Ecological selection refers to natural selection without sexual selection, i.e. strictly ecological processes that operate on a species' inherited traits without reference to mating or secondary sex characteristics. The variant names describe varying circumstances where sexual selection is wholly suppressed as a mating factor.

Amplexus is a type of mating behavior exhibited by some externally fertilizing species in which a male grasps a female with his front legs as part of the mating process, and at the same time or with some time delay, he fertilizes the eggs, as they are released from the female's body. In amphibians, females may be grasped by the head, waist, or armpits, and the type of amplexus is characteristic of some taxonomic groups.

Behavioral ecology, also spelled behavioural ecology, is the study of the evolutionary basis for animal behavior due to ecological pressures. Behavioral ecology emerged from ethology after Niko Tinbergen outlined four questions to address when studying animal behaviors: What are the proximate causes, ontogeny, survival value, and phylogeny of a behavior?

Ursus is a genus in the family Ursidae (bears) that includes the widely distributed brown bear, the polar bear, the American black bear, and the Asian black bear. The name is derived from the Latin ursus, meaning bear.

Evolutionary game theory (EGT) is the application of game theory to evolving populations in biology. It defines a framework of contests, strategies, and analytics into which Darwinian competition can be modelled. It originated in 1973 with John Maynard Smith and George R. Price's formalisation of contests, analysed as strategies, and the mathematical criteria that can be used to predict the results of competing strategies.

The marginal value theorem (MVT) is an optimality model that usually describes the behavior of an optimally foraging individual in a system where resources are located in discrete patches separated by areas with no resources. Due to the resource-free space, animals must spend time traveling between patches. The MVT can also be applied to other situations in which organisms face diminishing returns.

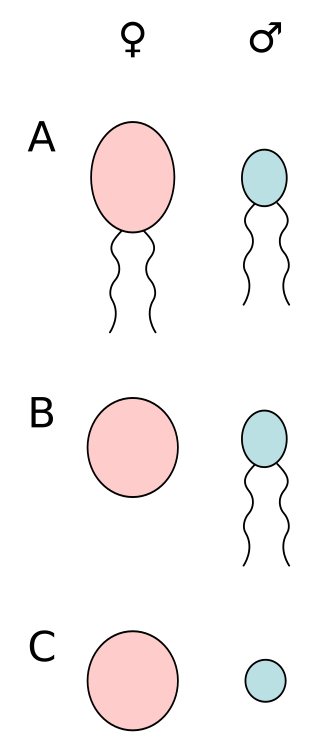

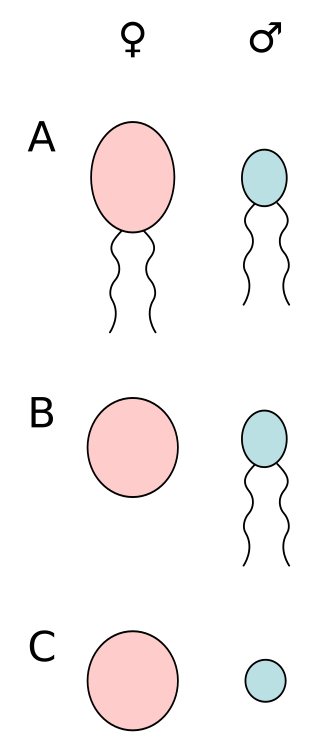

Anisogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves the union or fusion of two gametes that differ in size and/or form. The smaller gamete is male, a sperm cell, whereas the larger gamete is female, typically an egg cell. Anisogamy is predominant among multicellular organisms. In both plants and animals gamete size difference is the fundamental difference between females and males.

Intraspecific competition is an interaction in population ecology, whereby members of the same species compete for limited resources. This leads to a reduction in fitness for both individuals, but the more fit individual survives and is able to reproduce. By contrast, interspecific competition occurs when members of different species compete for a shared resource. Members of the same species have rather similar requirements for resources, whereas different species have a smaller contested resource overlap, resulting in intraspecific competition generally being a stronger force than interspecific competition.

