The Nationalist Party, also known as the National Party, was an Australian political party. It was formed in February 1917 from a merger between the Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the latter formed by Prime Minister Billy Hughes and his supporters after the 1916 Labor Party split over World War I conscription. The Nationalist Party was established as a 'united' non-Labor opposition that had remained a political trend once the Labor party established itself in federal politics. The party was in government until electoral defeat in 1929. From that time it was the main opposition to the Labor Party until it merged with pro-Joseph Lyons Labor defectors to form the United Australia Party (UAP) in 1931. The party is a direct ancestor of the Liberal Party of Australia, the main centre-right party in Australia.

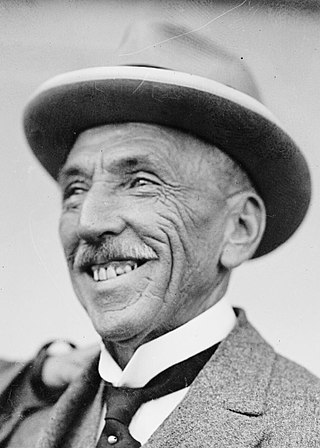

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), and was particularly notable for leading the party to its first federal election victory and first majority government at the 1910 federal election.

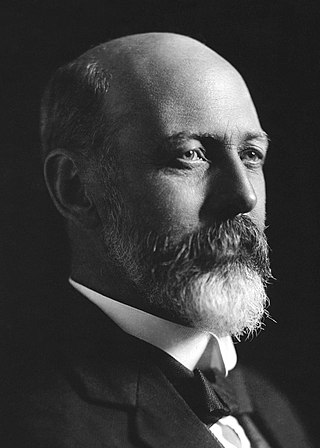

William Morris Hughes was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics spanned several decades. He was a member of the federal parliament from the Federation of Australia in 1901 until his death in 1952, and is the only person to have served as a parliamentarian for more than 50 years. He represented six political parties during his career, leading five, outlasting four, and being expelled from three.

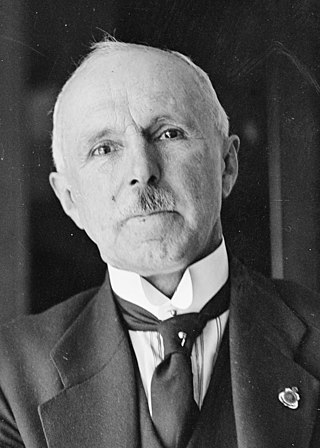

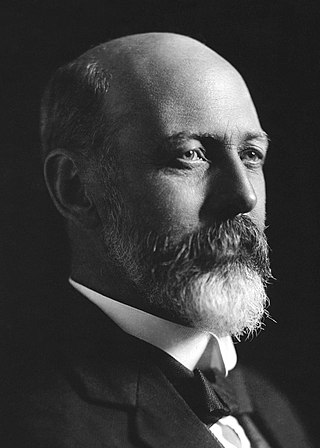

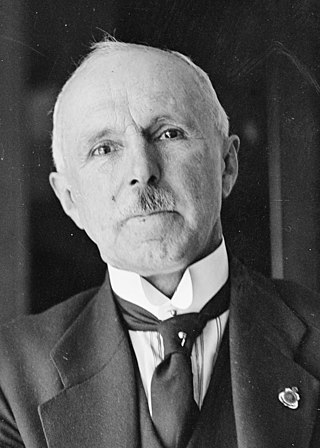

Sir Joseph Cook was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the sixth prime minister of Australia from 1913 to 1914. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party, having previously been leader of the Anti-Socialist Party from 1908 to 1909. His victory at the 1913 election marked the first time that a centre-right party had won a majority at an Australian federal election.

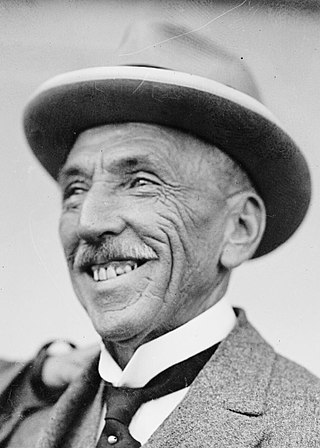

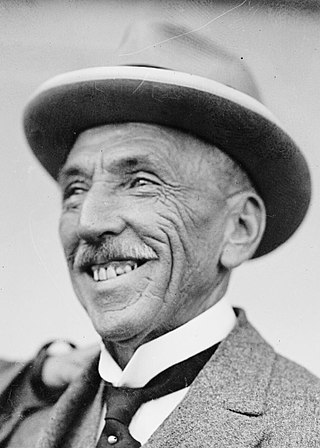

Francis Gwynne Tudor was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy Hughes.

Conscription in Australia, also known as National Service following the Second World War, has a controversial history which dates back to the implementation of compulsory military training and service in the first years of Australia's nationhood. Military conscription for peacetime service was abolished in 1972.

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Prime Minister of Australia when anti-conscriptionist Andrew Fisher resigned in 1915. He formed the new party for himself and his followers after he was expelled from the ALP a month after the 1916 plebiscite on conscription in Australia. Hughes held a pro-conscription stance in relation to World War I.

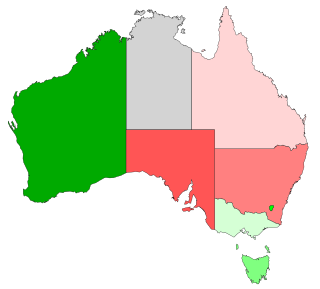

The 1916 Australian referendum, concerning how conscripted soldiers could be deployed, was held on 28 October 1916. It was the first non-binding Australian referendum, and contained one proposition, which was Prime Minister Billy Hughes' proposal to allow conscripted troops to serve overseas during World War I.

