Further reading

- John Donne, Pseudo-martyr (1974 edition), Scolar Press.

Works by John Donne | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prose | |||||

| Poetry |

| ||||

| Settings to music |

| ||||

Pseudo-Martyr is a 1610 polemical prose tract in English by John Donne. It contributed to the religious pamphlet war of the time, and was Donne's first appearance in print. It argued that English Roman Catholics should take the Oath of Allegiance of James I of England. [1] It was printed by William Stansby for Walter Burre. [2]

Donne had converted from Catholicism, but had not moved decisively into the Protestant camp. From 1604 he became involved in controversial theology as an onlooker, assisting his friend Thomas Morton in a reply to James Anderton, commissioned by Richard Bancroft. [3] [4]

Donne entered directly into one of the major debates of the period, supporting Sir Edward Coke against the Jesuit Robert Parsons. Coke in Fift Part of the Reports (1606) had made a historical argument on the powers of the King of England in church matters. [5] Donne characterised the English mission, of Catholic priests trained to convert Protestants and sustain English Catholics, as "enemies to the dignity of all princes", and seditious because of the theories of temporal power of the Pope supported particularly by the Jesuits. [6] Donne used a comparison with the Circumcellions to denigrate Jesuit attitudes to martyrdom. [7]

A more subtle side to the argument is that it recognised that the oath had closed down the option of passive obedience to the king. Donne threw the onus of swearing onto individual conscience, discounting both arguments from the state and the authority of casuistry. The only acceptable basis was scripture and knowledge of nature, the duty of obedience being considered in the light of natural law. [8]

Pseudo-Martyr launched Donne into a career as a clergyman of the Church of England, one of the reasons he wrote it. He also aimed it at English Catholics. The work influenced Thomas James, who praised it. [9]

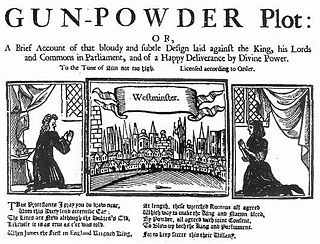

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against King James I by a group of English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who considered their actions attempted tyrannicide and who sought regime change in England after decades of religious persecution.

In English history, the penal laws were a series of laws that sought to uphold the establishment and State decreed religious monopoly of the Church of England against illegal and underground Catholics and Protestant nonconformists by imposing various forfeitures, civil penalties, and civil disabilities upon recusants from mandatory attendance at weekly Anglican Sunday services. The penal laws in general were repealed in the early 19th century during the process of Catholic Emancipation. Penal actions are civil in nature and were not English common law.

Robert Persons, later known as Robert Parsons, was an English Jesuit priest. He was a major figure in establishing the 16th-century "English Mission" of the Society of Jesus.

"The Vicar of Bray" is an eighteenth century satirical song recounting the career of The Vicar of Bray and his contortions of principle in order to retain his ecclesiastic office despite the changes in the Established Church through the course of several English monarchs. The song is particularly interesting because of the number of allusions to English religious and political doctrines and events crammed into it, justifying the close reading and annotation given here.

Robert Southwell, SJ, also Saint Robert Southwell, was an English Catholic priest of the Jesuit Order. He was also a poet, hymnodist, and clandestine missionary in Elizabethan England.

In Christianity, a martyr is a person who was or is killed for their testimony for Jesus or faith in Jesus. In years of the early church, stories depict this often occurring through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at the stake, or other forms of torture and capital punishment. The word martyr comes from the Koine word μάρτυς, mártys, which means "witness" or "testimony".

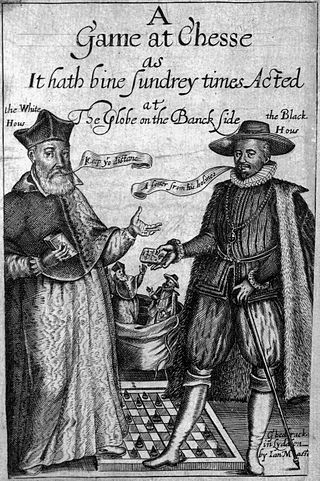

A Game at Chess is a comic satirical play by Thomas Middleton, first staged in August 1624 by the King's Men at the Globe Theatre. The play is notable for its political content, dramatizing a conflict between Spain and England.

