In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas was a Trojan hero, the son of the Dardanian prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite. His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy, making Aeneas a second cousin to Priam's children. He is a minor character in Greek mythology and is mentioned in Homer's Iliad. Aeneas receives full treatment in Roman mythology, most extensively in Virgil's Aeneid, where he is cast as an ancestor of Romulus and Remus. He became the first true hero of Rome. Snorri Sturluson identifies him with the Norse god Vidarr of the Æsir.

Publius Vergilius Maro, usually called Virgil or Vergil in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the Eclogues, the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid. A number of minor poems, collected in the Appendix Vergiliana, were attributed to him in ancient times, but modern scholars consider his authorship of these poems as dubious.

The Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It comprises 9,896 lines in dactylic hexameter. The first six of the poem's twelve books tell the story of Aeneas' wanderings from Troy to Italy, and the poem's second half tells of the Trojans' ultimately victorious war upon the Latins, under whose name Aeneas and his Trojan followers are destined to be subsumed.

The tale of the founding of Rome is recounted in traditional stories handed down by the ancient Romans themselves as the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, twins who were suckled by a she-wolf as infants. Another account, set earlier in time, claims that the Roman people are descended from Trojan War hero Aeneas, who escaped to Italy after the war, and whose son, Iulus, was the ancestor of the family of Julius Caesar. The archaeological evidence of human occupation of the area of modern-day Rome dates from about 14,000 years ago.

Ascanius was a legendary king of Alba Longa and is the son of the Trojan hero Aeneas and Creusa, daughter of Priam. He is a character in Roman mythology, and has a divine lineage, being the son of Aeneas, who is the son of the goddess Venus and the hero Anchises, a relative of the king Priam; thus Ascanius has divine ascendents by both parents, being descendants of god Jupiter and Dardanus. He is also an ancestor of Romulus, Remus and the Gens Julia. Together with his father, he is a major character in Virgil's Aeneid, and he is depicted as one of the founders of the Roman race.

Anchises was a member of the royal family of Troy in Greek and Roman legend. He was said to have been the son of King Capys of Dardania and Themiste, daughter of Ilus, who was son of Tros. He is most famous as the father of Aeneas and for his treatment in Virgil's Aeneid. Anchises' brother was Acoetes, father of the priest Laocoön.

In Roman mythology, the Aeneads were the friends, family and companions of Aeneas, with whom they fled from Troy after the Trojan War. Aenides was another patronymic from Aeneas, which is applied by Gaius Valerius Flaccus to the inhabitants of Cyzicus, whose town was believed to have been founded by Cyzicus, the son of Aeneas and Aenete. Similarly, Aeneades was a patronymic from Aeneas, and applied as a surname to those who were believed to have been descended from him, such as Ascanius, Augustus, and the Romans in general.

Brutus, also called Brute of Troy, is a legendary descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, known in medieval British legend as the eponymous founder and first king of Britain. This legend first appears in the Historia Brittonum, an anonymous 9th-century historical compilation to which commentary was added by Nennius, but is best known from the account given by the 12th-century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae.

The Dardanoi were a legendary people of the Troad, located in northwestern Anatolia. The Dardanoi were the descendants of Dardanus, the mythical founder of Dardanus, an ancient city in the Troad. A contingent of Dardanians figures among Troy's allies in the Trojan War. Homer makes a clear distinction between the Trojans and the Dardanoi, however, "Dardanoi"/"Dardanian" later became essentially metonymous–– or at least is commonly perceived to be so–– with "Trojan", especially in the works of Vergil such as the Aeneid.

Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius is a sculpture by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini created c. 1618-19. Housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the sculpture depicts a scene from the Aeneid, where the hero Aeneas leads his family from burning Troy.

The kings of Alba Longa, or Alban kings, were a series of legendary kings of Latium, who ruled from the ancient city of Alba Longa. In the mythic tradition of ancient Rome, they fill the 400-year gap between the settlement of Aeneas in Italy and the founding of the city of Rome by Romulus. It was this line of descent to which the Julii claimed kinship. The traditional line of the Alban kings ends with Numitor, the grandfather of Romulus and Remus. One later king, Gaius Cluilius, is mentioned by Roman historians, although his relation to the original line, if any, is unknown; and after his death, a few generations after the time of Romulus, the city was destroyed by Tullus Hostilius, the third King of Rome, and its population transferred to Alba's daughter city.

In Greek and Roman mythology, Nisus and Euryalus are a pair of friends and lovers serving under Aeneas in the Aeneid, the Augustan epic by Virgil. Their foray among the enemy, narrated in book nine, demonstrates their stealth and prowess as warriors, but ends as a tragedy: the loot Euryalus acquires attracts attention, and the two die together. Virgil presents their deaths as a loss of admirable loyalty and valor. They also appear in Book 5, during the funeral games of Anchises, where Virgil takes note of their amor pius, a love that exhibits the pietas that is Aeneas's own distinguishing virtue.

Lavinia is the Locus Award-winning novel by American author Ursula K. Le Guin. Published in 2008, it was Le Guin's last novel. It is written in a first-person, self-conscious style that recounts the life of Lavinia, a minor character in Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid.

Alba Longa was an ancient Latin city in Central Italy in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. The ancient Romans believed it to be the founder and head of the Latin League, before it was destroyed by the Roman Kingdom around the middle of the 7th century BC and its inhabitants were forced to settle in Rome. In legend, Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome, had come from the royal dynasty of Alba Longa, which in Virgil's Aeneid had been the bloodline of Aeneas, a son of Venus.

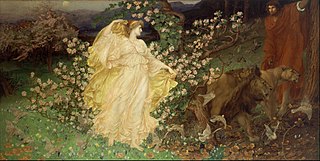

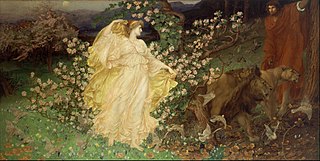

The Golden Bough is one of the episodic tales written in the epic Aeneid, book VI, by the Roman poet Virgil, which narrates the adventures of the Trojan hero Aeneas after the Trojan War.

When writing the Aeneid, Virgil drew from his studies on the Homeric epics of the Iliad to help him create a national epic poem for the Roman people. Virgil used several characteristics associated with epic poetry, more specifically Homer's epics, including the use of hexameter verse, book division, lists of genealogies and underlying themes to draw parallels between the Romans and their cultural predecessors, the Greeks.

In Greek mythology, Creusa was the daughter of Priam and Hecuba. She was the first wife of Aeneas and mother to Ascanius.

Eneide is a seven-episode 1971–1972 Italian television drama, adapted by Franco Rossi from Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid. It stars Giulio Brogi as Aeneas and Olga Karlatos as Dido, and also stars Alessandro Haber, Andrea Giordana and Marilù Tolo. RAI originally broadcast the hour-long episodes from 19 December 1971 to 30 January 1972. A shorter theatrical version was released in 1974 as Le avventure di Enea.

The Shield of Aeneas is the shield that Aeneas receives from the god Vulcan in Book VIII of Virgil's Aeneid to aid in his war against the Rutuli. Imprinted on the front of the shield is a grand depiction of the destiny of Aeneas' descendants and the future of Rome.