World War I impacted on many aspects of everyday life in Queensland , Australia. Over 58,000 Queenslanders fought in World War I and over 10,000 of them died. [1]

World War I impacted on many aspects of everyday life in Queensland , Australia. Over 58,000 Queenslanders fought in World War I and over 10,000 of them died. [1]

The outbreak of war created a heightened sense of patriotism; the recruitment call for Queenslanders to volunteer for the Australian Imperial Force met its initial quota of 2500 enlisted men by September 1914. [2]

As Australian soldiers marched off to World War I on a wave of patriotism, Queensland was in a state of political flux. With an increasingly active and unionised workforce, vocal and radical anti-war groups, and a change of government in 1915, the people of Queensland struggled to find a partisan approach towards the war. Despite these issues, the Queensland Government had a duty to support the war effort, to keep social conflict to a minimum, to provide reasonable living and working conditions for its citizens, and to look to the welfare of returned soldiers and families of soldiers who died. [3]

As the most visible public servants across the state, the Queensland Police were intimately involved in government actions throughout the war. Additional duties were thrust upon them, even as their numbers decreased due to police officers enlisting in the armed forces. These duties included enforcing some of the provisions of the National Security Regulations, and the War Precautions (Alien Registrations) Regulations. Police were required to maintain the internal security of the state and to administer support to the war effort and to recruitment. One of their earliest tasks was tracking members of the British reserve forces in Australia to notify them of their call-up on the outbreak of war. Foreign-born reservists of combatant counties were considered to be prisoners of war; some were interned while others were paroled to move freely within the community provided they regularly reported to police. [3]

Anti-German sentiment led to a Cabinet direction in 1916 that persons of German or Austrian birth were not to be employed in the Queensland Public Service if there were British nationals available for the task. (At that time, those born or naturalised in Australia were British nationals as there was no separate status of Australian citizenship.) However, due to the shortage in personnel, the 65 German-born Queensland police officers were not dismissed, though they were scrutinised by their senior officers. Throughout the war Queensland police were required to maintain secret surveillance on members of the Turkish, Syrian, Bulgarian, Greek, and Italian communities across the state. At the behest of the Queensland War Council, police also provided assessments of the moral character of soldiers' wives who were receiving assistance. [3]

The Queensland War Council and subsequent Local War Council Committees were established in 1915 principally to help recruit and provide support for returned soldiers and for the families of those who were disabled or killed in war. The Queensland War Council Chairperson was the Premier of Queensland. The council was the primary force in the repatriation of Queensland soldiers until the Australian Government established a similar entity in early 1918. In the early part of the war the council supported the establishment of the Anzac cottages and the tuberculosis home schemes. The Queensland Government's Discharged Soldiers Settlement Act 1917 provided land and financial assistance for which all returned servicemen could apply. Another measure to support returned servicemen was the preferential employment scheme adopted by the Queensland Public Service. [3]

The Queensland Government did not require women to take employment in war industries as they had in Britain, and full-time employment for women did not significantly increase. Relatively small numbers of women were accepted as military nurses, and only after prolonged lobbying were the Voluntary Aid Detachments of the Australian Red Cross able to send units to overseas hospitals. It was in voluntary organisations that women made their direct and most significant contributions to the war effort. These organisations took on the responsibility of providing comforts for sick and wounded soldiers here and abroad, and providing frontline troops with morale-building gifts and articles of clothing. The Red Cross Society began work almost immediately upon the declaration of war. From initial knitting circles, the scope of Red Cross support expanded rapidly to include teaching handcrafts to convalescent soldiers, mending hospital clothes and providing food and other necessary supplies to local and overseas military hospitals. So strong was the mobilisation of Red Cross "kitchen ladies" that in addition to providing food for the Rosemount, Kangaroo Point and Lytton military hospitals, they were also able to supplement food to asylums, orphanages, and public hospitals. Other voluntary organisations - the National Council of Women (which was an amalgam of 41 other societies), the Queensland Soldiers' Comfort Fund, the Babies of the Allies Clothing Society, the Women's Mutual Service Club, the Soldier's Pastime Club, Sailor's and Soldiers Residential Club, and the Christmas Box Fund to name but a few - provided similar services. The social and economic value of such voluntary work was considerable. [3]