The 1917 Australian referendum was held on 20 December 1917. It contained one question.

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, the Nationalist Party, and the United Australia Party; he served as a cabinet minister under prime ministers from all four parties.

The Electoral district of Brown Hill-Ivanhoe was a Legislative Assembly electorate in the state of Western Australia. It covered part of the Goldfields city of Boulder, near Kalgoorlie, and neighbouring mining areas. It was created at the 1911 redistribution out of the former seats of Brown Hill and Ivanhoe, and was first contested at the 1911 election. It was abolished in the 1948 redistribution, with its area split between the neighbouring electorates of Boulder and Hannans, taking effect from the 1950 election. The seat was a very safe one for the Labor Party.

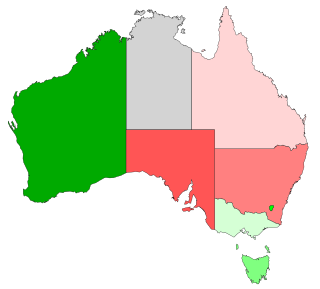

The 1919 Australian federal election was held on 13 December 1919 to elect members to the Parliament of Australia. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist Party government won re-election, with Prime Minister Billy Hughes continuing in office.

The 1917 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 5 May 1917. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist Party, led by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, defeated the opposition Labor Party led by Frank Tudor in a landslide.

Richard Armstrong Crouch was an Australian politician. His two periods as a member of the House of Representatives were separated by the First World War, during which he became an anti-conscription activist and changed his political affiliation. Crouch was a Protectionist and Liberal during his first period as an MP, but later became involved in the labour movement and represented the Australian Labor Party (ALP) during his second term. He is one of the few MPs to move to the ALP after previously belonging to an anti-Labor party.

This is a list of members of the Australian Senate from 1914 to 1917. The 5 September 1914 election was a double dissolution called by Prime Minister of Australia Joseph Cook in an attempt to gain control of the Senate. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and all 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Commonwealth Liberal Party was defeated by the opposition Australian Labor Party led by Andrew Fisher, who announced with the outbreak of World War I during the campaign that under a Labor government, Australia would "stand beside the mother country to help and defend her to the last man and the last shilling."

The history of the Australian Labor Party has its origins in the Labour parties founded in the 1890s in the Australian colonies prior to federation. Labor tradition ascribes the founding of Queensland Labour to a meeting of striking pastoral workers under a ghost gum tree in Barcaldine, Queensland in 1891. The Balmain, New South Wales branch of the party claims to be the oldest in Australia. Labour as a parliamentary party dates from 1891 in New South Wales and South Australia, 1893 in Queensland, and later in the other colonies.

The 1917 Victorian state election was held in the Australian state of Victoria on Thursday 15 November 1917 for the state's Legislative Assembly. 51 of the 65 Legislative Assembly seats were contested.

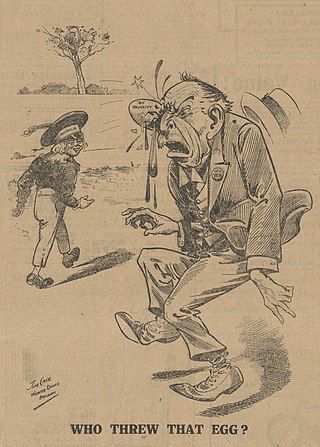

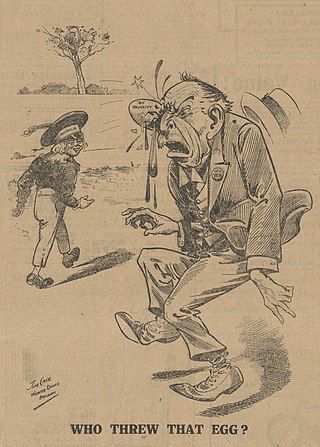

On 29 November 1917, an egg was thrown at the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes at the Warwick railway station, Queensland, during his campaign for the 1917 plebiscite on conscription. The egg was thrown by Patrick Michael Brosnan, possibly assisted by his brother Bartie Brosnan.

The Australian Labor Party split of 1916 occurred following severe disagreement within the Australian Labor Party over the issue of proposed World War I conscription in Australia. Labor Prime Minister of Australia Billy Hughes had, by 1916, become an enthusiastic supporter of conscription as a means to boost Australia's contribution to the war effort. On 30 August 1916, he announced plans for a referendum on the issue, and introduced enabling legislation into parliament on 15 September, which passed only with the support of the opposition. Six of Hughes's ministers resigned in protest at the move, and the New South Wales state branch of the Labor Party expelled Hughes. The referendum saw an intense campaign in which Labor figures vehemently advocated on each side of the argument, although the "no" campaign narrowly won on 14 November. In the wake of the referendum defeat, the caucus moved to expel Hughes on 14 November; instead, he and 23 supporters resigned and formed the National Labor Party. Frank Tudor was elected leader of the rump party. Hughes was recommissioned as Prime Minister, heading a minority government supported by the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party; the two parties then merged as the Nationalist Party of Australia and won the 1917 federal election. The Nationalist Party served as the main conservative party of Australia until 1931, and the split resulted in many early Labor figures ending their careers on the political right. Hughes, for instance, sat as a member of the Nationalists and their successors, the United Australia Party and the Liberal Party, with only a few short breaks until his death in 1952.

In November 1917 during World War I, the Australian Government conducted a raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office in Brisbane. The aim of the raid was to confiscate any copies of the Hansard, the official parliamentary transcript, which documented anti-conscription sentiments that had been aired in the state's parliament.