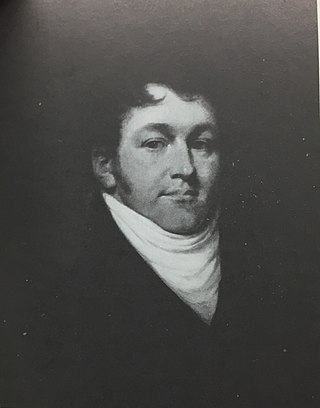

Sampson Salter Blowers was a noted North American lawyer, Loyalist and jurist from Nova Scotia who, along with Chief Justice Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange, waged "judicial war" in his efforts to free Black Nova Scotian slaves from their owners, leading to the decline of slavery in Nova Scotia.

Slavery in Canada includes historical practices of enslavement practised by both the First Nations until the latter half of the 19th century, and by colonists during the period of European colonization.

Joseph Howe was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, public servant, and poet. Howe is often ranked as one of Nova Scotia's most admired politicians and his considerable skills as a journalist and writer have made him a provincial legend.

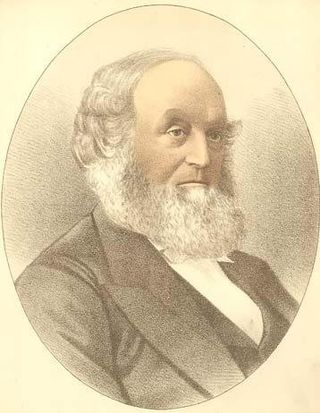

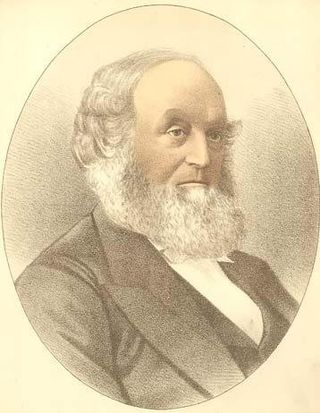

Sir William Young, was a Nova Scotia politician and jurist.

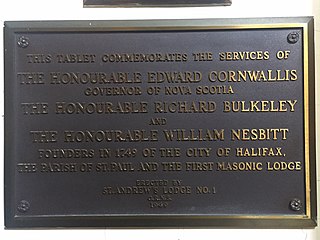

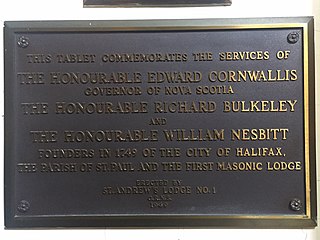

St. Paul's Church is a historically evangelical Anglican church in downtown Halifax, Nova Scotia, within the Diocese of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island of the Anglican Church of Canada. It is located at the south end of the Grand Parade, an open square in downtown Halifax with Halifax City Hall at the northern end.

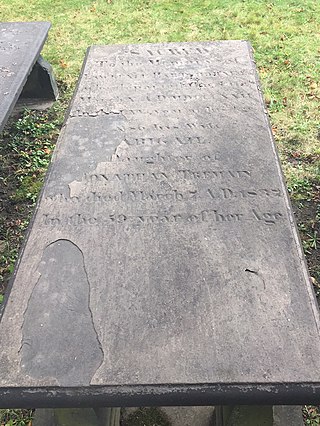

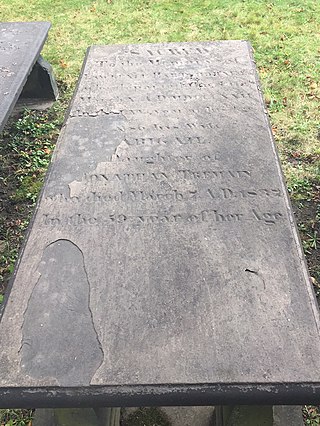

The Old Burying Ground is a historic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located at the intersection of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road in Downtown Halifax.

The history of Nova Scotia covers a period from thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Nova Scotia were inhabited by the Mi'kmaq people. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the region was claimed by France and a colony formed, primarily made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This time period involved six wars in which the Mi'kmaq along with the French and some Acadians resisted British control of the region: the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, the capital was moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, to the newly established Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749). The warfare ended with the Burying the Hatchet ceremony (1761). After the colonial wars, New England Planters and Foreign Protestants immigrated to Nova Scotia. After the American Revolution, Loyalists immigrated to the colony. During the nineteenth century, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848 and joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

Black Nova Scotians are Black Canadians whose ancestors primarily date back to the Colonial United States as slaves or freemen, later arriving in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the 18th and early 19th centuries. As of the 2021 Census of Canada, 28,220 Black people live in Nova Scotia, most in Halifax. Since the 1950s, numerous Black Nova Scotians have migrated to Toronto for its larger range of opportunities. The first recorded free African person in Nova Scotia, Mathieu da Costa, a Mikmaq interpreter, was recorded among the founders of Port Royal in 1604. West Africans escaped slavery by coming to Nova Scotia in early British and French Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many came as enslaved people, primarily from the French West Indies to Nova Scotia during the founding of Louisbourg. The second major migration of people to Nova Scotia happened following the American Revolution, when the British evacuated thousands of slaves who had fled to their lines during the war. They were given freedom by the Crown if they joined British lines, and some 3,000 African Americans were resettled in Nova Scotia after the war, where they were known as Black Loyalists. There was also the forced migration of the Jamaican Maroons in 1796, although the British supported the desire of a third of the Loyalists and nearly all of the Maroons to establish Freetown in Sierra Leone four years later, where they formed the Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.

