The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family, and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no known components or substructure. The electron's mass is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton. Quantum mechanical properties of the electron include an intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of a half-integer value, expressed in units of the reduced Planck constant, ħ. Being fermions, no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state, per the Pauli exclusion principle. Like all elementary particles, electrons exhibit properties of both particles and waves: They can collide with other particles and can be diffracted like light. The wave properties of electrons are easier to observe with experiments than those of other particles like neutrons and protons because electrons have a lower mass and hence a longer de Broglie wavelength for a given energy.

The positron or antielectron is the particle with an electric charge of +1e, a spin of 1/2, and the same mass as an electron. It is the antiparticle of the electron. When a positron collides with an electron, annihilation occurs. If this collision occurs at low energies, it results in the production of two or more photons.

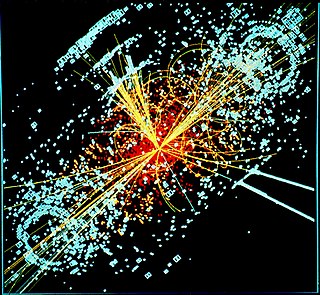

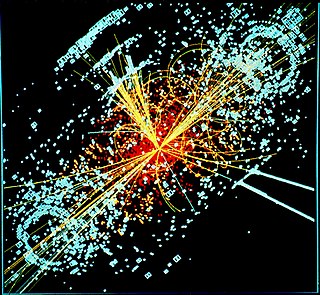

In particle physics, quantum electrodynamics (QED) is the relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics. In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quantum mechanics and special relativity is achieved. QED mathematically describes all phenomena involving electrically charged particles interacting by means of exchange of photons and represents the quantum counterpart of classical electromagnetism giving a complete account of matter and light interaction.

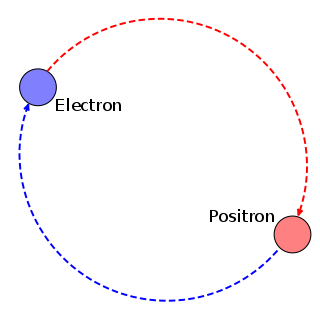

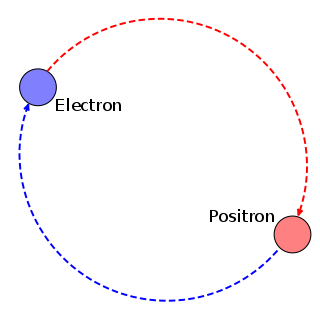

Positronium (Ps) is a system consisting of an electron and its anti-particle, a positron, bound together into an exotic atom, specifically an onium. Unlike hydrogen, the system has no protons. The system is unstable: the two particles annihilate each other to predominantly produce two or three gamma-rays, depending on the relative spin states. The energy levels of the two particles are similar to that of the hydrogen atom. However, because of the reduced mass, the frequencies of the spectral lines are less than half of those for the corresponding hydrogen lines.

Ionization is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule is called an ion. Ionization can result from the loss of an electron after collisions with subatomic particles, collisions with other atoms, molecules and ions, or through the interaction with electromagnetic radiation. Heterolytic bond cleavage and heterolytic substitution reactions can result in the formation of ion pairs. Ionization can occur through radioactive decay by the internal conversion process, in which an excited nucleus transfers its energy to one of the inner-shell electrons causing it to be ejected.

Julian Seymour Schwinger was a Nobel Prize-winning American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work on quantum electrodynamics (QED), in particular for developing a relativistically invariant perturbation theory, and for renormalizing QED to one loop order. Schwinger was a physics professor at several universities.

The Aharonov–Bohm effect, sometimes called the Ehrenberg–Siday–Aharonov–Bohm effect, is a quantum-mechanical phenomenon in which an electrically charged particle is affected by an electromagnetic potential, despite being confined to a region in which both the magnetic field and electric field are zero. The underlying mechanism is the coupling of the electromagnetic potential with the complex phase of a charged particle's wave function, and the Aharonov–Bohm effect is accordingly illustrated by interference experiments.

In quantum field theory, the quantum vacuum state is the quantum state with the lowest possible energy. Generally, it contains no physical particles. The term zero-point field is sometimes used as a synonym for the vacuum state of a quantized field which is completely individual.

In mathematics and physics, a non-perturbative function or process is one that cannot be described by perturbation theory. An example is the function

In quantum field theory, and specifically quantum electrodynamics, vacuum polarization describes a process in which a background electromagnetic field produces virtual electron–positron pairs that change the distribution of charges and currents that generated the original electromagnetic field. It is also sometimes referred to as the self-energy of the gauge boson (photon).

