Chrysippus of Soli was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When Cleanthes died, around 230 BC, Chrysippus became the third head of the Stoic school. A prolific writer, Chrysippus expanded the fundamental doctrines of Cleanthes' mentor Zeno of Citium, the founder and first head of the school, which earned him the title of the Second Founder of Stoicism.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger, usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Posidonius "of Apameia" or "of Rhodes", was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher native to Apamea, Syria. He was considered the most learned man of his time and, possibly, of the entire Stoic school. After a period learning Stoic philosophy from Panaetius in Athens, he spent many years in travel and scientific researches in Spain, Africa, Italy, Gaul, Liguria, Sicily and on the eastern shores of the Adriatic. He settled as a teacher at Rhodes where his fame attracted numerous scholars. Next to Panaetius he did most, by writings and personal lectures, to spread Stoicism to the Roman world, and he became well known to many leading men, including Pompey and Cicero.

Hecato or Hecaton of Rhodes was a Greek Stoic philosopher.

Panaetius of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doctrines to the city, thanks to the patronage of Scipio Aemilianus. After the death of Scipio in 129 BC, he returned to the Stoic school in Athens, and was its last undisputed scholarch. With Panaetius, Stoicism became much more eclectic. His most famous work was his On Duties, the principal source used by Cicero in his own work of the same name.

De Providentia is a short essay in the form of a dialogue in six brief sections, written by the Latin philosopher Seneca in the last years of his life. He chose the dialogue form to deal with the problem of the co-existence of the Stoic design of providence with the evil in the world—the so-called "problem of evil."

Aristo of Chios, also spelled Ariston, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and colleague of Zeno of Citium. He outlined a system of Stoic philosophy that was, in many ways, closer to earlier Cynic philosophy. He rejected the logical and physical sides of philosophy endorsed by Zeno and emphasized ethics. Although agreeing with Zeno that Virtue was the supreme good, he rejected the idea that morally indifferent things such as health and wealth could be ranked according to whether they are naturally preferred. An important philosopher in his day, his views were eventually marginalized by Zeno's successors.

Diogenes of Babylon was a Stoic philosopher. He was the head of the Stoic school in Athens, and he was one of three philosophers sent to Rome in 155 BC. He wrote many works, but none of his writings survived, except as quotations by later writers.

De Brevitate Vitae is a moral essay written by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, sometime around the year 49 AD, to his father-in-law Paulinus. The philosopher brings up many Stoic principles on the nature of time, namely that people waste much of it in meaningless pursuits. According to the essay, nature gives people enough time to do what is really important and the individual must allot it properly. In general, time is best used by living in the present moment in pursuit of the intentional, purposeful life.

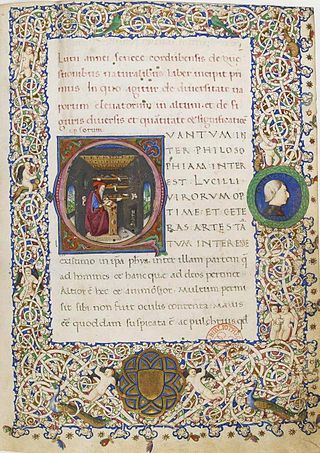

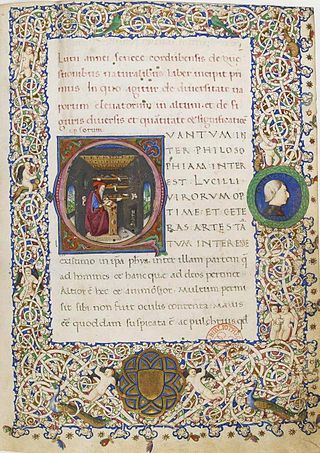

Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium, also known as the Moral Epistles and Letters from a Stoic, is a letter collection of 124 letters that Seneca the Younger wrote at the end of his life, during his retirement, after he had worked for the Emperor Nero for more than ten years. They are addressed to Lucilius Junior, the then procurator of Sicily, who is known only through Seneca's writings.

Stoic passions are various forms of emotional suffering in Stoicism, a school of Hellenistic philosophy.

De Vita Beata is a dialogue written by Seneca the Younger around the year 58 AD. It was intended for his older brother Gallio, to whom Seneca also dedicated his dialogue entitled De Ira. It is divided into 28 chapters that present the moral thoughts of Seneca at their most mature. Seneca explains that the pursuit of happiness is the pursuit of reason – reason meant not only using logic, but also understanding the processes of nature.

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The Stoics believed that the practice of virtue is enough to achieve eudaimonia: a well-lived life. The Stoics identified the path to achieving it with a life spent practicing the four cardinal virtues in everyday life — prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice — as well as living in accordance with nature. It was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BCE.

Naturales quaestiones is a Latin work of natural philosophy written by Seneca around AD 65. It is not a systematic encyclopedia like the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, though with Pliny's work it represents one of the few Roman works dedicated to investigating the natural world. Seneca's investigation takes place mainly through the consideration of the views of other thinkers, both Greek and Roman, though it is not without original thought. One of the most unusual features of the work is Seneca's articulation of the natural philosophy with moralising episodes that seem to have little to do with the investigation. Much of the recent scholarship on the Naturales Quaestiones has been dedicated to explaining this feature of the work. It is often suggested that the purpose of this combination of ethics and philosophical 'physics' is to demonstrate the close connection between these two parts of philosophy, in line with the thought of Stoicism.

De Beneficiis is a first-century work by Seneca the Younger. It forms part of a series of moral essays composed by Seneca. De Beneficiis concerns the award and reception of gifts and favours within society, and examines the complex nature and role of gratitude within the context of Stoic ethics.

De Clementia is a two volume (incomplete) hortatory essay written in AD 55–56 by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, to the emperor Nero in the first five years of his reign.

De Tranquillitate Animi is a Latin work by the Stoic philosopher Seneca. The dialogue concerns the state of mind of Seneca's friend Annaeus Serenus, and how to cure Serenus of anxiety, worry and disgust with life.

De Otio is a 1st-century Latin work by Seneca. It survives in a fragmentary state. The work concerns the rational use of spare time, whereby one can still actively aid humankind by engaging in wider questions about nature and the universe.

De Constantia Sapientis is a moral essay written by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, sometime around 55 AD. The work celebrates the imperturbability of the ideal Stoic sage, who with an inner firmness, is strengthened by injury and adversity.

On Passions, also translated as On Emotions or On Affections, is a work by the Greek Stoic philosopher Chrysippus dating from the 3rd-century BCE. The book has not survived intact, but around seventy fragments from the work survive in a polemic written against it in the 2nd-century CE by the philosopher-physician Galen. In addition Cicero summarises substantial portions of the work in his 1st-century BCE work Tusculan Disputations. On Passions consisted of four books; of which the first three discussed the Stoic theory of emotions and the fourth book discussed therapy and had a separate title—Therapeutics. Most surviving quotations come from Books 1 and 4, although Galen also provides an account of Book 2 drawn from the 1st-century BCE Stoic philosopher Posidonius. Little or nothing is known about Book 3.