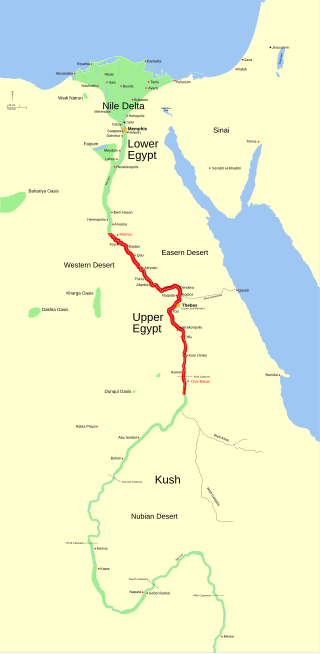

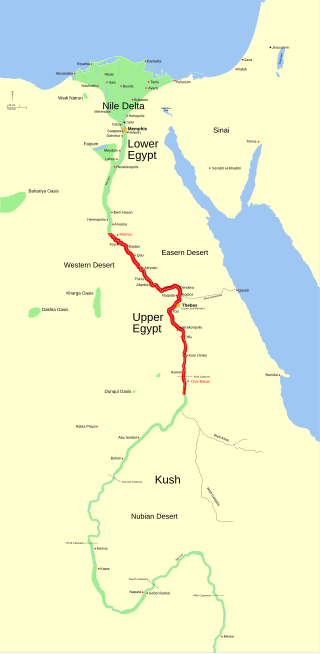

Upper Egypt is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel N. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake Nasser.

Nubians are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of civilization. In the southern valley of Egypt, Nubians differ culturally and ethnically from Egyptians, although they intermarried with members of other ethnic groups, especially Arabs. They speak Nubian languages as a mother tongue, part of the Northern Eastern Sudanic languages, and Arabic as a second language.

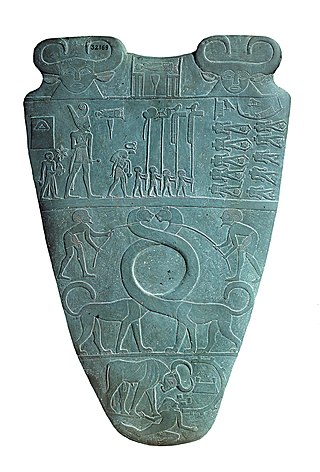

The First Dynasty of ancient Egypt covers the first series of Egyptian kings to rule over a unified Egypt. It immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, by Menes, or Narmer, and marks the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, when power was centered at Thinis.

The Early Dynastic Period, also known as Archaic Period or the Thinite Period, is the era of ancient Egypt that immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in c. 3150 BC. It is generally taken to include the First Dynasty and the Second Dynasty, lasting from the end of the archaeological culture of Naqada III until c. 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom. With the First Dynasty, the Egyptian capital moved from Thinis to Memphis, with the unified land being ruled by an Egyptian god-king. In the south, Abydos remained the major centre of ancient Egyptian religion; the hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilization, such as Egyptian art, Egyptian architecture, and many aspects of Egyptian religion, took shape during the Early Dynastic Period.

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt was the period of time starting at the first human settlement and ending at the First Dynasty of Egypt around 3100 BC.

Lower Nubia is the northernmost part of Nubia, roughly contiguous with the modern Lake Nasser, which submerged the historical region in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Many ancient Lower Nubian monuments, and all its modern population, were relocated as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia; Qasr Ibrim is the only major archaeological site which was neither relocated nor submerged. The intensive archaeological work conducted prior to the flooding means that the history of the area is much better known than that of Upper Nubia. According to David Wengrow, the A-Group Nubian polity of the late 4th millenninum BCE is poorly understood since most of the archaeological remains are submerged underneath Lake Nasser.

The Kingdom of Kerma or the Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia", and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt. The polity seems to have been one of a number of Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700 to 1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Sai and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt. Around 1500 BC, it was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. By the eleventh century BC, the more-Egyptianized Kingdom of Kush emerged, possibly from Kerma, and regained the region's independence from Egypt.

