Early life

Detrosier's parents were Manchester merchant Robert Norris and a French woman named Detrosier. He was born in London but was abandoned. He was then adopted by Charles Barnes, a Swedenborgian tailor who raised him in Hulme, Manchester. Barnes treated him as his own son and named him Rowley. [1]

Before he started work aged nine, Detrosier had received only informal education, including that from the Manchester Benevolent Vegetarian Institute. He worked in a variety of menial jobs and married aged nineteen but managed to teach himself something of French, Latin, mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, botany, and geology. His appetite for learning reduced Detrosier to dire financial straits by 1821 and he was only rescued by the patronage of John Shuttleworth, who found him a more secure and responsible job as a clerk and salesman. At this time, he also discovered his birth parentage. [1]

Radical

In March 1829, Detrosier led a break-away from the Manchester Mechanics' Institute, which he considered to be undemocratic, and established the New Mechanics' Institution. [2] John Doherty sought his help in establishing trade unions but Detrosier was no socialist, believing that democracy posed real dangers unless individual moral development preceded political freedom. [1]

Detrosier attracted the further patronage of Francis Place who established him as a full-time lecturer. Shuttleworth arranged for the 1831 publication of On the Necessity of an Extension of Moral and Political Instruction among the Working Classes and his work attracted the attention of Jeremy Bentham and Anne Isabella Byron, Baroness Byron. In 1831, Detrosier became secretary of the National Political Union whereby he became friends with John Stuart Mill and met Thomas Carlyle, Gustave d'Eichtal, George Birkbeck, and John Arthur Roebuck. Detrosier's new position in the liberal political establishment led him to work with health campaigner Thomas Southwood Smith. [1]

Detrosier lectured on meteorology and pneumatics at the London Mechanics' Institute but was dismissed when he acted as interpreter for Gregorio Fontana and Gioacchino Prati's campaign in England in 1833. [3] However, he found a new sponsor in Robert Mordan and Detrosier made a living lecturing and writing. In 1834, he contracted a common cold and died at his home in London. He left his body to science. [1]

Abel Heywood was an English publisher, radical and mayor of Manchester.

Robert Vaughan (1795–1868) was an English minister of the Congregationalist communion, academic, college head and writer, from a Welsh background. He was professor of history in the London University, and then president of the Independent College, Manchester. He founded, and for a time edited, the British Quarterly.

Richard Watson (1781–1833) was a British Methodist theologian, a leading figure of Wesleyan Methodism in the early 19th century.

Rowland Hill A.M. was a popular English preacher, enthusiastic evangelical and an influential advocate of smallpox vaccination. He was founder and resident pastor of a wholly independent chapel, the Surrey Chapel, London; chairman of the Religious Tract Society; and a keen supporter of the British and Foreign Bible Society and the London Missionary Society. The famous instigator of penny postage, Rowland Hill, is said to have been christened 'Rowland' after him.

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative movement. The Owenite movement undertook several experiments in the establishment of utopian communities organized according to communitarian and cooperative principles. One of the best known of these efforts, which were largely unsuccessful, was the project at New Harmony, Indiana, which started in 1825 and was abandoned by 1829. Owenism is also closely associated with the development of the British trade union movement, and with the spread of the Mechanics' Institute movement.

Henry Hetherington was an English printer, bookseller, publisher and newspaper proprietor who campaigned for social justice, a free press, universal suffrage and religious freethought. Together with his close associates, William Lovett, John Cleave and James Watson, he was a leading member of numerous co-operative and radical groups, including the Owenite British Association for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge, the National Union of the Working Classes and the London Working Men's Association. As proprietor of The Poor Man's Guardian he played a major role in the "War of the Unstamped" and was imprisoned three times for refusing to pay newspaper stamp duty. He was a leader of the "moral force" wing of the Chartist movement and a supporter of pro-democracy movements in other countries. His name is included on the Reformers' Memorial in Kensal Green Cemetery.

