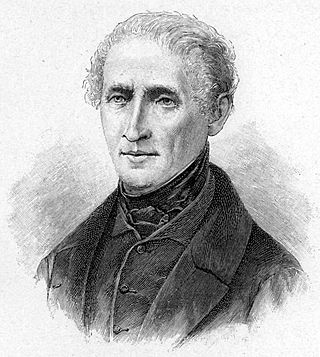

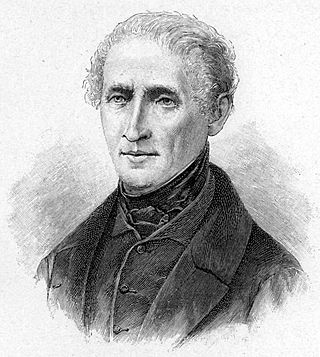

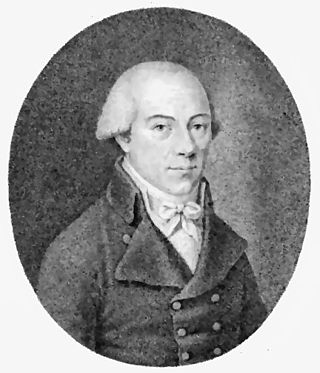

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist. His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann's Kreisleriana is based on Hoffmann's character Johannes Kreisler.

German literature comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a lesser extent works of the German diaspora. German literature of the modern period is mostly in Standard German, but there are some currents of literature influenced to a greater or lesser degree by dialects.

Romantic music is a stylistic movement in Western Classical music associated with the period of the 19th century commonly referred to as the Romantic era. It is closely related to the broader concept of Romanticism—the intellectual, artistic, and literary movement that became prominent in Western culture from about 1798 until 1837.

Romanticism was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjectivity, imagination, and appreciation of nature in society and culture during the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

German Romanticism was the dominant intellectual movement of German-speaking countries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influencing philosophy, aesthetics, literature, and criticism. Compared to English Romanticism, the German variety developed relatively early, and, in the opening years, coincided with Weimar Classicism (1772–1805).

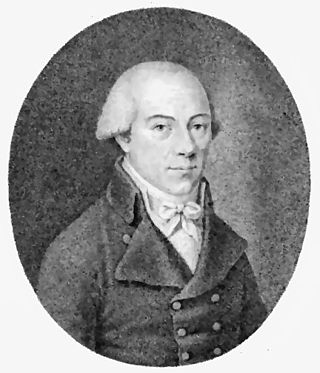

Karl Wilhelm FriedrichSchlegel was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Romanticism.

Henrik Steffens, was a Norwegian philosopher, scientist, and poet.

Das Lied von der Erde is an orchestral song cycle for two voices and orchestra written by Gustav Mahler between 1908 and 1909. Described as a symphony when published, it comprises six songs for two singers who alternate movements. Mahler specified that the two singers should be a tenor and an alto, or else a tenor and a baritone if an alto is not available.

Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff was a German poet, novelist, playwright, literary critic, translator, and anthologist. Eichendorff was one of the major writers and critics of Romanticism. Ever since their publication and up to the present day, some of his works have been very popular in German-speaking Europe.

In Western classical music, neoromanticism is a return to the emotional expression associated with nineteenth-century Romanticism. Throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, numerous composers have created works which rejected or ignored emerging styles such as Modernism and Postmodernism.

The Symphony in D minor is the best-known orchestral work and the only mature symphony written by the 19th-century composer César Franck. It employs a cyclic form, with important themes recurring in all three movements.

Ida Marie Lipsius, alias La Mara, was a German writer and music historian.

Justinus or Justin Heinrich Knecht was a German composer, organist, and music theorist.

Kurt Georg Hugo Thomas was a German composer, conductor and music educator.

Günter de Bruyn was a German author.

Hermann Ritter was a German viola player, composer and music historian.

Elsa Asenijeff, was an Austrian writer and partner of Max Klinger.

Kurt Mueller-Vollmer, born in Hamburg, Germany, was an American philosopher and professor of German Studies and Humanities at Stanford University. Mueller-Vollmer studied in Germany, France, Spain and the United States. He held a master's degree in American Studies from Brown University, and a doctorate in German Studies and Humanities from Stanford University, where he taught for over 40 years. His major publications concentrate in the areas of Literary Criticism, Hermeneutics, Phenomenology, Romantic and Comparative Literature, language theory, cultural transfer and translation studies. Mueller-Vollmer made noteworthy scholarly contributions elucidating the theoretical and empirical linguistic work of Wilhelm von Humboldt, including the discovery of numerous manuscripts previously thought lost or otherwise unknown containing Humboldt's empirical studies of numerous languages from around the world.

Starting from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, socialist writers have discussed romanticism and its relationship to the political economy.

Bernhard Ruchti is a Swiss pianist, organist, composer and music researcher.