The Abu Nidal Organization, officially Fatah – Revolutionary Council, was a Palestinian militant group founded by Abu Nidal in 1974. It broke away from Fatah, a faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization, following the emergence of a rift between Abu Nidal and Yasser Arafat. The ANO was designated as a terrorist organization by Israel, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the European Union and Japan. However, a number of Arab countries supported the group's activities; it was backed by Iraq from 1974 to 1983, by Syria from 1983 to 1987, and by Libya from 1987 to 1997. It briefly cooperated with Egypt from 1997 to 1998, but ultimately returned to Iraq in December 1998, where it continued to have the state's backing until Abu Nidal's death in August 2002.

Fatah, formally the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist and social democratic political party. It is the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the second-largest party in the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC). Mahmoud Abbas, the President of the Palestinian Authority, is the chairman of Fatah.

The Palestine Liberation Organization is a Palestinian nationalist coalition that is internationally recognized as the official representative of the Palestinian people in both the Palestinian territories and the diaspora. It is currently represented by the Palestinian Authority based in the West Bank city of Al-Bireh.

Palestinians hold a diverse range of views on the peace process with Israel, though the goal that unites them is the end of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. Some Palestinians accept a two-state solution, with the West Bank and the Gaza Strip forming a distinct Palestinian state, whereas other Palestinians insist on a one-state solution with equal rights for all citizens whether they are Muslims, Christians or Jews. In this scenario, Palestinian refugees may be allowed to resettle the land they were forced to flee in the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight. However, widespread anti-Semitic sentiments in Palestinian society and Palestinian militancy have hindered the peace process.

Yasser Arafat, also popularly known by his kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, President of the State of Palestine from 1989 to 2004 and President of the Palestinian Authority (PNA) from 1994 to 2004. Ideologically an Arab nationalist and a socialist, Arafat was a founding member of the Fatah political party, which he led from 1959 until 2004.

The Black September Organization (BSO) was a Palestinian militant organization founded in 1970. Besides other actions, the group was responsible for the assassination of the Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Tal, and the Munich massacre, in which eleven Israeli athletes and officials were kidnapped and killed, as well as a West German policeman dying, during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, their most publicized event. These attacks led to the creation or specialization of permanent counter-terrorism forces in many European countries.

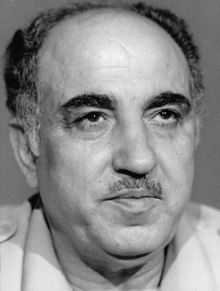

Sabri Khalil al-Banna, known by his nom de guerreAbu Nidal, was a Palestinian militant. He was the founder of Fatah: The Revolutionary Council, a militant Palestinian splinter group more commonly known as the Abu Nidal Organization (ANO). Abu Nidal formed the ANO in October 1974 after splitting from Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The Palestinian Liberation Front, also known as the Palestine Liberation Front - Abu Abbas Faction or Palestine Liberation Front, is a minor left-wing Palestinian political faction. Since 1997, the PLF has been a designated terrorist organization by the United States and by Canada since 2003. The PLF has also been banned in Japan.

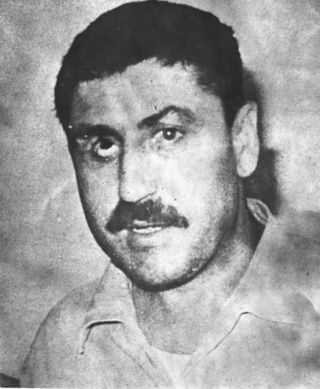

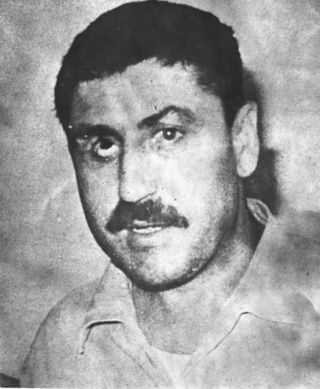

Khalil Ibrahim al-Wazir was a Palestinian leader and co-founder of the nationalist party Fatah. As a top aide of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat, al-Wazir had considerable influence in Fatah's military activities, eventually becoming the commander of Fatah's armed wing al-Assifa.

The Rejectionist Front or Front of the Palestinian Forces Rejecting Solutions of Surrender was a political coalition formed in 1974 by radical Palestinian factions who rejected the Ten Point Program adopted by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in its 12th Palestinian National Congress (PNC) session.

Hani al Hassan, also known as Abu Tariq and Abu-l-Hasan, was a leader of the Fatah organization in Germany and member of the Palestinian Authority Cabinet and the Palestinian National Council.

Khaled al-Hassan was an early adviser of Yasser Arafat, PLO leader and a founder of the Palestinian political and militant organization Fatah. Khaled was the older brother of Hani al-Hassan.

Walid Ahmad Nimr, better known by his nom de guerreAbu Ali Iyad, was a Palestinian militant and senior paramilitary field commander based in Syria and Jordan during the 1960s and early 1970s.

Issam Sartawi was a senior member of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). He is remembered for his "moderate" stance within the PLO and his participation in dialogues with Israeli counterparts.

The Fatah Central Committee is the highest decision-making body of the Palestinian organization and political party, Fatah.

Fakhri Al Omari, known as Abu Muhammad, was a Palestinian who was a member of the Fatah movement. He was an aide of Salah Khalaf. They were assassinated by the Abu Nidal Organization in Tunisia on 14 January 1991.

Hayel Abdul Hamid, known as Abu al Hol, was a Palestinian who was a member of the Fatah. He served in its different agencies and was its security head. He was assassinated at his home in Carthage, Tunisia, on 14 January 1991 along with other Fatah members, Salah Khalaf and Fakhri Al Omari.

Assad Saftawi (1935–1993) was a Palestinian cofounder and leader of the Fatah movement who was shot to death by three masked hitmen in the Gaza Strip on 21 October 1993. The assassination remains unsolved.

Events in the year 1991 in Palestine.