Hesiod was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.

In Greek mythology, Geryon, son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe, the grandson of Medusa and the nephew of Pegasus, was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides in the far west of the Mediterranean. A more literal-minded later generation of Greeks associated the region with Tartessos in southern Iberia. Geryon was often described as a monster with either three bodies and three heads, or three heads and one body, or three bodies and one head. He is commonly accepted as being mostly humanoid, with some distinguishing features and in mythology, famed for his cattle.

The Farnese Hercules is an ancient statue of Hercules, probably an enlarged copy made in the early third century AD and signed by Glykon, who is otherwise unknown; he was an Athenian but he may have worked in Rome. Like many other Ancient Roman sculptures it is a copy or version of a much older Greek original that was well known, in this case a bronze by Lysippos that would have been made in the fourth century BC. This original survived for over 1500 years until it was melted down by Crusaders in 1205 during the Sack of Constantinople. The enlarged copy was made for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, where the statue was recovered in 1546, and is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples. The heroically-scaled Hercules is one of the most famous sculptures of antiquity, and has fixed the image of the mythic hero in the European imagination.

The Galleria Borghese is an art gallery in Rome, Italy, housed in the former Villa Borghese Pinciana. At the outset, the gallery building was integrated with its gardens, but nowadays the Villa Borghese gardens are considered a separate tourist attraction. The Galleria Borghese houses a substantial part of the Borghese Collection of paintings, sculpture and antiquities, begun by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the nephew of Pope Paul V. The building was constructed by the architect Flaminio Ponzio, developing sketches by Scipione Borghese himself, who used it as a villa suburbana, a country villa at the edge of Rome.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is one of the best known Greek sculptures of Classical antiquity, depicting a solidly built, muscular, standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder. Rendered somewhat above life-size, the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later marble copies. The work nonetheless forms an important early example of both Classical Greek contrapposto and classical realism; as such, the iconic Doryphoros proved highly influential elsewhere in ancient art.

Carlo Marchionni was an Italian architect. He was also a sculptor and a virtuoso draughtsman, who mixed in the artistic and intellectual circles. He was born and died in Rome.

André Durand is a Canadian painter working in the European Hermetic tradition. He is influenced by artists such as Rubens, Titian, Michelangelo and Velázquez.

Paolo Giovio was an Italian physician, historian, biographer, and prelate.

Giovanni Pietro Bellori, also known as Giovan Pietro Bellori or Gian Pietro Bellori, was an Italian art theorist, painter and antiquarian, who is best known for his work Lives of the Artists, considered the seventeenth-century equivalent to Vasari's Vite. His Vite de' Pittori, Scultori et Architetti Moderni, published in 1672, was influential in consolidating and promoting the theoretical case for classical idealism in art. As an art historical biographer, he favoured classicising artists rather than Baroque artists to the extent of omitting some of the key artistic figures of 17th-century art altogether.

The Crouching Venus is a Hellenistic model of Venus surprised at her bath. Venus crouches with her right knee close to the ground, turns her head to the right and, in most versions, reaches her right arm over to her left shoulder to cover her breasts. To judge by the number of copies that have been excavated on Roman sites in Italy and France, this variant on Venus seems to have been popular.

