The Chicago Imagists are a group of representational artists associated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center in the late 1960s.

Barbara Rossi was an American artist, one of the original Chicago Imagists, a group that in the 1960s and 1970s turned to representational art. She first exhibited with them at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1969. She is known for meticulously rendered drawings and cartoonish paintings, as well as a personal vernacular. She worked primarily by making reverse paintings on plexiglass that reference lowbrow and outsider art.

Visual arts of Chicago refers to paintings, prints, illustrations, textile art, sculpture, ceramics and other visual artworks produced in Chicago or by people with a connection to Chicago. Since World War II, Chicago visual art has had a strong individualistic streak, little influenced by outside fashions. "One of the unique characteristics of Chicago," said Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts curator Bob Cozzolino, "is there's always been a very pronounced effort to not be derivative, to not follow the status quo." The Chicago art world has been described as having "a stubborn sense ... of tolerant pluralism." However, Chicago's art scene is "critically neglected." Critic Andrew Patner has said, "Chicago's commitment to figurative painting, dating back to the post-War period, has often put it at odds with New York critics and dealers." It is argued that Chicago art is rarely found in Chicago museums; some of the most remarkable Chicago artworks are found in other cities.

Raymond "Ray" Kakuo Yoshida was an American artist known for his paintings and collages, and for his contributions as a teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1959 to 2005. He was an important mentor of the Chicago Imagists, a group in the 1960s and 1970s who specialized in distorted, emotional representational art.

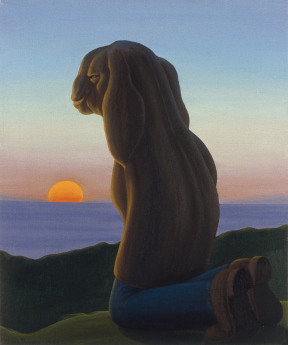

Eleanor Spiess-Ferris is an American symbolist painter cited as a significant surrealist, narrative figurative and feminist artist. Her numerous visual works display powerful influences of the Spanish and Native American cultures of Northern New Mexico, where she grew up. They often reference Penitentes, retablos, Kachinas and Native American fetishes and frequently incorporate themes of feminist spirituality, Indo-European mythology and personal memory.

Christina Ramberg was an American painter associated with the Chicago Imagists, a group of representational artists who attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 1960s. The Imagists took their cues from Surrealism, Pop, and West Coast underground comic illustration, and were "enchanted with the abject status of sex in post-war America, particularly as writ on the female form." Ramberg is best known for her depictions of partial female bodies forced into submission by undergarments and imagined in odd, erotic predicaments.

Richard Wetzel is an American artist. He is best known for his oil paintings but also has exhibited collages and sculpture. In 1969 and 1970, Wetzel exhibited with the Chicago Imagists, a grouping of Chicago artists who were ascendant in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Michiko Itatani is an American artist, based in Chicago, who was born in Osaka, Japan. After she received her BFA (1974) and MFA (1976) at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1974 and 1976 respectively, she returned to her alma mater in 1979 to teach in the Painting and Drawing department. Through her work, Itatani explores identity, continuation, and finding one's way in the modern world. Her work depicts nude figures in an expressionist style. Itatani has received the Illinois Arts Council Artist's Fellowship, the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship. Her work is collected in many museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Olympic Museum, Switzerland; Villa Haiss Museum, Germany; Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Canada; Museu D'art Contemporani (MACBA), Spain; and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, South Korea.

Margaret Wharton (1943-2014) was an American artist, known for her sculptures of deconstructed chairs. She deconstructed, reconstructed and reimagined everyday objects to make works of art that could be whimsical, witty or simply thought-provoking in reflecting her vision of the world.