Richard Verstegen, anglicised as Richard Verstegan and also known as Richard Rowlands, was an Anglo-Dutch antiquary, publisher, humorist and translator.

Irish Catholic Martyrs were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for both a life of heroic virtue and for dying for their Catholic faith between King Henry VIII and Catholic Emancipation in 1829. The canonization of Oliver Plunkett, who had been executed in London, as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1975 raised considerable public interest in other Irishmen and Irishwomen who had similarly died for their Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries. On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II beatified an additional 17 martyrs and assigned June 20, the anniversary of the 1584 martyrdom of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley, as their feast day. Many other causes for Roman Catholic Sainthood, however, remain under investigation.

Henry Morse was one of the Catholic Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

The Archpriest Controversy was the debate which followed the appointment of an archpriest by Pope Clement VIII to oversee the efforts of the Roman Catholic Church's missionary priests in England at the end of the sixteenth century.

James VI and I, King of Scots, King of England, and King of Ireland, faced many complicated religious challenges during his reigns in Scotland and England.

The Tumult of Thorn (Toruń), or Blood-Bath of Thorn refers to executions ordered in 1724 by the Polish supreme court under Augustus II the Strong of Saxony. During a religious conflict between Protestant townsfolk represented by mayor Johann Gottfried Rösner, and the Roman Catholic students of the Jesuit college in the city of Thorn (Toruń) in Royal Prussia, the college had been vandalised by a crowd of German Protestants. The mayor and nine other Lutheran officials were blamed for neglect of duty, sentenced to death, and executed on 7 December 1724.

The English Protestant Reformation was imposed by the English Crown, and submission to its essential points was exacted by the State with post-Reformation oaths. With some solemnity, by oath, test, or formal declaration, English churchmen and others were required to assent to the religious changes, starting in the sixteenth century and continuing for more than 250 years.

Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom dates back to Roman times. Attacks on the Church from a Protestant angle mostly began with the English and Irish Reformations which were launched by King Henry VIII and the Scottish Reformation which was led by John Knox. Within England, the Act of Supremacy 1534 declared the English crown to be "the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England" in place of the Pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. Ireland was brought under direct English control starting in 1536 during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. The Scottish Reformation in 1560 abolished Catholic ecclesiastical structures and rendered Catholic practice illegal in Scotland. Today, anti-Catholicism remains common in the United Kingdom, with particular relevance in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The Reformation in Ireland was a movement for the reform of religious life and institutions that was introduced into Ireland by the English administration at the behest of King Henry VIII of England. His desire for an annulment of his marriage was known as the King's Great Matter. Ultimately Pope Clement VII refused the petition; consequently, in order to give legal effect to his wishes, it became necessary for the King to assert his lordship over the Catholic Church in his realm. In passing the Acts of Supremacy in 1534, the English Parliament confirmed the King's supremacy over the Church in the Kingdom of England. This challenge to Papal supremacy resulted in a breach with the Catholic Church. By 1541, the Irish Parliament had agreed to the change in status of the country from that of a Lordship to that of Kingdom of Ireland.

The Toleration Act 1689, also referred to as the Act of Toleration, was an Act of the Parliament of England. Passed in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, it received royal assent on 24 May 1689.

Resistance theory is an aspect of political thought, discussing the basis on which constituted authority may be resisted, by individuals or groups. In the European context it came to prominence as a consequence of the religious divisions in the early modern period that followed the Protestant Reformation. Resistance theories could justify disobedience on religious grounds to monarchs, and were significant in European national politics and international relations in the century leading up to the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. They can also underpin and justify the concept of revolution as now understood. The resistance theory of the early modern period can be considered to predate the formulations of natural and legal rights of citizens, and to co-exist with considerations of natural law.

The Oath of Allegiance of 1606 was an oath requiring English Catholics to swear allegiance to James I over the Pope. It was adopted by Parliament the year after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. The oath was proclaimed law on 22 June 1606, it was also called the Oath of Obedience. Whatever effect it had on the loyalty of his subjects, it caused an international controversy lasting a decade and more.

Florimond de Raemond was a French jurist and antiquary. He is now known for a multi-volume history of recent events in France, written from a Roman Catholic point of view, and other popular works promoting the Counter-Reformation perspective against Protestant arguments. De Raemond was born in Agen and died in Bordeaux.