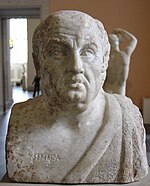

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger, usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder, also known as Seneca the Rhetorician, was a Roman writer, born of a wealthy equestrian family of Corduba, Hispania. He wrote a collection of reminiscences about the Roman schools of rhetoric, six books of which are extant in a more or less complete state and five others in epitome only. His principal work, a history of Roman affairs from the beginning of the Civil Wars until the last years of his life, is almost entirely lost to posterity. Seneca lived through the reigns of three significant emperors; Augustus, Tiberius and Caligula. He was the father of Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus, best known as a Proconsul of Achaia; his second son was the dramatist and Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger (Lucius), who was tutor of Nero, and his third son, Marcus Annaeus Mela, became the father of the poet Lucan.

The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies is a 1925 essay by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss that is the foundation of social theories of reciprocity and gift exchange.

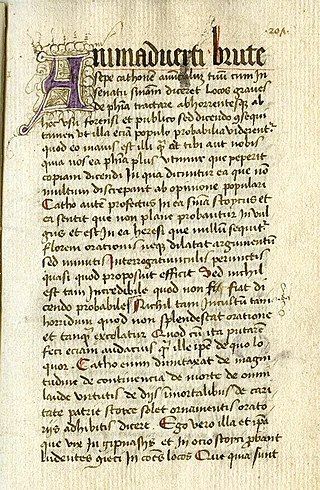

De Officiis is a 44 BC treatise by Marcus Tullius Cicero divided into three books, in which Cicero expounds his conception of the best way to live, behave, and observe moral obligations. The posthumously published work discusses what is honorable, what is to one's advantage, and what to do when the honorable and private gain apparently conflict. For the first two books Cicero was dependent on the Stoic philosopher Panaetius, but wrote more independently for the third book.

Panaetius of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doctrines to the city, thanks to the patronage of Scipio Aemilianus. After the death of Scipio in 129 BC, he returned to the Stoic school in Athens, and was its last undisputed scholarch. With Panaetius, Stoicism became much more eclectic. His most famous work was his On Duties, the principal source used by Cicero in his own work of the same name.

De Providentia is a short essay in the form of a dialogue in six brief sections, written by the Latin philosopher Seneca in the last years of his life. He chose the dialogue form to deal with the problem of the co-existence of the Stoic design of providence with the evil in the world—the so-called "problem of evil."

De Brevitate Vitae is a moral essay written by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, sometime around the year 49 AD, to his father-in-law Paulinus. The philosopher brings up many Stoic principles on the nature of time, namely that people waste much of it in meaningless pursuits. According to the essay, nature gives people enough time to do what is really important and the individual must allot it properly. In general, time is best used by living in the present moment in pursuit of the intentional, purposeful life.

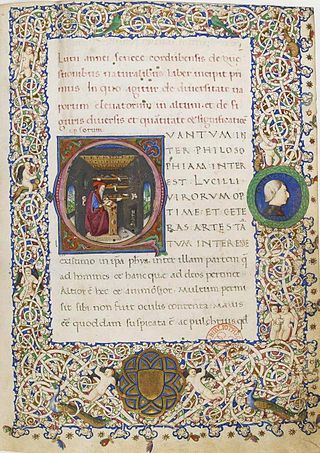

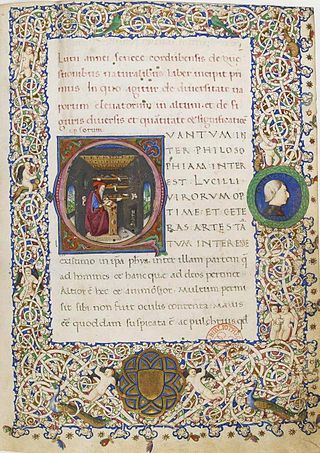

Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium, also known as the Moral Epistles and Letters from a Stoic, is a letter collection of 124 letters that Seneca the Younger wrote at the end of his life, during his retirement, after he had worked for the Emperor Nero for more than ten years. They are addressed to Lucilius Junior, the then procurator of Sicily, who is known only through Seneca's writings.