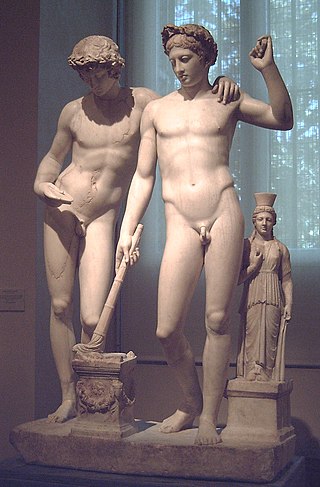

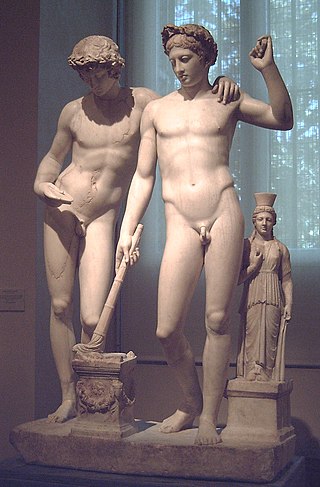

The Castor and Pollux group is an ancient Roman sculptural group of the 1st century AD, now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi was an Italian sculptor who worked in Rome, where he trained in the studio of the acclimatized Frenchman, Pierre-Étienne Monnot, and then in the workshop of Carlo Antonio Napolioni, a restorer of sculptures for Cardinal Alessandro Albani, who was to become a major patron of Cavaceppi, and a purveyer of antiquities and copies on his own account. The two sculptors shared a studio. Much of his work was in restoring antique Roman sculptures, making casts, copies, and fakes of antiques, fields in which he was pre-eminent and which brought him into contact with all the virtuosi: he was a close friend of and informant for Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Winckelmann's influence and Cardinal Albani's own evolving taste may have contributed to Cavaceppi's increased self-consciousness of the appropriateness of restorations — a field in which earlier sculptors had improvised broadly — evinced in his introductory essay to his Raccolta d'antiche statue, busti, teste cognite ed altre sculture antiche restaurate da Cav. Bartolomeo Cavaceppi scultore romano. The baroque taste in ornate restorations of antiquities had favoured finely pumiced polished surfaces, coloured marbles and mixed media, and highly speculative restorations of sometimes incongruous fragments. Only in the nineteenth century, would collectors begin for the first time to appreciate fragments of sculpture: a headless torso was not easily sold in eighteenth-century Rome.

The Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Reggio Calabria or Palazzo Piacentini is a museum in Reggio Calabria, southern Italy, housing an archaeological collection from sites in Magna Graecia.

The Giovio Series, also known as the Giovio Collection or Giovio Portraits, is a series of 484 portraits assembled by the 16th-century Italian Renaissance historian and biographer Paolo Giovio. It includes portraits of literary figures, rulers, statesmen and other dignitaries, many of which were done from life. Intended by Giovio as a public archive of famous men, the collection was originally housed in a specially-built museum on the shore of Lake Como. Although the original collection has not survived intact, a set of copies made for Cosimo I de' Medici now has a permanent home in Florence's Uffizi Gallery.

The Sleeping Ariadne, housed in the Vatican Museums in Vatican City, is a Roman Hadrianic copy of a Hellenistic sculpture of the Pergamene school of the 2nd century BC, and is one of the most renowned sculptures of Antiquity. The reclining figure in a chiton bound under her breasts half lies, half sits, her extended legs crossed at the calves, her head pillowed on her left arm, her right thrown over her head. Other Roman copies of this model exist: one, the "Wilton House Ariadne", is substantially unrestored, while another, the "Medici Ariadne" found in Rome, has been "seriously reworked in modern times", according to Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway. Two surviving statuettes attest to a Roman trade in reductions of this familiar figure. A variant Sleeping Ariadne is in the Prado Museum, Madrid. A later Roman variant found in the Villa Borghese gardens, Rome, is at the Louvre Museum.

The painted frieze at the Bodleian Library, in Oxford, United Kingdom, is a series of 202 portrait heads in what is now the Upper Reading Room. It was made in 1619, and the choice of worthies to include was advanced for its time, featuring Copernicus and Paracelsus as well as Protestant reformers. The portraits have been attributed to the London guild painter Thomas Knight; they were taken from at least ten different sources, according to current views.

Hermathena or Hermathene was a composite statue, or rather a herm, which may have been a terminal bust or a Janus-like bust, representing the Greek gods Hermes and Athena, or their Roman counterparts Mercury and Minerva.

The Jatta National Archaeological Museum in Ruvo di Puglia, a historic and artistic city in southern Italy, is housed in rooms of Palazzo Jatta and represents the only example in Italy of a nineteenth-century private collection that has remained unaltered from its original museographic concept. The finds preserved in the museum were collected by the archaeologist Giovanni Jatta in the early nineteenth century and his collection was subsequently enriched by his nephew of the same name and was sold to the Italian state in the twentieth century.

The Palazzo Massimo alle Terme is the main of the four sites of the Roman National Museum, along with the original site of the Baths of Diocletian, which currently houses the epigraphic and protohistoric section, Palazzo Altemps, home to the Renaissance collections of ancient sculpture, and the Crypta Balbi, home to the early medieval collection.