlamellar phases using 31P-NMR. [15] The curvature induced by these lipids was shown to be dependent not only on the structure of lysoPA versus PA but also on dynamic properties, such as the hydration of head groups and inter- and intramolecular interactions. For instance, Ca2+ may interact with two PAs to form a neutral but highly curved complex. The neutralisation of the otherwise repulsive charges of the headgroups and the absence of any steric hindrance enables strong intermolecular interactions between the acyl chains, resulting in PA-rich microdomains. Thus in vitro, physiological changes in pH, temperature, and cation concentrations have strong effects on the membrane curvature induced by PA and lysoPA. [15] The interconversion of lysoPA, PA, and DAG – and changes in pH and cation concentration – can cause membrane bending and destabilisation, playing a direct role in membrane fission simply by virtue of their biophysical properties. However, though PA and lysoPA have been shown to affect membrane curvature in vitro; their role in vivo is unclear.

The roles of lysoPA, PA, and DAG in promoting membrane curvature do not preclude a role in recruiting proteins to the membrane. For instance, the Ca2+ requirement for the fusion of complex liposomes is not greatly affected by the addition of annexin I, though it is reduced by PLD. However, with annexin I and PLD, the extent of fusion is greatly enhanced, and the Ca2+ requirement is reduced almost 1000-fold to near physiological levels. [13]

Thus the metabolic, biophysical, recruitment, and signaling roles of PA may be interrelated.

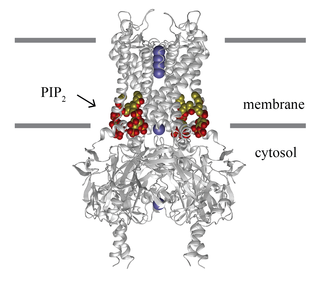

PA is kept low in the bulk of the membrane in order to transiently burst and signal locally in high concentration. [16] For example TREK-1 channels are activated by local association with PLD and production of PA. [17] The dissociation constant of PA for TREK-1 is approximately 10 micromolar. [18] The relatively weak binding combined with a low concentration of PA in the membrane allows the channel to turn off. The local high concentration for activation suggests at least some restrictions in local lipid diffusion. The bulk low concentration of PA combined with high local bursts is the opposite of PIP2 signaling. PIP2 is kept relatively high in the membrane and then transiently hydrolized near a protein in order to transiently reduce PIP2 signaling. [19] PA signaling mirrors PIP2 signaling in that the bulk concentration of signaling lipid need not change to exert a potent local effect on a target protein.

As described above, PLD hydrolyzes PC to form PA and choline. Because choline is very abundant in the cell, PLD activity does not significantly affect choline levels; and choline is unlikely to play any role in signaling.[ citation needed ]

The role of PLD activation in numerous signaling contexts, combined with the lack of a role for choline, suggests that PA is important in signaling. However, PA is rapidly converted to DAG, and DAG is also known to be a signaling molecule. This raises the question as to whether PA has any direct role in signaling or whether it simply acts as a precursor for DAG production. [20] [21] If it is found that PA acts only as a DAG precursor, then one can raise the question as to why cells should produce DAG using two enzymes when they contain the PLC that could produce DAG in a single step.

PA produced by PLD or by DAGK can be distinguished by the addition of [γ-32P]ATP. This will show whether the phosphate group is newly derived from the kinase activity or whether it originates from the PC. [22]

Although PA and DAG are interconvertible, they do not act in the same pathways. Stimuli that activate PLD do not activate enzymes downstream of DAG, and vice versa. For example, it was shown that addition of PLD to membranes results in the production of [32P]-labeled PA and [32P]-labeled phosphoinositides. [23] The addition of DAGK inhibitors eliminates the production of [32P]-labeled PA but not the PLD-stimulated production of phosphoinositides.

It is possible that, though PA and DAG are interconvertible, separate pools of signaling and non-signaling lipids may be maintained. Studies have suggested that DAG signaling is mediated by polyunsaturated DAG, whereas PLD-derived PA is monounsaturated or saturated. Thus functional saturated/monounsaturated PA can be degraded by hydrolysing it to form non-functional saturated/monounsaturated DAG, whereas functional polyunsaturated DAG can be degraded by converting it into non-functional polyunsaturated PA. [20] [24]

This model suggests that PA and DAG effectors should be able to distinguish lipids with the same headgroups but with differing acyl chains. Although some lipid-binding proteins are able to insert themselves into membranes and could hypothetically recognize the type of acyl chain or the resulting properties of the membrane, many lipid-binding proteins are cytosolic and localize to the membrane by binding only the headgroups of lipids. Perhaps the different acyl chains can affect the angle of the head-group in the membrane. If this is the case, it suggests that a PA-binding domain must not only be able to bind PA specifically but must also be able to identify those head-groups that are at the correct angle. Whatever the mechanism is, such specificity is possible. It is seen in the pig testes DAGK that is specific for polyunsaturated DAG [25] and in two rat hepatocyte LPPs that dephosphorylate different PA species with different activities. [26] Moreover, the stimulation of SK1 activity by PS in vitro was shown to vary greatly depending on whether dioleoyl (C18:1), distearoyl (C18:0), or 1-stearoyl, 2-oleoyl species of PS were used. [27] Thus it seems that, though PA and DAG are interconvertible, the different species of lipids can have different biological activities; and this may enable the two lipids to maintain separate signaling pathways.

