Inorganic chemistry deals with synthesis and behavior of inorganic and organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subjects of organic chemistry. The distinction between the two disciplines is far from absolute, as there is much overlap in the subdiscipline of organometallic chemistry. It has applications in every aspect of the chemical industry, including catalysis, materials science, pigments, surfactants, coatings, medications, fuels, and agriculture.

Organic chemistry is a branch of chemistry that studies the structure, properties and reactions of organic compounds, which contain carbon-carbon covalent bonds. Study of structure determines their structural formula. Study of properties includes physical and chemical properties, and evaluation of chemical reactivity to understand their behavior. The study of organic reactions includes the chemical synthesis of natural products, drugs, and polymers, and study of individual organic molecules in the laboratory and via theoretical study.

In polymer science, the polymer chain or simply backbone of a polymer is the main chain of a polymer. Polymers are often classified according to the elements in the main chains. The character of the backbone, i.e. its flexibility, determines the properties of the polymer. For example, in polysiloxanes (silicone), the backbone chain is very flexible, which results in a very low glass transition temperature of −123 °C. The polymers with rigid backbones are prone to crystallization in thin films and in solution. Crystallization in its turn affects the optical properties of the polymers, its optical band gap and electronic levels.

In chemistry, catenation is the bonding of atoms of the same element into a series, called a chain. A chain or a ring shape may be open if its ends are not bonded to each other, or closed if they are bonded in a ring. The words to catenate and catenation reflect the Latin root catena, "chain".

Conductive polymers or, more precisely, intrinsically conducting polymers (ICPs) are organic polymers that conduct electricity. Such compounds may have metallic conductivity or can be semiconductors. The biggest advantage of conductive polymers is their processability, mainly by dispersion. Conductive polymers are generally not thermoplastics, i.e., they are not thermoformable. But, like insulating polymers, they are organic materials. They can offer high electrical conductivity but do not show similar mechanical properties to other commercially available polymers. The electrical properties can be fine-tuned using the methods of organic synthesis and by advanced dispersion techniques.

![<span class="mw-page-title-main">Polyacetylene</span> Organic polymer made of the repeating unit [C2H2]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Cis-and-trans-polyacetylene-chains-symmetric-8-based-on-xtals-3D-bs-17.png/320px-Cis-and-trans-polyacetylene-chains-symmetric-8-based-on-xtals-3D-bs-17.png)

Polyacetylene usually refers to an organic polymer with the repeating unit [C2H2]n. The name refers to its conceptual construction from polymerization of acetylene to give a chain with repeating olefin groups. This compound is conceptually important, as the discovery of polyacetylene and its high conductivity upon doping helped to launch the field of organic conductive polymers. The high electrical conductivity discovered by Hideki Shirakawa, Alan Heeger, and Alan MacDiarmid for this polymer led to intense interest in the use of organic compounds in microelectronics. This discovery was recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000. Early work in the field of polyacetylene research was aimed at using doped polymers as easily processable and lightweight "plastic metals". Despite the promise of this polymer in the field of conductive polymers, many of its properties such as instability to air and difficulty with processing have led to avoidance in commercial applications.

Polythiophenes (PTs) are polymerized thiophenes, a sulfur heterocycle. The parent PT is an insoluble colored solid with the formula (C4H2S)n. The rings are linked through the 2- and 5-positions. Poly(alkylthiophene)s have alkyl substituents at the 3- or 4-position(s). They are also colored solids, but tend to be soluble in organic solvents.

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), also known as dimethylpolysiloxane or dimethicone, belongs to a group of polymeric organosilicon compounds that are commonly referred to as silicones. PDMS is the most widely used silicon-based organic polymer, as its versatility and properties lead to many applications.

Polysulfides are a class of chemical compounds containing chains of sulfur atoms. There are two main classes of polysulfides: inorganic and organic. Among the inorganic polysulfides, there are ones which contain anions, which have the general formula S2−

n. These anions are the conjugate bases of the hydrogen polysulfides H2Sn. Organic polysulfides generally have the formulae R1SnR2, where R = alkyl or aryl.

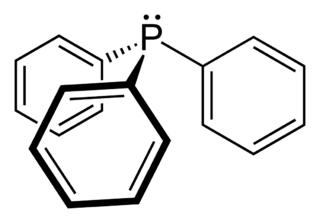

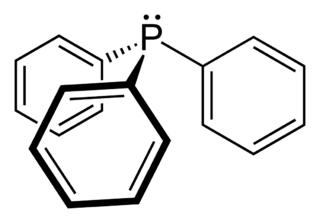

Triphenylphosphine (IUPAC name: triphenylphosphane) is a common organophosphorus compound with the formula P(C6H5)3 and often abbreviated to PPh3 or Ph3P. It is widely used in the synthesis of organic and organometallic compounds. PPh3 exists as relatively air stable, colorless crystals at room temperature. It dissolves in non-polar organic solvents such as benzene and diethyl ether.

