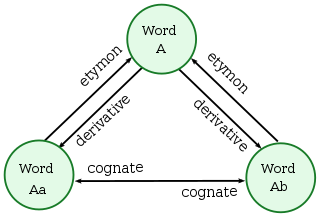

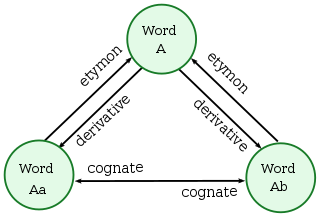

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, English, is also the world's most widely spoken language with an estimated 2 billion speakers. All Germanic languages are derived from Proto-Germanic, spoken in Iron Age Scandinavia, Iron Age Northern Germany and along the North Sea and Baltic coasts.

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family—English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, and Spanish—have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across several continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic; another nine subdivisions are now extinct.

The Germanic umlaut is a type of linguistic umlaut in which a back vowel changes to the associated front vowel (fronting) or a front vowel becomes closer to (raising) when the following syllable contains, , or.

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut is a system of apophony in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

The ruki sound law, also known as the ruki rule or iurk rule, is a historical sound change that took place in the satem branches of the Indo-European language family, namely in Balto-Slavic, Armenian, and Indo-Iranian. According to this sound law, an original *s changed to *š after the consonants *r, *k, *g, *gʰ and the semi-vowels *w (*u̯) and *y (*i̯), as well as the syllabic allophones *r̥, *i, and *u:

The Germanic language family is one of the language groups that resulted from the breakup of Proto-Indo-European (PIE). It in turn divided into North, West and East Germanic groups, and ultimately produced a large group of mediaeval and modern languages, most importantly: Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish (North); English, Dutch and German (West); and Gothic.

An alpha privative or, rarely, privative a is the prefix a- or an- that is used in Indo-European languages such as Sanskrit and Greek and in words borrowed therefrom to express negation or absence, for example the English words of Greek origin atypical, anesthetic, and analgesic.

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic, is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from c. 600 to c. 900. The main contemporary texts are dated c. 700–850; by 900 the language had already transitioned into early Middle Irish. Some Old Irish texts date from the 10th century, although these are presumably copies of texts written at an earlier time. Old Irish is thus forebear to Modern Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

Proto-Indo-European verbs reflect a complex system of morphology, more complicated than the substantive, with verbs categorized according to their aspect, using multiple grammatical moods and voices, and being conjugated according to person, number and tense. In addition to finite forms thus formed, non-finite forms such as participles are also extensively used.

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celtic is generally thought to have been spoken between 1300 and 800 BC, after which it began to split into different languages. Proto-Celtic is often associated with the Urnfield culture and particularly with the Hallstatt culture. Celtic languages share common features with Italic languages that are not found in other branches of Indo-European, suggesting the possibility of an earlier Italo-Celtic linguistic unity.

Internal reconstruction is a method of reconstructing an earlier state in a language's history using only language-internal evidence of the language in question.

Proto-Indo-European nominals include nouns, adjectives, and pronouns. Their grammatical forms and meanings have been reconstructed by modern linguists, based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. This article discusses nouns and adjectives; Proto-Indo-European pronouns are treated elsewhere.

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology.

The roots of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) are basic parts of words to carry a lexical meaning, so-called morphemes. PIE roots usually have verbal meaning like "to eat" or "to run". Roots never occurred alone in the language. Complete inflected verbs, nouns, and adjectives were formed by adding further morphemes to a root and potentially changing the root's vowel in a process called ablaut.

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other, mainly Romance, languages.

The boukólos rule is a phonological rule of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). It states that a labiovelar stop dissimilates to an ordinary velar stop next to the vowel *u or its corresponding glide *w.

In language change, analogical change occurs when one linguistic sign is changed in either form or meaning to reflect another item in the language system on the basis of analogy or perceived similarity. In contrast to regular sound change, analogy is driven by idiosyncratic cognitive factors and applies irregularly across a language system. This leads to what is known as Sturtevant's paradox: sound change is regular, but produces irregularity; analogy is irregular, but produces regularity.

Historical linguistics has made tentative postulations about and multiple varyingly different reconstructions of Proto-Germanic grammar, as inherited from Proto-Indo-European grammar. All reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk (*).