As PA is rapidly converted to DAG, it is very short-lived in the cell. This means that it is difficult to measure PA production and therefore to study the role of PA in the cell. However, PLD activity can be measured by the addition of primary alcohols to the cell. [28] PLD then carries out a transphosphatidylation reaction, instead of hydrolysis, producing phosphatidyl alcohols in place of PA. The phosphatidyl alcohols are metabolic dead-ends, and can be readily extracted and measured. Thus PLD activity and PA production (if not PA itself) can be measured, and, by blocking the formation of PA, the involvement of PA in cellular processes can be inferred.

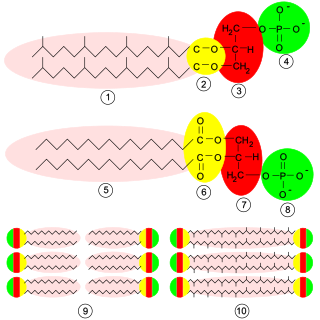

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue. Marine phospholipids typically have omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA integrated as part of the phospholipid molecule. The phosphate group can be modified with simple organic molecules such as choline, ethanolamine or serine.

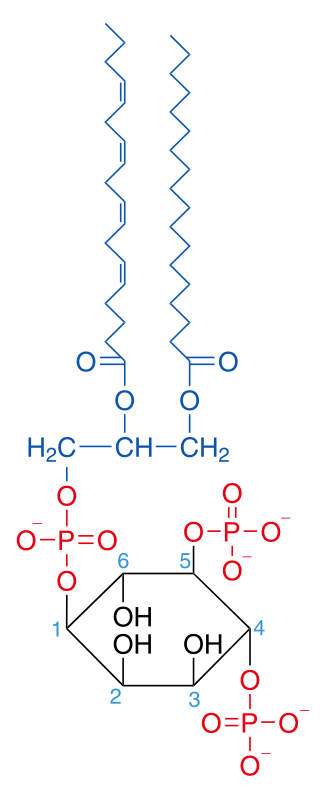

Inositol trisphosphate or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate abbreviated InsP3 or Ins3P or IP3 is an inositol phosphate signaling molecule. It is made by hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid that is located in the plasma membrane, by phospholipase C (PLC). Together with diacylglycerol (DAG), IP3 is a second messenger molecule used in signal transduction in biological cells. While DAG stays inside the membrane, IP3 is soluble and diffuses through the cell, where it binds to its receptor, which is a calcium channel located in the endoplasmic reticulum. When IP3 binds its receptor, calcium is released into the cytosol, thereby activating various calcium regulated intracellular signals.

Phosphatidylcholines (PC) are a class of phospholipids that incorporate choline as a headgroup. They are a major component of biological membranes and can be easily obtained from a variety of readily available sources, such as egg yolk or soybeans, from which they are mechanically or chemically extracted using hexane. They are also a member of the lecithin group of yellow-brownish fatty substances occurring in animal and plant tissues. Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (lecithin) is a major component of the pulmonary surfactant, and is often used in the lecithin–sphingomyelin ratio to calculate fetal lung maturity. While phosphatidylcholines are found in all plant and animal cells, they are absent in the membranes of most bacteria, including Escherichia coli. Purified phosphatidylcholine is produced commercially.

Glycerophospholipids or phosphoglycerides are glycerol-based phospholipids. They are the main component of biological membranes in eukaryotic cells. They are a type of lipid, of which its composition affects membrane structure and properties. Two major classes are known: those for bacteria and eukaryotes and a separate family for archaea.

Phosphoinositide phospholipase C is a family of eukaryotic intracellular enzymes that play an important role in signal transduction processes. These enzymes belong to a larger superfamily of Phospholipase C. Other families of phospholipase C enzymes have been identified in bacteria and trypanosomes. Phospholipases C are phosphodiesterases.

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate or PtdIns(4,5)P2, also known simply as PIP2 or PI(4,5)P2, is a minor phospholipid component of cell membranes. PtdIns(4,5)P2 is enriched at the plasma membrane where it is a substrate for a number of important signaling proteins. PIP2 also forms lipid clusters that sort proteins.

Lipid signaling, broadly defined, refers to any biological cell signaling event involving a lipid messenger that binds a protein target, such as a receptor, kinase or phosphatase, which in turn mediate the effects of these lipids on specific cellular responses. Lipid signaling is thought to be qualitatively different from other classical signaling paradigms because lipids can freely diffuse through membranes. One consequence of this is that lipid messengers cannot be stored in vesicles prior to release and so are often biosynthesized "on demand" at their intended site of action. As such, many lipid signaling molecules cannot circulate freely in solution but, rather, exist bound to special carrier proteins in serum.