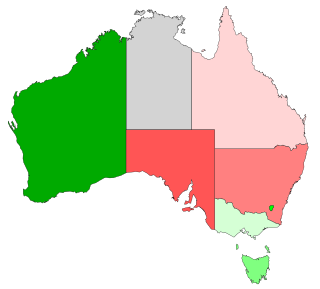

Queensland women also exercised their right to vote during the war years. The Military Service Referendum Act 1916 and the War Precautions (Military Service Referendum) Regulations 1917 were contentious, the debate concerning conscription dividing Australian society on religious and political grounds. Women rose to their feet to speak publicly in support or against the proposals. Both attempts to conscript men for military service were defeated. At the height of the second conscription referendum, the Queensland Government, which was the only state with an anti-conscription position, took the extraordinary step of stationing armed police on the Queensland Government Printing Office to prevent the Australian Government censoring anti-conscription material in the Raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office. [3]

Queensland society changed considerably during the war years. The strains on the local economy prompted the government to embrace the acquisition of state-owned industries in an effort to keep living standards affordable. This social experiment also divided the population, and, as the war drew to a conclusion, the state was no less polarised by political ideology. However, there was a shared empathy for the survivors of Queensland's 57,705 enlistees, for those who were killed, and for their families. This manifested itself in many ways but particularly in the erection of World War I memorials in many towns across the state and in the annual Anzac Day ceremonies. [3]

The Conscription Crisis of 1917 was a political and military crisis in Canada during World War I. It was mainly caused by disagreement on whether men should be conscripted to fight in the war, but also brought out many issues regarding relations between French Canadians and English Canadians. The vast majority of French Canadians opposed conscription; they felt that they had no particular loyalty to either Britain or France. Led by Henri Bourassa, they felt their only loyalty was to Canada. English Canadians supported the war effort as they felt stronger ties to the British Empire. On January 1, 1918, the Unionist government began to enforce the Military Service Act. The Act caused 404,385 men to be liable for military service, from which 385,510 sought exemption.

The First Australian Imperial Force was the main expeditionary force of the Australian Army during the First World War. It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following Britain's declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division and one light horse brigade. The infantry division subsequently fought at Gallipoli between April and December 1915, with a newly raised second division, as well as three light horse brigades, reinforcing the committed units.

Conscription in Australia, also known as National Service following the Second World War, has a controversial history which dates back to the implementation of compulsory military training and service in the first years of Australia's nationhood. Military conscription for peacetime service was abolished in 1972.

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

The 1916 Australian referendum, concerning how conscripted soldiers could be deployed, was held on 28 October 1916. It was the first non-binding Australian referendum, and contained one proposition, which was Prime Minister Billy Hughes' proposal to allow conscripted troops to serve overseas during World War I.

The 1917 Australian referendum was held on 20 December 1917. It contained one question.

Compulsory military training (CMT), a form of conscription, was practised for males in New Zealand between 1909 and 1972. Military training in New Zealand has been voluntary before then and ever since.

The history of Queensland encompasses both a long Aboriginal Australian presence as well as the more recent periods of European colonisation and as a state of Australia. Before being charted and claimed for the Kingdom of Great Britain by Lieutenant James Cook in 1770, the coast of north-eastern Australia was explored by Dutch and French navigators. Queensland separated from the Colony of New South Wales as a self-governing Crown colony in 1859. In 1901 it became one of the six founding states of Australia.

The Conscription Crisis of 1918 stemmed from a move by the British government to impose conscription in Ireland in April 1918 during the First World War. Vigorous opposition was led by trade unions, Irish nationalist parties and Roman Catholic bishops and priests. A conscription law was passed but was never put in effect; no one in Ireland was drafted into the British Army. The proposal and backlash galvanised support for political parties which advocated Irish separatism and influenced events in the lead-up to the Irish War of Independence.

The Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) was a voluntary unit of civilians providing nursing care for military personnel in the United Kingdom and various other countries in the British Empire. The most important periods of operation for these units were during World War I and World War II. Although VADs were intimately bound up in the war effort, they were not military nurses, as they were not under the control of the military, unlike the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps, the Princess Mary's Royal Air Force Nursing Service, and the Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service. The VAD nurses worked in field hospitals, i.e., close to the battlefield, and in longer-term places of recuperation back in Britain.

In Australia, the outbreak of World War I was greeted with considerable enthusiasm. Even before Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the nation pledged its support alongside other states of the British Empire and almost immediately began preparations to send forces overseas to engage in the conflict. The first campaign that Australians were involved in was in German New Guinea after a hastily raised force known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force was dispatched in September 1914 from Australia and seized and held German possessions in the Pacific. At the same time another expeditionary force, initially consisting of 20,000 men and known as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), was raised for service overseas.

Opposition to World War I was widespread during the conflict and included socialists, anarchists, syndicalists and Marxists as well as Christian pacifists, anti-colonial nationalists, feminists, intellectuals, and the working class.

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

Anzac Avenue is a heritage-listed major arterial road lined with trees in the City of Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia. It runs 17.8 kilometres (11.1 mi) from Petrie to Redcliffe, with most of the route signed as state route 71. The route was formerly the main route to the Redcliffe peninsula, until the Hornibrook Bridge was opened in 1935.

During the second half of World War I, the First Australian Imperial Force experienced a shortage of men as the number of men volunteering to fight overseas declined and the casualty rate increased. At the time, military service within the Commonwealth of Australia and its territories was compulsory for Australian men, but that requirement did not extend to conflict outside of Australia. In 1916, Prime Minister Billy Hughes called a plebiscite to determine public support for extending conscription to include military service outside the Commonwealth for the duration of the war. The referendum, held on 28 October 1916, narrowly rejected the proposal. A second plebiscite, held a year later on 20 December 1917, also failed to gain a majority.

Australian women in World War I, were involved in militaries, and auxiliary organisations of the Allied forces abroad, and in administration, fundraising, campaigning, and other war time efforts on home front in Australia. They also played a role in the anti-war movement, protesting conscription, as well as food shortages driven by war activities. The role of women in Australian society was already shifting when the war broke out, yet their participation on all fronts during the Great War escalated these changes significantly.

In 1914, war was declared between Great Britain and Germany. Queensland independently claimed war against Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire, uncertain if the Australian Constitution enabled a declaration of war by the Commonewealth of Australia. In the first few weeks that followed the declaration of war, existing militia were deployed to the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force which attacked and occupied German New Guinea. Heightened patriotism resulted in 2500 Queensland men volunteering for the Australian Imperial Force. German military reservists were arrested and detained.

During World War I, extensive military recruitment took place in Queensland. Although many enlisted voluntarily, there was considerable pressure for the unwilling to enlist, including two unsuccessful attempts to introduce conscription in 1916 and 1917. Overall, more than 57,700 Queenslanders fought in World War I and over 10,000 of them died.

Formed in Melbourne, Australia in 1915, the Women’s Peace Army was an Australian anti-war socialist movement that sought to mobilise and unite women, regardless of political or religious beliefs, in their opposition to war. Autonomous branches of the Women’s Peace Army were also established in the Australian cities of Sydney and Brisbane.

In November 1917 during World War I, the Australian Government conducted a raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office in Brisbane. The aim of the raid was to confiscate any copies of the Hansard, the official parliamentary transcript, which documented anti-conscription sentiments that had been aired in the state's parliament.

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland home front during the First World War" (January 2014) by Brian Rough published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 24 February 2016, archived on 24 February 2016).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland home front during the First World War" (January 2014) by Brian Rough published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 24 February 2016, archived on 24 February 2016).

![]() Media related to Queensland in World War I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Queensland in World War I at Wikimedia Commons