Competition is an interaction between organisms or species in which both require a resource that is in limited supply. Competition lowers the fitness of both organisms involved since the presence of one of the organisms always reduces the amount of the resource available to the other.

Monogamous pairing in animals refers to the natural history of mating systems in which species pair bond to raise offspring. This is associated, usually implicitly, with sexual monogamy.

In ecology, an ideal free distribution (IFD) is a theoretical way in which a population's individuals distribute themselves among several patches of resources within their environment, in order to minimize resource competition and maximize fitness. The theory states that the number of individual animals that will aggregate in various patches is proportional to the amount of resources available in each. For example, if patch A contains twice as many resources as patch B, there will be twice as many individuals foraging in patch A as in patch B.

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, both in ancient and in recent times.

Interspecific competition, in ecology, is a form of competition in which individuals of different species compete for the same resources in an ecosystem. This can be contrasted with mutualism, a type of symbiosis. Competition between members of the same species is called intraspecific competition.

The red flour beetle is a species of beetle in the family Tenebrionidae, the darkling beetles. It is a worldwide pest of stored products, particularly food grains, and a model organism for ethological and food safety research.

A biological ornament is a characteristic of an animal that appears to serve a decorative function rather than a utilitarian function. Many are secondary sexual characteristics, and others appear on young birds during the period when they are dependent on being fed by their parents. Ornaments are used in displays to attract mates, which may lead to the evolutionary process known as sexual selection. An animal may shake, lengthen, or spread out its ornament in order to get the attention of the opposite sex, which will in turn choose the most attractive one with which to mate. Ornaments are most often observed in males, and choosing an extravagantly ornamented male benefits females as the genes that produce the ornament will be passed on to her offspring, increasing their own reproductive fitness. As Ronald Fisher noted, the male offspring will inherit the ornament while the female offspring will inherit the preference for said ornament, which can lead to a positive feedback loop known as a Fisherian runaway. These structures serve as cues to animal sexual behaviour, that is, they are sensory signals that affect mating responses. Therefore, ornamental traits are often selected by mate choice.

Polygyny is a mating system in which one male lives and mates with multiple females but each female only mates with a single male. Systems where several females mate with several males are defined either as promiscuity or polygynandry. Lek mating is frequently regarded as a form of polygyny, because one male mates with many females, but lek-based mating systems differ in that the male has no attachment to the females with whom he mates, and that mating females lack attachment to one another.

Sexual selection in insects is about how sexual selection functions in insects. The males of some species have evolved exaggerated adornments and mechanisms for self-defense. These traits play a role in increasing male reproductive expectations by triggering male-male competition or influencing the female mate choice, and can be thought of as functioning on three different levels: individuals, colonies, and populations within an area.

An alternative mating strategy is a strategy used by male or female animals, often with distinct phenotypes, that differs from the prevailing mating strategy of their sex. Such strategies are diverse and variable both across and within species. Animal sexual behaviour and mate choice directly affect social structure and relationships in many different mating systems, whether monogamous, polygamous, polyandrous, or polygynous. Though males and females in a given population typically employ a predominant reproductive strategy based on the overarching mating system, individuals of the same sex often use different mating strategies. Among some reptiles, frogs and fish, large males defend females, while small males may use sneaking tactics to mate without being noticed.

In ecology, contest competition refers to a situation where available resources, such as food and mates, are utilized only by one or a few individuals, thus preventing development or reproduction of other individuals. It refers to a hypothetical situation in which several individuals stage a contest for which one eventually emerges victorious. Contest competition is the opposite of scramble competition, a situation in which available resources are shared equally among individuals.

Primate sociality is an area of primatology that aims to study the interactions between three main elements of a primate social network: the social organisation, the social structure and the mating system. The intersection of these three structures describe the socially complex behaviours and relationships occurring among adult males and females of a particular species. Cohesion and stability of groups are maintained through a confluence of factors, including: kinship, willingness to cooperate, frequency of agonistic behaviour, or varying intensities of dominance structures.