The early history of Cambodia follows the prehistoric and protohistoric development of Cambodia as a country in mainland Southeast Asia. Thanks to archaeological work carried out since 2009, this can now be traced back to the Neolithic period. As excavation sites have become more numerous and modern dating methods are applied, settlement traces of all stages of human civil development from neolithic hunter-gatherer groups to organized preliterate societies are documented in the region.

The Miami Circle, also known as The Miami River Circle, Brickell Point, or The Miami Circle at Brickell Point Site, is an archaeological site in Brickell, Miami, Florida. It consists of a perfect circle measuring 38 feet (11.5m) of 600 postmolds that contain 24 holes or basins cut into the limestone bedrock, on a coastal spit of land, surrounded by a large number of other 'minor' holes. It predates other known permanent settlements on the East Coast. It is believed to have been the location of a structure, built by the Tequesta Indians, in what was possibly their capital. Discovered in 1998, the site is believed to be somewhere between 1,700 and 2,000 years old.

The Japanese Paleolithic period is the period of human inhabitation in Japan predating the development of pottery, generally before 10,000 BC. The starting dates commonly given to this period are from around 40,000 BC, with recent authors suggesting that there is good evidence for habitation from c. 36,000 BC onwards. The period extended to the beginning of the Mesolithic Jōmon period, or around 14,000 BC.

Niah National Park, located within Miri Division, Sarawak, Malaysia, is the site of the Niah Caves which are an archeological site.

Ban Non Wat is a village in Thailand, in the Non Sung district, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, located near the small city of Phimai. It has been the subject of excavation since 2002. The cultural sequence encompasses 11 prehistoric phases, which include 640 burials. The site is associated with consistent occupation, and in modern-day Ban Non Wat the occupied village is located closer to the Mun River.

Devil's Lair is a single-chamber cave with a floor area of around 200 m2 (2,200 sq ft) that formed in a Quaternary dune limestone of the Leeuwin–Naturaliste Ridge, 5 km (3.1 mi) from the modern coastline of Western Australia. The stratigraphic sequence in the cave floor deposit consists of 660 cm (260 in) of sandy sediments, with more than 100 distinct layers, intercalated with flowstone and other indurated deposits. Excavations have been made in several areas of the cave floor. Since 1973, excavations have been concentrated in the middle of the cave, where 10 trenches have been dug. Archaeological evidence for intermittent human occupation extends down about 350 cm (140 in) to layer 30, with hearths, bone, and stone artefacts found throughout. The site provides evidence of human habitation of Southwest Australia 50,000 years before the present day.

Prehistoric Thailand may be traced back as far as 1,000,000 years ago from the fossils and stone tools found in northern and western Thailand. At an archaeological site in Lampang, northern Thailand Homo erectus fossils, Lampang Man, dating back 1,000,000 – 500,000 years, have been discovered. Stone tools have been widely found in Kanchanaburi, Ubon Ratchathani, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Lopburi. Prehistoric cave paintings have also been found in these regions, dating back 10,000 years.

The Con Moong cave is located in the Cúc Phương National Park, just south of Mọ village, in the Thanh Hóa Province, northern Vietnam. The Department of Culture has issued a certificate that declares Con Moong prehistoric site and its surroundings as National Relics and is managed by the Cúc Phương National Park administration, along with a refuge for rare animals. Among these locations, the archaeological site of Con Moong cave is of central importance for the study of the Mesolithic Hoabinhian culture. In April and May 1976, Vietnamese archaeologists excavated the site.

Archeological sites in Azerbaijan first gained public interest in the mid-19th century and were reported by European travellers.

The Hong Kong Archaeological Society is a government-funded organization dedicated to carrying out excavations and preserving archaeological heritage in Hong Kong. The society is affiliated with the Hong Kong Museum of History to establish artifact collections and journal publications.

Chinit River is a river of Cambodia. Located in Kampong Thom Province, it is a major tributary of the Tonlé Sap Lake, which joins the Tonlé Sap River at the downstream end in the larger Mekong basin. Somewhat unusually the river is looped back into the same river system, which accounts for its length of 264 kilometres (164 mi), leaving Tonlé Sap lake and entering its river again downstream. The prehistoric archaeological site of Samrong Sen is located on the river bank. Water resource projects, commencing in 1971 and in 2003, have had various measures of success. The river is an important trade route.

Phum Snay is an Iron Age archaeological site discovered in May 2000 in Preah Neat Prey District, Banteay Meanchey Province, Northwest Cambodia, around 80 km (50 mi) from the temple ruins of Angkor. The site was excavated between 2001 and 2003 by primary excavators Dougald O’Reilly of the Australian National University, Pheng Sitha and Thuy Chanthourn. The excavation was intended to discover more about Iron Age life in Cambodia.