William Gaskell was an English Unitarian minister, charity worker and pioneer in the education of the working class. The husband of novelist and biographer Elizabeth Gaskell, he was himself a writer and poet, and acted as the longest-serving Chair of the Portico Library from 1849 to his death in 1884.

The Royal Victoria Gallery for the Encouragement of Practical Science was an adult education institution and exhibition gallery in Victorian Manchester, a commercial enterprise intended to educate the general public about science and its industrial applications.

Sir Thomas Potter was an English industrialist and Liberal politician, and the first Mayor of Manchester.

Joseph Brotherton was a reforming British politician, Nonconformist minister and pioneering vegetarian. He has been described as the first vegetarian member of parliament.

Edward Brotherton (1814–1866) was an English Swedenborgian and a campaigner for educational reform.

Louisa Mary Barwell (1800–1885) was an English musician and educational writer.

Absalom Watkin (1787–1861), was an English social and political reformer, an anti corn law campaigner, and a member of Manchester's Little Circle that was key in passing the Reform Act 1832.

The Little Circle was a Manchester-based group of Non-conformist Liberals, mostly members of the Portico Library, who held a common agenda with regards to political and social reform. The first group met from 1815 onwards to campaign for expanded political representation and gain social reform in the United Kingdom. The second group operated from 1830 onwards and was key in creating the popular movement that resulted in the Reform Act 1832.

Richard Potter (1778–1842) was a radical non-conformist Liberal Party MP for Wigan, and a founding member of the Little Circle which was key in gaining the Reform Act 1832.

Elijah Dixon was a textile worker, businessman, and agitator for social and political reform from Newton Heath, Manchester, England. He was prominent in the 19th century Reform movement in industrial Lancashire, and an associate of some of its leading figures, including Ernest Jones, and his obituary claims that he was called "the Father of English Reformers". His activism led to arrest and detention for suspected high treason, alongside some other leading figures of the movement, and he was present at key events including the Blanketeers' March and the Peterloo massacre. In later life he became a successful and wealthy manufacturer. He was the uncle of William Hepworth Dixon.

John James Tayler (1797–1869) was an English Unitarian Minister.

John Clowes was an English cleric and Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. Despite his position in the Anglican church, for which he served as Rector of St John's Church, Manchester from 1769 until 1831, he was a noted disciple of Emanuel Swedenborg and did much to propagate his ideas in the Manchester area.

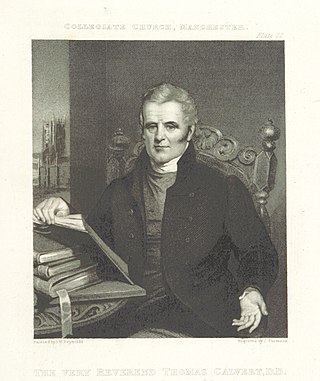

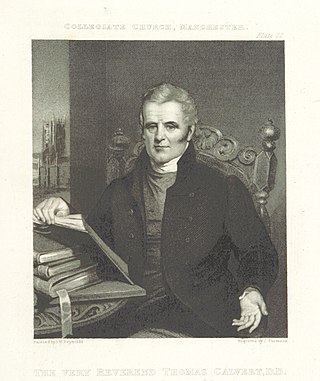

Thomas Jackson Calvert (1775–1840) was an English Anglican priest and theologian. Calvert was born in 1775; educated at Kirkham Grammar School and St John's College, Cambridge; and ordained in 1800. He held incumbencies at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor and Manchester Collegiate Church. He was Norrisian Professor of Divinity from 1815 to 1824. He died on 4 June 1840.

The Lincoln Mechanics' Institute or Lincoln and Lincolnshire Mechanics' Institute was founded in Lincoln, England in 1833. It was one of the many Mechanics' institutes which sprang up in the early 19th century and was the first Mechanics' Institute to be founded in Lincolnshire.