Phospholipase D (EC 3.1.4.4, lipophosphodiesterase II, lecithinase D, choline phosphatase, PLD; systematic name phosphatidylcholine phosphatidohydrolase) is an enzyme of the phospholipase superfamily that catalyses the following reaction

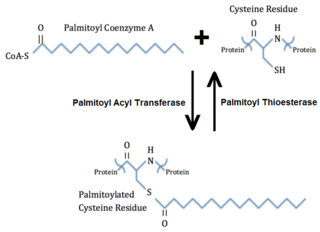

Palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (S-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (O-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typically membrane proteins. The precise function of palmitoylation depends on the particular protein being considered. Palmitoylation enhances the hydrophobicity of proteins and contributes to their membrane association. Palmitoylation also appears to play a significant role in subcellular trafficking of proteins between membrane compartments, as well as in modulating protein–protein interactions. In contrast to prenylation and myristoylation, palmitoylation is usually reversible (because the bond between palmitic acid and protein is often a thioester bond). The reverse reaction in mammalian cells is catalyzed by acyl-protein thioesterases (APTs) in the cytosol and palmitoyl protein thioesterases in lysosomes. Because palmitoylation is a dynamic, post-translational process, it is believed to be employed by the cell to alter the subcellular localization, protein–protein interactions, or binding capacities of a protein.

The lysophospholipid receptor (LPL-R) group are members of the G protein-coupled receptor family of integral membrane proteins that are important for lipid signaling. In humans, there are eleven LPL receptors, each encoded by a separate gene. These LPL receptor genes are also sometimes referred to as "Edg".

Phospholipase D1 (PLD1) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PLD1 gene, though analogues are found in plants, fungi, prokaryotes, and even viruses.

Phospholipase D2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PLD2 gene.

The enzyme phosphatidate phosphatase (PAP, EC 3.1.3.4) is a key regulatory enzyme in lipid metabolism, catalyzing the conversion of phosphatidate to diacylglycerol:

Phospholipase C (PLC) is a class of membrane-associated enzymes that cleave phospholipids just before the phosphate group (see figure). It is most commonly taken to be synonymous with the human forms of this enzyme, which play an important role in eukaryotic cell physiology, in particular signal transduction pathways. Phospholipase C's role in signal transduction is its cleavage of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into diacyl glycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), which serve as second messengers. Activators of each PLC vary, but typically include heterotrimeric G protein subunits, protein tyrosine kinases, small G proteins, Ca2+, and phospholipids.

N-Acylphosphatidylethanolamines (NAPEs) are hormones released by the small intestine into the bloodstream when it processes fat. NAPEs travel to the hypothalamus in the brain and suppress appetite. This mechanism could be relevant for treating obesity.

N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) is an enzyme that catalyzes the release of N-acylethanolamine (NAE) from N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE). This is a major part of the process that converts ordinary lipids into chemical signals like anandamide and oleoylethanolamine. In humans, the NAPE-PLD protein is encoded by the NAPEPLD gene.

2-acyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholines are a class of phospholipids that are intermediates in the metabolism of lipids. Because they result from the hydrolysis of an acyl group from the sn-1 position of phosphatidylcholine, they are also called 1-lysophosphatidylcholine. The synthesis of phosphatidylcholines with specific fatty acids occurs through the synthesis of 1-lysoPC. The formation of various other lipids generates 1-lysoPC as a by-product.

A diglyceride, or diacylglycerol (DAG), is a glyceride consisting of two fatty acid chains covalently bonded to a glycerol molecule through ester linkages. Two possible forms exist, 1,2-diacylglycerols and 1,3-diacylglycerols. Diglycerides are natural components of food fats, though minor in comparison to triglycerides. DAGs can act as surfactants and are commonly used as emulsifiers in processed foods. DAG-enriched oil has been investigated extensively as a fat substitute due to its ability to suppress the accumulation of body fat; with total annual sales of approximately USD 200 million in Japan since its introduction in the late 1990s till 2009.

Lipid-gated ion channels are a class of ion channels whose conductance of ions through the membrane depends directly on lipids. Classically the lipids are membrane resident anionic signaling lipids that bind to the transmembrane domain on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane with properties of a classic ligand. Other classes of lipid-gated channels include the mechanosensitive ion channels that respond to lipid tension, thickness, and hydrophobic mismatch. A lipid ligand differs from a lipid cofactor in that a ligand derives its function by dissociating from the channel while a cofactor typically derives its function by remaining bound.

Substrate presentation is a biological process that activates a protein. The protein is sequestered away from its substrate and then activated by release and exposure of the protein to its substrate. A substrate is typically the substance on which an enzyme acts but can also be a protein surface to which a ligand binds. The substrate is the material acted upon. In the case of an interaction with an enzyme, the protein or organic substrate typically changes chemical form. Substrate presentation differs from allosteric regulation in that the enzyme need not change its conformation to begin catalysis. Substrate presentation is best described for nanoscopic distances (<100 nm).