Dewil Valley, located in the northernmost part of Palawan, an island province of the Philippines that is located in the Mimaropa region, is an archaeological site composed of thousands of artifacts and features. According to the University of the Philippines Archaeological Studies Program, or UP-ASP, the closest settlement can be found in New Ibajay, which is covered by the town capital of El Nido, which is located around 9 km (5.6 mi) south-east of Dewil Valley. Physically it measures around 7 km (4.3 mi) long, and 4 km (2.5 mi) wide. It is in this place which the Ille Cave, one of the main archaeological sites, can be found. It is actually a network of 3 cave mouths located at its base. It has been discovered that this site in particular has been used and occupied by humans over multiple time periods.

Ban Kao is a tambon (sub-district) of Mueang Kanchanaburi District, in Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand. In 2017, it had a population of 16,147 people. The tambon contains 15 villages. This network of villages had its origins in northern China and this is reinforced by pottery and ceramic fragments. The pottery and ceramic fragments found at Ban Kao highlight its archaeological significance in Southeast Asia; some of these fragments are currently being kept at the Ban Kao National Museum.

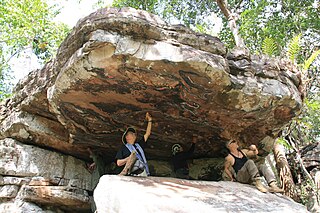

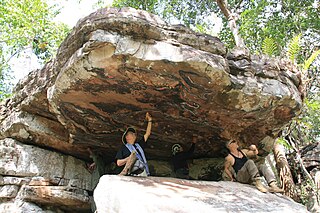

Laang Spean refers to a prehistoric cave site on top of a limestone hill in Battambang Province, north-western Cambodia. The site's name Cave of Bridges hints to the many limestone arches that remain after the partial collapse of the cave's vault. Although excavations are still in progress, at least three distinct levels of ancient human occupation are already documented. At the site's deepest layers, around 5 meters below the ground, primitive flaked stone tools were unearthed, dating back to around 71,000 years BP. Of great interest are above layers that contain records of the Hoabinhian whose stratigraphic and chronological context has yet to be defined. Future excavations at Laang Spean might help to clarify the concept and "nature of the Hoabinhian" occupation and provide new data on the Pleistocene/Holocene transition in the region

Skull Hill is an archaeological hill site located at Tampi Tampi Road, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Semporna town.

The Carcajou Point site is located in Jefferson County, Wisconsin, on Lake Koshkonong. It is a multi-component site with prehistoric Upper Mississippian Oneota and Historic components.

The Pirogues de Bercy are a group of dugout canoes dating from the Neolithic period that were discovered in 1989 during construction work in the 12th arrondissement, a neighbourhood located in southeastern Paris. The excavations of 1991–1992 unearthed two lodgings from the middle Neolithic period and one from the Late Neolithic period or the early Bronze Age. The dugouts were found at the base of these lodgings, along with other Neolithic artifacts such as pottery, stone and bone tools and arrow heads.

The sites of the Memot Circular Earthworks are located mostly in discrete eastern Cambodia and border of Vietnam in spaces between lowlands and uplands through the Mekong delta. Each earthwork is a set of two circular embankments that surround an inner platform that is slightly curved. These sites have been studied systematically starting in the 1960s. Each site is unique to the archeological artifacts found there, and studies show that these sites were inhabited over thousands of years. The current landscape of the region may contribute to the underrepresentation of these earthworks in the field of archeology, as the majority of these sites are located in modern rubber tree plantations. Many of the Neolithic period and other prehistoric sites have yet to be studied, however, as political unrest in Cambodia has contributed to inconsistencies in archeological fieldwork.

Nyaung-gan is a Bronze Age cemetery in central Myanmar, and was the first site in Myanmar to have artefacts dating to the Bronze Age. Burials found over two seasons (1998–1999) were found to have grave goods consisting of pottery filled with animal bones, beads, spear points, terracotta and jewelry, no iron was found at the site and that provides a good benchmark to start with dating of the site. The site was initially thought to be a significant site due to surface findings, so a team was assembled to investigate the validity of that claim. Myanmar is centrally located along trade routes that connect South, East, and Southeast Asia, and has great potential to show cultural influence from all stops along those trade routes. Another unique aspect of the site is that the skeletons found in the burials were left in situ, and a museum was constructed around them.