Neostoicism was a philosophical movement that arose in the late 16th century from the works of Justus Lipsius, and sought to combine the beliefs of Stoicism and Christianity. Lipsius was Flemish and a Renaissance humanist. The movement took on the nature of religious syncretism, although modern scholarship does not consider that it resulted in a successful synthesis. The name "neostoicism" is attributed to two Roman Catholic authors, Léontine Zanta and Julien-Eymard d'Angers.

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The Stoics believed that the practice of virtue is enough to achieve eudaimonia: a well-lived life. The Stoics identified the path to achieving it with a life spent practicing the four virtues in everyday life—wisdom, courage, temperance or moderation, and justice—as well as living in accordance with nature. It was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BCE.

Naturales quaestiones is a Latin work of natural philosophy written by Seneca around AD 65. It is not a systematic encyclopedia like the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, though with Pliny's work it represents one of the few Roman works dedicated to investigating the natural world. Seneca's investigation takes place mainly through the consideration of the views of other thinkers, both Greek and Roman, though it is not without original thought. One of the most unusual features of the work is Seneca's articulation of the natural philosophy with moralising episodes that seem to have little to do with the investigation. Much of the recent scholarship on the Naturales Quaestiones has been dedicated to explaining this feature of the work. It is often suggested that the purpose of this combination of ethics and philosophical 'physics' is to demonstrate the close connection between these two parts of philosophy, in line with the thought of Stoicism.

Otium is a Latin abstract term which has a variety of meanings, including leisure time for "self-realization activities" such as eating, playing, relaxing, contemplation, and academic endeavors. It sometimes relates to a time in a person's retirement after previous service to the public or private sector, as opposed to "active public life". Otium can be a temporary or sporadic time of leisure. It can have intellectual, virtuous, or immoral implications.

De Clementia is a two volume (incomplete) hortatory essay written in AD 55–56 by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, to the emperor Nero in the first five years of his reign.

De Tranquillitate Animi is a Latin work by the Stoic philosopher Seneca. The dialogue concerns the state of mind of Seneca's friend Annaeus Serenus, and how to cure Serenus of anxiety, worry and disgust with life.

De Ira is a Latin work by Seneca. The work defines and explains anger within the context of Stoic philosophy, and offers therapeutic advice on what to do to prevent anger.

De Otio is a 1st-century Latin work by Seneca. It survives in a fragmentary state. The work concerns the rational use of spare time, whereby one can still actively aid humankind by engaging in wider questions about nature and the universe.

The Paradoxa Stoicorum is a work by the academic skeptic philosopher Cicero in which he attempts to explain six famous Stoic sayings that appear to go against common understanding: (1) virtue is the sole good; (2) virtue is the sole requisite for happiness; (3) all good deeds are equally virtuous and all bad deeds equally vicious; (4) all fools are mad; (5) only the wise are free, whereas all fools are enslaved; and (6) only the wise are rich.

Miriam Tamara Griffin was an American classical scholar and tutor of ancient history at Somerville College at the University of Oxford from 1967 to 2002. She was a scholar of Roman history and ancient thought, and wrote books on the Emperor Nero and his tutor, Seneca, encouraging an appreciation of the philosophical writings of the ancient Romans within their historical context.

De Constantia Sapientis is a moral essay written by Seneca the Younger, a Roman Stoic philosopher, sometime around 55 AD. The work celebrates the imperturbability of the ideal Stoic sage, who with an inner firmness, is strengthened by injury and adversity.

The Stoic Opposition is the name given to a group of Stoic philosophers who actively opposed the autocratic rule of certain emperors in the 1st-century, particularly Nero and Domitian. Most prominent among them was Thrasea Paetus, an influential Roman senator executed by Nero. They were held in high regard by the later Stoics Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Thrasea, Rubellius Plautus and Barea Soranus were reputedly students of the famous Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus and as all three were executed by Nero they became known collectively as the Stoic martyrs.