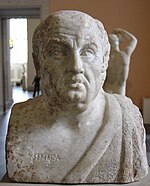

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger, usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

De Providentia is a short essay in the form of a dialogue in six brief sections, written by the Latin philosopher Seneca in the last years of his life. He chose the dialogue form to deal with the problem of the co-existence of the Stoic design of providence with the evil in the world—the so-called "problem of evil."

The Moralia is a set of essays ascribed to the 1st-century scholar Plutarch of Chaeronea. The eclectic collection contains 78 essays and transcribed speeches. They provide insights into Roman and Greek life, but they also include timeless observations. Many generations of Europeans have read or imitated them, including Michel de Montaigne, Renaissance Humanists and Enlightenment philosophers.

The gens Pompeia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, first appearing in history during the second century BC, and frequently occupying the highest offices of the Roman state from then until imperial times. The first of the Pompeii to obtain the consulship was Quintus Pompeius in 141 BC, but by far the most illustrious of the gens was Gnaeus Pompeius, surnamed Magnus, a distinguished general under the dictator Sulla, who became a member of the First Triumvirate, together with Caesar and Crassus. After the death of Crassus, the rivalry between Caesar and Pompeius led to the Civil War, one of the defining events of the final years of the Roman Republic.

Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus or Gallio was a Roman senator and brother of the writer Seneca. He is best known for dismissing an accusation brought against Paul the Apostle in Corinth.

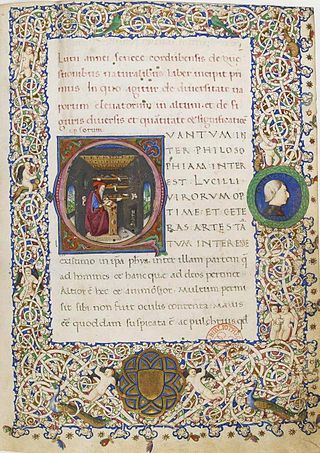

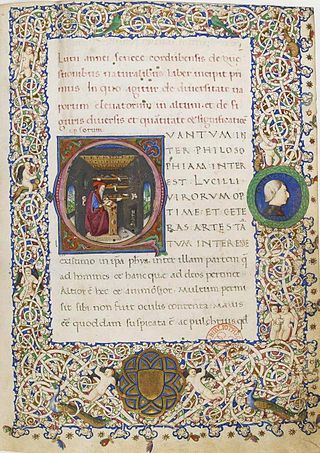

Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium, also known as the Moral Epistles and Letters from a Stoic, is a letter collection of 124 letters that Seneca the Younger wrote at the end of his life, during his retirement, after he had worked for the Emperor Nero for more than ten years. They are addressed to Lucilius Junior, the then procurator of Sicily, who is known only through Seneca's writings.

Pompeia Paulina was the wife of the statesman, philosopher, and orator Lucius Annaeus Seneca, and she was part of a circle of educated Romans who sought to lead a principled life under the emperor Nero. She was likely the daughter of Pompeius Paulinus, an eques from Arelate in Gaul. Seneca was the emperor's tutor and later became his political adviser and minister. In 65 AD Nero demanded that Seneca commit suicide, having accused Seneca of taking part in the Pisonian conspiracy against him. Paulina attempted to die with her husband, but survived the suicide attempt.

Phaedra is a Roman tragedy written by philosopher and dramatist Lucius Annaeus Seneca before 54 A.D. Its 1,280 lines of verse tell the story of Phaedra, wife of King Theseus of Athens and her consuming lust for her stepson Hippolytus. Based on Greek mythology and the tragedy Hippolytus by Euripides, Seneca's Phaedra is one of several artistic explorations of this tragic story. Seneca portrays Phaedra as self-aware and direct in the pursuit of her stepson, while in other treatments of the myth, she is more of a passive victim of fate. This Phaedra takes on the scheming nature and the cynicism often assigned to the nurse character.

De Vita Beata is a dialogue written by Seneca the Younger around the year 58 AD. It was intended for his older brother Gallio, to whom Seneca also dedicated his dialogue entitled De Ira. It is divided into 28 chapters that present the moral thoughts of Seneca at their most mature. Seneca explains that the pursuit of happiness is the pursuit of reason – reason meant not only using logic, but also understanding the processes of nature.

Seneca's Consolations refers to Seneca’s three consolatory works, De Consolatione ad Marciam, De Consolatione ad Polybium, De Consolatione ad Helviam, written around 40–45 AD.

Naturales quaestiones is a Latin work of natural philosophy written by Seneca around AD 65. It is not a systematic encyclopedia like the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, though with Pliny's work it represents one of the few Roman works dedicated to investigating the natural world. Seneca's investigation takes place mainly through the consideration of the views of other thinkers, both Greek and Roman, though it is not without original thought. One of the most unusual features of the work is Seneca's articulation of the natural philosophy with moralising episodes that seem to have little to do with the investigation. Much of the recent scholarship on the Naturales Quaestiones has been dedicated to explaining this feature of the work. It is often suggested that the purpose of this combination of ethics and philosophical 'physics' is to demonstrate the close connection between these two parts of philosophy, in line with the thought of Stoicism.

Medea is a fabula crepidata of about 1027 lines of verse written by Seneca the Younger. It is generally considered to be the strongest of his earlier plays. It was written around 50 CE. The play is about the vengeance of Medea against her betraying husband Jason and King Creon. The leading role, Medea, delivers over half of the play's lines. Medea addresses many themes, one being that the title character represents "payment" for humans' transgression of natural laws. She was sent by the gods to punish Jason for his sins. Another theme is her powerful voice that cannot be silenced, not even by King Creon.

Otium is a Latin abstract term which has a variety of meanings, including leisure time for "self-realization activities" such as eating, playing, relaxing, contemplation, and academic endeavors. It sometimes relates to a time in a person's retirement after previous service to the public or private sector, as opposed to "active public life". Otium can be a temporary or sporadic time of leisure. It can have intellectual, virtuous, or immoral implications.

De Beneficiis is a first-century work by Seneca the Younger. It forms part of a series of moral essays composed by Seneca. De Beneficiis concerns the award and reception of gifts and favours within society, and examines the complex nature and role of gratitude within the context of Stoic ethics.

De Clementia is a two volume (incomplete) hortatory essay written in AD 55–56 by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, to the emperor Nero in the first five years of his reign.

De Tranquillitate Animi is a Latin work by the Stoic philosopher Seneca. The dialogue concerns the state of mind of Seneca's friend Annaeus Serenus, and how to cure Serenus of anxiety, worry and disgust with life.

De Ira is a Latin work by Seneca. The work defines and explains anger within the context of Stoic philosophy, and offers advice which utilizes virtue and personal improvement in order to prevent anger.

De Otio is a 1st-century Latin work by Seneca. It survives in a fragmentary state. The work concerns the rational use of spare time, whereby one can still actively aid humankind by engaging in wider questions about nature and the universe.

De Constantia Sapientis is a moral essay written by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, sometime around 55 AD. The work celebrates the imperturbability of the ideal Stoic sage, who with an inner firmness, is strengthened by injury and adversity.

The Stoic Opposition is the name given to a group of Stoic philosophers who actively opposed the autocratic rule of certain emperors in the 1st-century, particularly Nero and Domitian. Most prominent among them was Thrasea Paetus, an influential Roman senator executed by Nero. They were held in high regard by the later Stoics Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Thrasea, Rubellius Plautus and Barea Soranus were reputedly students of the famous Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus and as all three were executed by Nero they became known collectively as the Stoic martyrs.