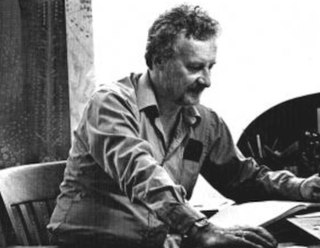

Don Baum was an American curator, artist and educator, most known as a key impresario and promoter of the Chicago Imagists, a group of artists that had an enduring impact on American art in the later twentieth century. Described by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) as "an indispensable curator of the Chicago school," Baum was known for lively and irreverent exhibitions that offered fresh perspectives combining elements of Surrealism and Pop and that broke down barriers between schooled and untrained, or so-called outsider artists. From 1956 to 1972, Baum was exhibitions director at Chicago's Hyde Park Art Center. It was there, in the 1960s, that he became involved with a group of young artists he exhibited as "Hairy Who" that later expanded to become the Chicago Imagists. That group included Ed Paschke, Jim Nutt, Roger Brown, Gladys Nilsson, and Karl Wirsum. Baum mounted two major shows at the MCA that featured the emerging artists in their first museum exhibitions: "Don Baum Sez: 'Chicago Needs Famous Artists'" (1969) and "Made in Chicago" (1973), which shaped a vision of Chicago's art world as a place of meticulous craftsmanship and vernacular inspiration.

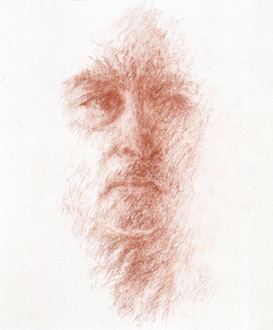

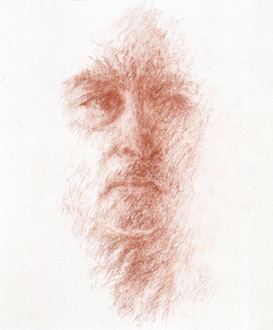

Arthur Lerner is an American artist, known for his atmospheric figurative paintings and drawings, landscapes, and still lifes. He is sometimes described as a realist, but most critics observe that his work is more subjective than descriptive or literal. Associated with Chicago's influential "Monster Roster" artists early in his career, he shared their enthusiasm for expressive figuration, fantasy and mythology, and their existential outlook, but diverged increasingly in his classical formal concerns and more detached temperament. Critics frequently note in Lerner's art a sense of light that evokes Impressionism, delicate color and modelling that "flirts with dematerialization," and the draftsmanship that serves as a foundation for all of his work. The Chicago Tribune's Alan Artner lamented Lerner's comparative lack of recognition in relation to the Chicago Imagists as the fate of "an aesthete in a town dominated by tenpenny fantasts." Lerner's work has been extensively covered in publications, featured in books such as Monster Roster: Existential Art in Postwar Chicago, and acquired by public and private collections, including those of the Smithsonian Institution, Art Institute of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art, and Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, among many.

Jan Cicero Gallery was a contemporary art gallery founded and directed by Jan Cicero, which operated from 1974 to 2003, with locations in Evanston and Chicago, Illinois and Telluride, Colorado. The gallery was noted for its early, exclusive focus on Chicago abstract artists at a time when they were largely neglected, its role in introducing Native American artists to mainstream art venues beyond the Southwest, and its showcasing of late-career and young women artists. The gallery focused on painting, and to a lesser degree, works on paper, often running counter to the city's prevailing art currents. It was also notable as a pioneer of two burgeoning Chicago gallery districts, the West Hubbard Street alternative corridor of the 1970s, and the River North district in the 1980s.

David Sharpe is an American artist, known for his stylized and expressionist paintings of the figure and landscape and for early works of densely packed, organic abstraction. He was trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and worked in Chicago until 1970, when he moved to New York City, where he remains. Sharpe has exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), The Drawing Center, Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art, and Chicago Cultural Center, among many venues. His work has been reviewed in Art in America, ARTnews, Arts Magazine, New Art Examiner, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune, and been acquired by public institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, MCA Chicago, Smart Museum of Art, and Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, among many.

Paul Christopher Lamantia is an American visual artist, known for paintings and drawings that explore dark psychosexual imagery. He studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as part of the larger group of artists known as the Chicago Imagists.

Robert Morris Donley is an American artist who has been identified with the Chicago Imagist movement. Judith Wilson of the Village Voice called him the "Chicago imagist Tolstoy." The narrative aspects of his work center on broad social and political statements that are complex--often playful and satirical with respect to ways in which propaganda, power, and social diversity mix with and conflict with historical and religious personalities. In his career retrospective in 2000 at the Chicago Cultural Center, Dr. Paul Jaskot wrote that "his art investigates the changing political and social geographies of [the modern] city."

