Pedro Albizu Campos was a Puerto Rican attorney and politician, and a leading figure in the Puerto Rican independence movement. He was the president and spokesperson of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico from 1930 until his death. He led the nationalist revolts of October 1950 against the United States government in Puerto Rico. Albizu Campos spent a total of twenty-six years in prison at various times for his Puerto Rican independence activities.

The 1954 United States Capitol shooting was an attack on March 1, 1954, by four Puerto Rican nationalists seeking to promote Puerto Rican independence from the United States. They fired 30 rounds from semi-automatic pistols onto the legislative floor from the Ladies' Gallery of the House of Representatives chamber within the United States Capitol.

Lolita Lebrón was a Puerto Rican nationalist who was convicted of aggravated assault and other crimes after carrying out an armed attack on the United States Capitol in 1954, which resulted in the wounding of five members of the United States Congress. She was released from prison in 1979 after being granted clemency by President Jimmy Carter. Lebrón was born and raised in Lares, Puerto Rico, where she joined the Puerto Rican Liberal Party. In her youth she met Francisco Matos Paoli, a Puerto Rican poet, with whom she had a relationship. In 1941, Lebrón migrated to New York City, where she joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, gaining influence within the party's leadership.

The Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico is a Puerto Rican political party founded on September 17, 1922, in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Its primary goal is to work for Puerto Rico's independence. The Party's selection in 1930 of Pedro Albizu Campos as its president brought a radical change to the organization and its tactics.

Olga Isabel Viscal Garriga was a public orator and political activist. Born in Brooklyn, New York, she moved to Puerto Rico, where she was a student leader and spokesperson of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party's branch in Rio Piedras. As an advocate for Puerto Rican independence, she was sentenced to eight years in a U.S. federal penitentiary, for refusing to recognize the sovereign authority of the United States over Puerto Rico.

Blanca Canales was an educator and a Puerto Rican Nationalist. Canales joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party in 1931 and helped organize the Daughters of Freedom, the women's branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.

The Jayuya Uprising, also known as Jayuya Revolt or Cry of Jayuya, was a Nationalist insurrection that took place on October 30, 1950, in the town of Jayuya, Puerto Rico. The insurrection, led by Blanca Canales, was one of the multiple insurrections that occurred throughout Puerto Rico on that day against the Puerto Rican government supported by the United States. The insurrectionists were opposed to US sovereignty over Puerto Rico.

Oscar Collazo was one of two Puerto Rican militants of the Nationalist Party who on November 1, 1950, attempted to assassinate U.S. President Harry S. Truman in Washington, D.C. He had been living in New York City after growing up in Puerto Rico.

Rosa Collazo a.k.a. Rosa Cortez-Collazo was a political activist and treasurer of the New York City branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. She was the wife of Oscar Collazo one of two Nationalists who attacked Blair House in 1950 in an attempt to kill President Harry Truman. She was accused by the FBI of assisting Nationalists Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Irvin Flores and Andres Figueroa Cordero in their assault on the United States House of Representatives in 1954. She was charged on both occasions with seditious conspiracy for her complicity in a conspiracy to overthrow the United States Government and imprisoned because of her political beliefs.

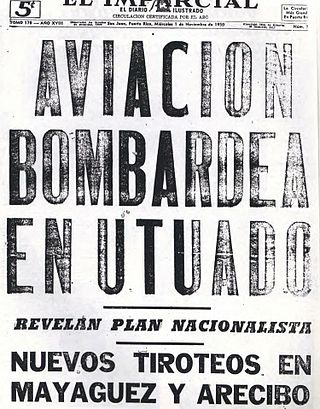

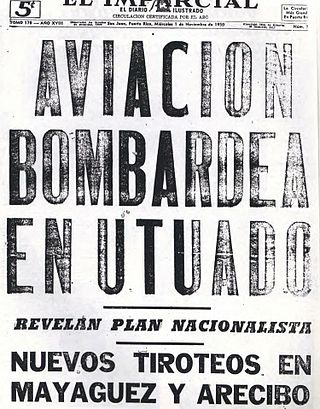

The Utuado uprising, also known as the Utuado revolt or El Grito de Utuado, refers to the revolt against the United States government in Puerto Rico which occurred on October 30, 1950, in the town of Utuado. There were simultaneous revolts in various other towns in Puerto Rico, including the capital of San Juan and the cities of Mayaguez and Arecibo, plus major confrontations in the city of Ponce and the towns of Peñuelas and Jayuya.

