Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, medicine and material culture. Chinese Buddhism is the largest institutionalized religion in Mainland China. Currently, there are an estimated 185 to 250 million Chinese Buddhists in the People's Republic of China. It is also a major religion in Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia, as well as among the Chinese Diaspora.

New Confucianism is an intellectual movement of Confucianism that began in the early 20th century in Republican China, and further developed in post-Mao era contemporary China. It primarily developed during the May Fourth Movement. It is deeply influenced by, but not identical with, the neo-Confucianism of the Song and Ming dynasties.

Sinology, or Chinese studies, is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of China primarily through Chinese philosophy, language, literature, culture and history and often refers to Western scholarship. Its origin "may be traced to the examination which Chinese scholars made of their own civilization."

In Chinese philosophy, the three teachings are Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, considered as a harmonious aggregate. Literary references to the "three teachings" by prominent Chinese scholars date back to the 6th century. The term may also refer to a non-religious philosophy built on that aggregation.

Buddhism has interacted with several Eastern religions such as Taoism, Shinto and Bon since it spread from the Indian subcontinent during the 2nd century AD.

Chen Cheng (1365–1457), courtesy name Zilu (子鲁), pseudonym Zhushan (竹山), was a Chinese diplomat known for his overland journeys into Central Asia during the Ming dynasty. His travels were contemporaneous to the treasure voyages of the admiral Zheng He.

Homer Hasenpflug Dubs was an American sinologist and polymath. Though best known for his translation of sections of Ban Gu's Book of Han, he published on a wide range of topics in ancient Chinese history, astronomy and philosophy. Raised in China as the son of missionaries, he returned to the United States and earned a Ph.D. in philosophy (1925). He taught at University of Minnesota and Marshall College before undertaking the Han shu translation project at the behest of the American Council of Learned Societies. Subsequently, Dubs taught at Duke University, Columbia University and Hartford Seminary. In 1947, Dubs moved to England to take up the Chair of Chinese at Oxford University, which had been vacant since 1935. He retired in 1959 and remained in Oxford until his death in 1969.

Parâkramabâhu VI was the first king of Kotte, ruling from 1410 until his death in 1467. He is the last great king in Sri Lanka who managed to unite the island under one flag. His rule is famous for the renaissance in Sinhalese literature, due to the patronage of the king himself. Classical literature as well as many rock inscriptions and royal grant letters have been found, rendering much information pertaining to this period.

Timothy James Brook is a Canadian historian, sinologist, and writer specializing in the study of China (sinology). He holds the Republic of China Chair, Department of History, University of British Columbia.

The Chinese State in Ming Society is a history book which investigates the role of the state in China in the Ming dynasty ; the interface between the state and society, and the effect of the state on ordinary people.

Erik Zürcher was a Dutch Sinologist. From 1962 to 1993, Zürcher was a professor of history of East Asia at the Leiden University. He was also Director of the Sinological Institute, between 1975 and 1990. His Chinese name was Xǔ Lǐhe (许理和).

Henri Cordier was a French linguist, historian, ethnographer, author, editor and Orientalist. He was President of the Société de Géographie in Paris. Cordier was a prominent figure in the development of East Asian and Central Asian scholarship in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. Though he had little actual knowledge of the Chinese language, Cordier had a particularly strong impact on the development of Chinese scholarship, and was a mentor of the noted French sinologist Édouard Chavannes.

Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak was a Dutch Sinologist and professor of Chinese at Leiden University. He is known for his translation of The Book of Lord Shang and his studies of the Dao De Jing. He was co-editor of the renowned sinology journal T'oung Pao with French scholar Paul Pelliot for several decades.

The Southern Shaolin Monastery or Nan-Shaolin (南少林) is the name of a Buddhist monastery whose existence and location are both disputed although associated ruins have been identified. By tradition, it is considered a source of Nanquan.

Paul Demiéville was a Swiss-French sinologist and Orientalist known for his studies of the Dunhuang manuscripts and Buddhism and his translations of Chinese poetry, as well as for his 30-year tenure as co-editor of T'oung Pao.

Stephen F. Teiser is the D. T. Suzuki Professor in Buddhist Studies and Professor of Religion at Princeton University, where he is also the Director of the Program in East Asian Studies. His scholarship is known for a broad conception of Buddhist thinking and practice, showing the interactions between Buddhism in India, China, Korea and Japan, especially in the medieval period; for the use of wide-ranging sources, not only texts and documents, but artistic and material; for a theoretical approach that builds insights from history, anthropology, literary theory, and religious studies; and for seeing Buddhism in both elite and popular contexts.

Holy Emperor Guan's True Scripture to Awaken the World (關聖帝君覺世真經) is a Taoist classic, believed to be written by Lord Guan himself during a Fuji session in 1668. Its name is usually shortened to Scripture to Awaken the World. The purpose of this scripture is to advise people against committing evil deeds for fear of retribution. It is classified as one of the three Taoist Holy Scriptures for Advising the Good, the other two being Lao‑Tzu's Treatise On the Response of the Tao and Lord Superior Wen Chang Tract of the Quiet Way.

Shamanism in China can be traced back to the early Shang Dynasty. During the Shang Dynasty, it was common for shamans to hold positions as low ranking state officials, often serving as spirit mediums, fortune-tellers, healers, and exorcists. Shamanism continued to proliferate throughout China until the Sui Dynasty, when Confucianism and Daoism began to take over religious thought and tradition. Daoists saw shamans as a threat since they were often employed to perform similar rituals and exorcisms. Eventually Shamanism declined drastically in the Song dynasty once Daoism became more influential in the Song China's courts. Daoist traditions and rituals gained influence and shamans were seen as false healers who exploited their clients for financial gain. Over time shaman healers, who were mainly illiterate, were replaced by doctors and medical experts who were trusted for their education and literacy.

John Wolfe Dardess was an American historian of China, especially the Ming dynasty. He wrote nine books on the topic, including A Ming Society. He learned Chinese in the American military, and was posted to Taiwan. Earning his PhD from Columbia University in 1968, he taught at the University of Kansas from 1966 to 2002, becoming director of the Center for East Asian Studies in 1995. One obituary summarised his principal legacy as consisting “not in any particular interpretation he offered, but in a voracious appetite for delving into the written sources, the courage to ask stimulating new questions, and the historical imagination to wonder about the common humanity that linked the authors he read and their communities with his own times." He drew notice for pointing to continuities in Chinese history and drawing parallels between contemporary and Ming politics.

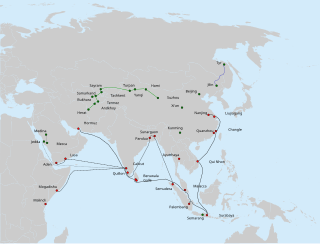

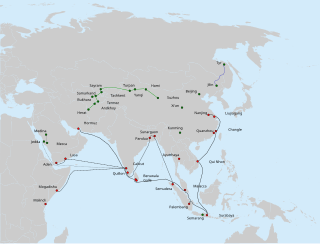

The History of Chinese Buddhism begins in the Han Dynasty, when Buddhism first began to arrive via the Silk Road networks. The early period of Chinese Buddhist history saw efforts to propagate Buddhism, establish institutions and translate Buddhist texts into Chinese. The effort was led by non-Chinese missionaries from India and Central Asia like Kumarajiva and Paramartha well as by great Chinese pilgrims and translators like Xuanzang.