Laurie Hogin is an American artist, known for allegorical paintings of mutant animals and plants that rework the tropes and exacting styles of Neoclassical art in order to critique, parody or call attention to contemporary and historical mythologies, systems of power, and human experience and variety. She has exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, International Print Center New York, and Contemporary Arts Center Cincinnati. Her work belongs to the art collections of the New York Public Library, MacArthur Foundation, Addison Gallery of American Art, and Illinois State Museum, among others. Critic Donald Kuspit described her work as both painted with "a deceptive, crafty beauty" and "sardonically aggressive" in its use of animal stand-ins to critique humanity; Ann Wiens characterized her "roiling compositions of barely controlled flora and fauna" as "shrewdly employing art historical concepts of beauty for their subversive potential." Hogin is Professor and Chair of the Studio Art Program at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

Frank Piatek is an American artist, known for abstract, illusionistic paintings of tubular forms and three-dimensional works exploring spirituality, cultural memory and the creative process. Piatek emerged in the mid-1960s, among a group of Chicago artists exploring various types of organic abstraction that shared qualities with the Chicago Imagists; his work, however relies more on suggestion than expressionistic representation. In Art in Chicago 1945-1995, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) described Piatek as playing “a crucial role in the development and refinement of abstract painting in Chicago" with carefully rendered, biomorphic compositions that illustrate the dialectical relationship between Chicago's idiosyncratic abstract and figurative styles. Piatek's work has been exhibited at institutions including the Whitney Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, MCA Chicago, National Museum, Szczecin in Poland, and Terra Museum of American Art; it belongs to the public art collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and MCA Chicago, among others. Curator Lynne Warren describes Piatek as "the quintessential Chicago artist—a highly individualistic, introspective outsider" who has developed a "unique and deeply felt world view from an artistically isolated vantage point." Piatek lives and works in Chicago with his wife, painter and SAIC professor Judith Geichman, and has taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago since 1974.

Richard Loving (1924–2021) was an American artist and educator, primarily based in Chicago, Illinois. He gained recognition in the 1980s as a member of the "Allusive Abstractionists," an informal group of Chicago painters, whose individual forms of organic abstraction embraced evocative imagery and metaphor, counter to the dominant minimalist mode. He is most known for paintings that critics describe as metaphysical and visionary, which move fluidly between abstraction and representation, personalized symbolism taking organic and geometric forms, and chaos and order. They are often characterized by bright patterns of dotted lines and dashes, enigmatic spatial fields, and an illuminated quality. In 2010, critic James Yood wrote that Loving's work "mull[ed] over the possibilities of pattern and representation, of narrative and allegory" to attain a kind of wisdom, transcendence and acknowledgement of universals, "seeking understanding of self within the poetics of the physical world."

Lynne Warren an American curator and writer who worked from 1977 to 2020 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago. She is a scholar of the Chicago Imagists, conceptual photography, Alexander Calder, and Chicago art from the mid-twenty-first century to the present. Sixty Inches from Center called her a "true pioneer in the field of contemporary art" in 2017.

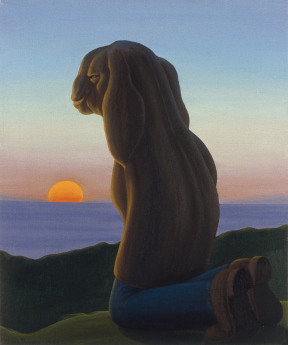

Tony Phillips is an American artist and educator based in Chicago whose work has included painting, drawing and film. He is associated with figurative and surrealist currents of Chicago art in the later 20th century, without precisely being identified with such groups as the Imagists or The Hairy Who; critics have suggested that the lack of such affiliations has caused him and similar artists in the city to be comparatively overlooked. His art employs painterly, softly modeled representation that belies sometimes dark psychological explorations and fantastical or archetypal scenarios. Art in America critic Robert Berlind wrote, "Phillips's best pictures, with their particular tension between humor and eeriness, between the familiar and the eccentric, between the fanciful and the obsessive, are like a high-wire act, carried off in dream time."