The Book of Negroes is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during the American Revolution and were evacuated to points in Nova Scotia as free people of colour.

Black refugees were black people who escaped slavery in the United States during the War of 1812 and settled in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Trinidad. The term is used in Canada for those who settled in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. They were the most numerous of the African Americans who sought freedom during the War of 1812. The Black refugees were the third group of African Americans, after the Black Loyalists, to flee American enslavement in wartime and settle in Canada. They make up the most significant single immigration source for today's African Nova Scotian communities. During the antebellum period, however, an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 Black refugees reached freedom in Canada, often traveling alone or in small family groups.

Samuel George William Archibald was a lawyer, judge and political figure in Nova Scotia. He represented Halifax County from 1806 to 1836 and Colchester County from 1836 to 1841 in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly. He supported the Royal Acadian School.

Richard John Uniacke was a lawyer, judge and political figure in Nova Scotia. He represented Cape Breton County in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1820 to 1830.

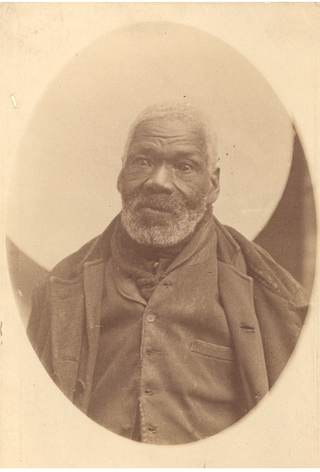

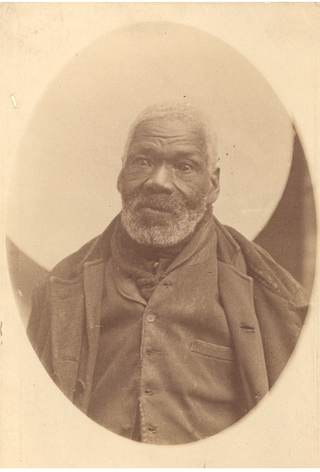

Moses "Daddy Moses" Wilkinson or "Old Moses" was an American Wesleyan Methodist preacher and Black Loyalist. His ministry combined Old Testament divination with African religious traditions such as conjuring and sorcery. He gained freedom from slavery in Virginia during the American Revolutionary War and was a Wesleyan Methodist preacher in New York and Nova Scotia. In 1791, he migrated to Sierra Leone, preaching alongside ministers Boston King and Henry Beverhout. There, he established the first Methodist church in Settler Town and survived a rebellion in 1800.

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers, were African Americans and African Nova Scotians or Black Canadians of African-American descent who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792. The majority of these black American immigrants were among 3,000 African Americans, mostly former slaves, who had sought freedom and refuge with the British during the American Revolutionary War, leaving rebel masters. They became known as the Black Loyalists. The Nova Scotian Settlers were jointly led by African American Thomas Peters, a former soldier, and English abolitionist John Clarkson. For most of the 19th century, the Settlers resided in Settler Town and remained a distinct ethnic group within the Freetown territory, tending to marry among themselves and with Europeans in the colony.

William Nesbitt was a lawyer and political figure in Nova Scotia. He served as a member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1758 to 1783.

Andrew Mitchell Uniacke was a lawyer, banker and politician in Nova Scotia. He represented Halifax township in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1843 to 1847.

Jonathan Sterns was a Loyalist from Boston, Solicitor General for Nova Scotia and political figure in Nova Scotia. He represented Halifax County in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1793 to 1798.

Uniacke Estate Museum Park is the historic home and preserved estate of Richard John Uniacke at Mount Uniacke (c.1813). The Uniacke Estate is part of the Nova Scotia Museum system.

William Bowie (1762-1819) was a prominent merchant of Halifax, Nova Scotia who was killed in the last fatal duel on record in Nova Scotia. At age 20, William Bowie arrived in Nova Scotia in 1782 from Stirling, Scotland, the son of Alexander Bowie and Janet Murdoch. He became president of the North British Society. Under the mentorship of Alexander Brymer, Bowie founded the firm Bowie & DeBlois and in a few years amassed a fortune and Bowie became a leading citizen in Halifax.