The Badarian culture provides the earliest direct evidence of agriculture in Upper Egypt during the Predynastic Era. It flourished between 4400 and 4000 BC, and might have already emerged by 5000 BC.

Hedjet is the White Crown of pharaonic Upper Egypt. After the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, it was combined with the Deshret, the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, to form the Pschent, the double crown of Egypt. The symbol sometimes used for the White Crown was the vulture goddess Nekhbet shown next to the head of the cobra goddess Wadjet, the uraeus on the Pschent.

Nobatia or Nobadia was a late antique kingdom in Lower Nubia. Together with the two other Nubian kingdoms, Makuria and Alodia, it succeeded the kingdom of Kush. After its establishment in around 400, Nobadia gradually expanded by defeating the Blemmyes in the north and incorporating the territory between the second and third Nile cataract in the south. In 543, it converted to Coptic Christianity. It would then be annexed by Makuria, under unknown circumstances, during the 7th century.

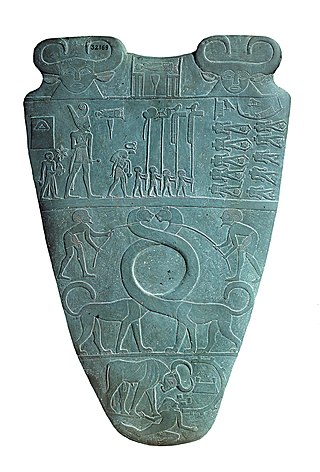

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating from approximately 3200 to 3000 BC. It is the period during which the process of state formation, which began in Naqada II, became highly visible, with named kings heading powerful polities. Naqada III is often referred to as Dynasty 0 or the Protodynastic Period to reflect the presence of kings at the head of influential states, although, in fact, the kings involved would not have been a part of a dynasty. In this period, those kings' names were inscribed in the form of serekhs on a variety of surfaces including pottery and tombs.

The A-Group was the first powerful society in Nubia, located in modern southern Egypt and northern Sudan that flourished between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Lower Nubia. It lasted from the 4th millennium BC, reached its climax at c. 3100 BC, and fell 200 years later c. 2900 BC.

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt, named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. A 2013 Oxford University radiocarbon dating study of the Predynastic period suggests a beginning date sometime between 3,800 and 3,700 BC.

Ballana was a cemetery in Lower Nubia. It, along with nearby Qustul, were excavated by Walter Bryan Emery between 1928 and 1931 as a rescue project before a second rising of the Aswan Low Dam. A total of 122 tombs were found under huge artificial mounds. They date to the time after the collapse of the Meroitic state but before the founding of the Christian Nubian kingdoms, around AD 350 to 600. They usually featured one or several underground chambers, with one main burial chamber. Some tombs were found unlooted, but even the robbed burials still proved to contain many burial goods.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, and the area between the first cataract of the Nile or more strictly, Al Dabbah. It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

The Kingdom of Kush, also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

Egypt has a long and involved demographic history. This is partly due to the territory's geographical location at the crossroads of several major cultural areas: North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, Egypt has experienced several invasions and being part of many regional empires during its long history, including by the Canaanites, the Ancient Libyans, the Assyrians, the Kushites, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, and the Arabs.

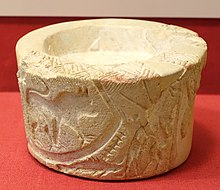

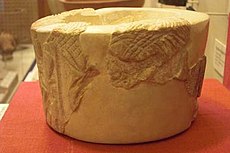

The Tasian culture is possibly one of the oldest-known Predynastic culture in Upper Egypt, which evolved around 4500 BC. It is named for the burials found at Deir Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile located between Asyut and Akhmim. There is no general agreement about the proposed "Tasian culture", and some scholars since Baumgartel in 1955 have suggested it is a part of the Badarian culture, rather than a separate entity.

The X-Group Culture was an ancient Nubian civilization that existed in Lower Nubia. Cemetery excavations revealed that the civilization stretched from the Dodekaschoinos in the north to Delgo in the south.

Kushite religion is the traditional belief system and pantheon of deities associated with the Ancient Kushites, who founded the Kingdom of Kush in the land of Nubia in present-day Sudan.