Palladium(II) acetate is a chemical compound of palladium described by the formula [Pd(O2CCH3)2]n, abbreviated [Pd(OAc)2]n. It is more reactive than the analogous platinum compound. Depending on the value of n, the compound is soluble in many organic solvents and is commonly used as a catalyst for organic reactions.

Polyphosphazenes include a wide range of hybrid inorganic-organic polymers with a number of different skeletal architectures with the backbone P-N-P-N-P-N-. In nearly all of these materials two organic side groups are attached to each phosphorus center. Linear polymers have the formula (N=PR1R2)n, where R1 and R2 are organic (see graphic). Other architectures are cyclolinear and cyclomatrix polymers in which small phosphazene rings are connected together by organic chain units. Other architectures are available, such as block copolymer, star, dendritic, or comb-type structures. More than 700 different polyphosphazenes are known, with different side groups (R) and different molecular architectures. Many of these polymers were first synthesized and studied in the research group of Harry R. Allcock.

Hexachlorophosphazene is an inorganic compound with the formula (NPCl2)3. The molecule has a cyclic, unsaturated backbone consisting of alternating phosphorus and nitrogen centers, and can be viewed as a trimer of the hypothetical compound N≡PCl2. Its classification as a phosphazene highlights its relationship to benzene. There is large academic interest in the compound relating to the phosphorus-nitrogen bonding and phosphorus reactivity.

An inorganic polymer is a polymer with a skeletal structure that does not include carbon atoms in the backbone. Polymers containing inorganic and organic components are sometimes called hybrid polymers, and most so-called inorganic polymers are hybrid polymers. One of the best known examples is polydimethylsiloxane, otherwise known commonly as silicone rubber. Inorganic polymers offer some properties not found in organic materials including low-temperature flexibility, electrical conductivity, and nonflammability. The term inorganic polymer refers generally to one-dimensional polymers, rather than to heavily crosslinked materials such as silicate minerals. Inorganic polymers with tunable or responsive properties are sometimes called smart inorganic polymers. A special class of inorganic polymers are geopolymers, which may be anthropogenic or naturally occurring.

Carbon diselenide is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula CSe2. It is a yellow-orange oily liquid with pungent odor. It is the selenium analogue of carbon disulfide (CS2). This light-sensitive compound is insoluble in water and soluble in organic solvents.

Harry R. Allcock is Evan Pugh Professor of chemistry at Pennsylvania State University.

A high-refractive-index polymer (HRIP) is a polymer that has a refractive index greater than 1.50.

Polysilazanes are polymers in which silicon and nitrogen atoms alternate to form the basic backbone. Since each silicon atom is bound to two separate nitrogen atoms and each nitrogen atom to two silicon atoms, both chains and rings of the formula occur. can be hydrogen atoms or organic substituents. If all substituents R are H atoms, the polymer is designated as Perhydropolysilazane, Polyperhydridosilazane, or Inorganic Polysilazane ([H2Si–NH]n). If hydrocarbon substituents are bound to the silicon atoms, the polymers are designated as Organopolysilazanes. Molecularly, polysilazanes are isoelectronic with and close relatives to Polysiloxanes (silicones).

Polysilanes are organosilicon compounds with the formula (R2Si)n. They are relatives of traditional organic polymers but their backbones are composed of silicon atoms. They exhibit distinctive optical and electrical properties. They are mainly used industrially as precursors to silicon carbide. The simplest polysilane would be (SiH2)n, which is mainly of theoretical, not practical interest.

Smart inorganic polymers (SIPs) are hybrid or fully inorganic polymers with tunable (smart) properties such as stimuli responsive physical properties. While organic polymers are often petrol-based, the backbones of SIPs are made from elements other than carbon which can lessen the burden on scarce non-renewable resources and provide more sustainable alternatives. Common backbones utilized in SIPs include polysiloxanes, polyphosphates, and polyphosphazenes, to name a few.

![<span class="mw-page-title-main">Polyacetylene</span> Organic polymer made of the repeating unit [C2H2]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Cis-and-trans-polyacetylene-chains-symmetric-8-based-on-xtals-3D-bs-17.png/320px-Cis-and-trans-polyacetylene-chains-symmetric-8-based-on-xtals-3D-bs-17.png)