In quantum electrodynamics, the anomalous magnetic moment of a particle is a contribution of effects of quantum mechanics, expressed by Feynman diagrams with loops, to the magnetic moment of that particle. The magnetic moment, also called magnetic dipole moment, is a measure of the strength of a magnetic source.

In physics, the Euler–Heisenberg Lagrangian describes the non-linear dynamics of electromagnetic fields in vacuum. It was first obtained by Werner Heisenberg and Hans Heinrich Euler in 1936. By treating the vacuum as a medium, it predicts rates of quantum electrodynamics (QED) light interaction processes.

In quantum electrodynamics (QED), the Schwinger limit is a scale above which the electromagnetic field is expected to become nonlinear. The limit was first derived in one of QED's earliest theoretical successes by Fritz Sauter in 1931 and discussed further by Werner Heisenberg and his student Hans Heinrich Euler. The limit, however, is commonly named in the literature for Julian Schwinger, who derived the leading nonlinear corrections to the fields and calculated the rate of electron–positron pair production in a strong electric field. The limit is typically reported as a maximum electric field or magnetic field before nonlinearity for the vacuum of

In physics a non-neutral plasma is a plasma whose net charge creates an electric field large enough to play an important or even dominant role in the plasma dynamics. The simplest non-neutral plasmas are plasmas consisting of a single charge species. Examples of single species non-neutral plasmas that have been created in laboratory experiments are plasmas consisting entirely of electrons, pure ion plasmas, positron plasmas, and antiproton plasmas.

The Breit–Wheeler process or Breit–Wheeler pair production is a proposed physical process in which a positron–electron pair is created from the collision of two photons. It is the simplest mechanism by which pure light can be potentially transformed into matter. The process can take the form γ γ′ → e+ e− where γ and γ′ are two light quanta.

In theoretical physics, the dual photon is a hypothetical elementary particle that is a dual of the photon under electric–magnetic duality which is predicted by some theoretical models, including M-theory.

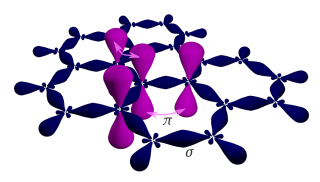

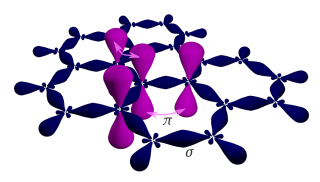

Graphene is a semimetal whose conduction and valence bands meet at the Dirac points, which are six locations in momentum space, the vertices of its hexagonal Brillouin zone, divided into two non-equivalent sets of three points. The two sets are labeled K and K'. The sets give graphene a valley degeneracy of gv = 2. By contrast, for traditional semiconductors the primary point of interest is generally Γ, where momentum is zero. Four electronic properties separate it from other condensed matter systems.

The rotating wall technique is a method used to compress a single-component plasma confined in an electromagnetic trap. It is one of many scientific and technological applications that rely on storing charged particles in vacuum. This technique has found extensive use in improving the quality of these traps and in tailoring of both positron and antiproton plasmas for a variety of end uses.

The Penning–Malmberg trap, named after Frans Penning and John Malmberg, is an electromagnetic device used to confine large numbers of charged particles of a single sign of charge. Much interest in Penning–Malmberg (PM) traps arises from the fact that if the density of particles is large and the temperature is low, the gas will become a single-component plasma. While confinement of electrically neutral plasmas is generally difficult, single-species plasmas can be confined for long times in PM traps. They are the method of choice to study a variety of plasma phenomena. They are also widely used to confine antiparticles such as positrons and antiprotons for use in studies of the properties of antimatter and interactions of antiparticles with matter.

Non-linear inverse Compton scattering (NICS), also known as non-linear Compton scattering and multiphoton Compton scattering, is the scattering of multiple low-energy photons, given by an intense electromagnetic field, in a high-energy photon during the interaction with a charged particle, in many cases an electron. This process is an inverted variant of Compton scattering since, contrary to it, the charged particle transfers its energy to the outgoing high-energy photon instead of receiving energy from an incoming high-energy photon. Furthermore, differently from Compton scattering, this process is explicitly non-linear because the conditions for multiphoton absorption by the charged particle are reached in the presence of a very intense electromagnetic field, for example, the one produced by high-intensity lasers.