The Battle of Caporetto was a battle on the Italian front of World War I.

The 1st Army was a Royal Italian Army field army, in World War I, facing Austro-Hungarian and German forces, and in World War II, fighting on the North African front.

Marshal of Italy Luigi Cadorna, was an Italian general, Marshal of Italy and Count, most famous for being the Chief of Staff of the Italian Army from 1914 until 1917 during World War I. During this period he acquired a reputation for rigid discipline and the harsh treatment of his troops. Cadorna achieved successes at the battles of Asiago and Gorizia but, following a major defeat at the Battle of Caporetto in late 1917, he was relieved as Chief of Staff.

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto was fought from 24 October to 3 November 1918 near Vittorio Veneto on the Italian Front during World War I. After having thoroughly defeated Austro-Hungarian troops during the defensive Battle of the Piave River, the Italian army launched a great counter-offensive: the Italian victory marked the end of the war on the Italian Front, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and contributed to the end of the First World War just one week later. On 1 November, the new Hungarian government of Count Mihály Károlyi decided to recall all of the troops, who were conscripted from the territory of Kingdom of Hungary, which was a major blow for the Habsburg's armies. The battle led to the capture of over 5,000 artillery pieces and over 350,000 Austro-Hungarian troops, including 120,000 Germans, 83,000 Czechs and Slovaks, 60,000 South Slavs, 40,000 Poles, several tens of thousands of Romanians and Ukrainians, and 7,000 Austro-Hungarian loyalist Italians and Friulians.

The Sixth Battle of the Isonzo, better known as the Battle of Gorizia, was the most successful Italian offensive along the Soča (Isonzo) River during World War I.

Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union is the narrative of POWs from the Italian Army in Russia and of their fate in Stalin's Soviet Union during and after World War II.

The First Battle of the Isonzo was fought between the armies of Italy and Austria-Hungary on the northeastern Italian Front in World War I, between 23 June and 7 July 1915.

Luigi Capello was an Italian general, distinguished in both the Italo-Turkish War (1911–12) and World War I.

The Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo was a World War I battle fought by the Italian and Austro-Hungarian Armies on the Italian Front between 18 August and 12 September 1917.

Although a member of the Triple Alliance, Italy did not join the Central Powers – Germany and Austria-Hungary – when the war started with Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July 1914. In fact, the two Central Powers had taken the offensive while the Triple Alliance was supposed to be a defensive alliance. Moreover the Triple Alliance recognized that both Italy and Austria-Hungary were interested in the Balkans and required both to consult each other before changing the status quo and to provide compensation for whatever advantage in that area: Austria-Hungary did consult Germany but not Italy before issuing the ultimatum to Serbia, and refused any compensation before the end of the war.

The Seventh Battle of the Isonzo was fought from September 14–17, 1916 between the armies of the Kingdom of Italy and those of Austria-Hungary. It followed the Italian successes during the Trentino Offensive and the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo in the spring of 1916.

The Tenth Battle of the Isonzo was an Italian offensive against Austria-Hungary during World War I.

Events from the year 1917 in Italy.

The White War is the name given to the fighting in the high-altitude Alpine sector of the Italian front during the First World War, principally in the Dolomites, the Ortles-Cevedale Alps and the Adamello-Presanella Alps. More than two-thirds of this conflict zone lies at an altitude above 2,000m, rising to 3905m at Mount Ortler. In 1917 New York World correspondent E. Alexander Powell wrote: “On no front, not on the sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia, nor in the frozen Mazurian marshes, nor in the blood-soaked mud of Flanders, does the fighting man lead so arduous an existence as up here on the roof of the world.”

In Italy as in other countries the outbreak of the First World War created new opportunities and channels for propaganda. The unusual circumstances of Italy’s entry into the war meant that the government played no active role in propaganda work during the early years of the war. Public opinion was served by a pro-war nationalist press that avoided the unpleasant details of life on the front, while the army regarded discipline as more important than morale, leaving soldiers’ welfare to the Church. The momentous Italian defeat at Caporetto saw an end to this laissez-faire approach and the beginnings of a more centralised and managed effort to motivate the public and the army to the national cause.

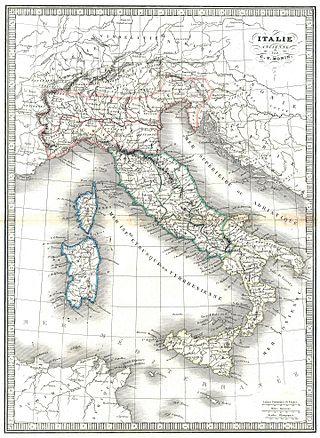

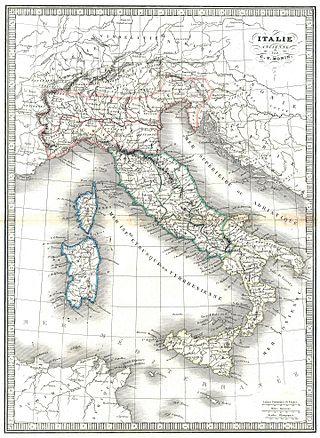

Between the 1860s and the First World War the Kingdom of Italy built a number of fortifications along its border with Austria-Hungary. From 1859 the fortified border ran south from Switzerland to Lake Garda, between Italian Lombardy and Austrian South Tyrol. After 1866 it extended to include the border between South Tyrol and Veneto, from Lake Garda to the Carnic Alps. This frontier was difficult to defend, since Austria-Hungary held the higher ground, and an invasion would immediately threaten the industrial and agricultural heartlands of the Po valley. Between 1900 and 1910, Italy also built a series of fortifications along the defensive line of the Tagliamento to protect against an invasion from the northeast. The border with Switzerland was also fortified in what is known as the Cadorna Line.

Roberto Brusati OSML OCI, was an Italian General of the Army who was an active participant in World War I. He was known for not having any military experience prior to the war and commanding the 1st Army before being dismissed from commanding the regiment on May 8, 1916, which was 8 days before the Battle of Asiago which was led by Field Marshal Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf.

Vittorio Italico Zupelli also known as Vittorio Zupelli, Vittorio Zuppelli and as Elio Vittorio Italico Zupelli was an Italian general and politician. He was the first Istrian to be appointed general of the Royal Italian Army and to hold the position of minister of the Kingdom of Italy. He as Minister of War twice, once when Italy entered the First World War, and again at the time of the armistice in 1918.

The Battle of Flondar, also known as the defeat of Flondar was a battle of the First World War, consisting of a counterattack launched by selected Austrian units under the command of General Svetozar Borojević against the Italian positions around the Monte Ermada. Although outnumbered, the Austro-Hungarians surprised the Italian defenses and, using new assault tactics, managed to reconquer some important positions, thus giving relief to their front lines.

About 8 million soldiers surrendered and were held in prisoner-of-war camps during World War I. All nations pledged to follow the Hague Conventions on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and the survival rate for POWs was generally, though not always, much higher than that of combatants at the front.