The San Juan Nationalist revolt was one of many uprisings against United States Government rule which occurred in Puerto Rico on October 30, 1950 during the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts. Amongst the uprising's main objectives were an attack on La Fortaleza, and the U.S. Federal Court House Building in Old San Juan.

The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party insurgency was a series of coordinated insurrections for the secession of Puerto Rico led by the president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, against the United States government's rule over the islands of Puerto Rico. The party repudiated the "Free Associated State" status that had been enacted in 1950 and which the Nationalists considered a continuation of colonialism.

Alberto Rodriguez was a Puerto Rican member of the FALN who received a sentence of 35 years for seditious conspiracy and other charges. He was sentenced in 1985, and incarcerated first at United States Penitentiary in Lewisburg, PA, and later at the federal penitentiary at USP Beaumont, TX. However, he was released early from prison, after President Bill Clinton extended a clemency offer in August 1999. Alberto and 10 other Puerto Rican prisoners were released on September 10, 1999.

Isolina Rondón was a political activist. She was one of the few witnesses of the killing of four Nationalists committed by local police officers in Puerto Rico during a confrontation with the supporters of the Nationalist Party that occurred on October 24, 1935, and which is known as the Río Piedras massacre. Rondón joined the political movement and became the Treasurer of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party which staged various uprisings in Puerto Rico against the colonial Government of the United States in 1950.

Isabel Rosado, also known as Doña Isabelita, was an educator, social worker, activist and member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Influenced by the events of the Ponce massacre, Rosado became a believer of the Puerto Rican independence movement and was imprisoned because of her commitment to the cause.

Ruth Mary Reynolds was an American educator, political and civil rights activist who embraced the ideals of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. She was incarcerated in La Princesa Prison for sedition during the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s. As one of the founders of the organization known as the "American League for Puerto Rico's Independence," she devoted many years of her life to the cause of Puerto Rico's independence from the United States after her release from prison.

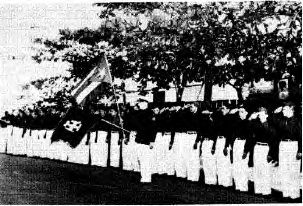

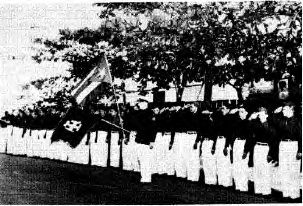

Raimundo Díaz Pacheco was a political activist and the Treasurer General of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He was also commander-in-chief of the Cadets of the Republic, the official youth organization within the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. This quasi-military organization was also known as the Ejército Libertador de Puerto Rico.

Law 53 of 1948 better known as the Gag Law, was an act enacted by the Puerto Rico legislature of 1948, with the purpose of suppressing the independence movement in Puerto Rico. The act made it a crime to own or display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to speak or write of independence, or to meet with anyone or hold any assembly in favor of Puerto Rican independence. It was passed by a legislature that was overwhelmingly dominated by members of the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), which supported developing an alternative political status for the island. The bill was signed into law on June 10, 1948 by Jesús T. Piñero, the United States-appointed governor. Opponents tried but failed to have the law declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court.

Irvin Flores was a political activist, member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and an advocate of Puerto Rican independence. Flores was a leader of the Nationalist faction of Mayagüez, Puerto Rico during the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s. On March 1, 1954, Flores together with fellow Nationalists Lolita Lebrón, Andrés Figueroa Cordero, and Rafael Cancel Miranda entered the United States Capitol building armed with automatic pistols and fired 30 shots. Five Congressmen were wounded, however all the representatives survived and Flores, along with the other three members of his group were immediately arrested.

Andrés Figueroa Cordero was a political activist, member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and an advocate of Puerto Rican independence. On March 1, 1954, with fellow Nationalists Lolita Lebrón, Irvin Flores, and Rafael Cancel Miranda, he entered the United States Capitol building armed with automatic pistols; thirty shots were fired. Five congressmen were wounded but all survived. Figueroa Cordero, along with the other three members of his group, was immediately arrested.