The Constitution of 3 May 1791, titled the Governance Act, was a constitution adopted by the Great Sejm for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a dual monarchy comprising the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Constitution was designed to correct the Commonwealth's political flaws. It had been preceded by a period of agitation for—and gradual introduction of—reforms, beginning with the Convocation Sejm of 1764 and the ensuing election that year of Stanisław August Poniatowski, the Commonwealth's last king.

Pacta conventa was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" and a newly elected king upon his "free election" to the throne.

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles were a permanent contract between the "Polish nation" and a newly elected king upon his election to the throne. It stated the fundamental principles of governance and constitutional law in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Pospolite ruszenie is a name for the mobilisation of armed forces during the period of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The tradition of wartime mobilisation of part of the population existed from before the 13th century to the 19th century. In the later era, pospolite ruszenie units were formed from the szlachta. The pospolite ruszenie was eventually outclassed by professional forces.

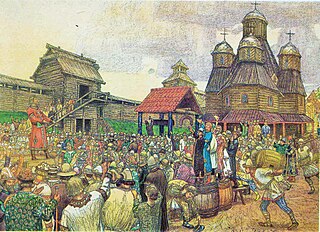

Veche was a popular assembly in medieval Slavic countries.

The liberum veto was a parliamentary device in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was a form of unanimity voting rule that allowed any member of the Sejm (legislature) to force an immediate end to the current session and to nullify any legislation that had already been passed at the session by shouting either Sisto activitatem! or Nie pozwalam!. The rule was in place from the mid-17th century to the late 18th century in the Sejm's parliamentary deliberations. It was based on the premise that since all Polish noblemen were equal, every measure that came before the Sejm had to be passed unanimously. The liberum veto was a key part of the political system of the Commonwealth, strengthening democratic elements and checking royal power and went against the European-wide trend of having a strong executive.

A rokosz originally was a gathering of all the Polish szlachta (nobility), not merely of deputies, for a sejm. The term was introduced to the Polish language from Hungary, where analogous gatherings took place at a field called Rákos. With time, "rokosz" came to signify an armed, semi-legal rebellion by the szlachta of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth against the king, in the name of defending threatened liberties. The nobles who gathered for a rokosz formed a "confederation".

A konfederacja was an ad hoc association formed by Polish–Lithuanian szlachta (nobility), clergy, cities, or military forces in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth for the attainment of stated aims. A konfederacja often took the form of an armed rebellion aimed at redressing perceived abuses or trespasses of some authority. Such "confederations" acted in lieu of state authority or to force their demands upon that authority. They could be seen as a primary expression of direct democracy and right of revolution in the Commonwealth, and as a way for the nobles to act on their grievances and against the state's central authority.

The Great Sejm, also known as the Four-Year Sejm was a Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that was held in Warsaw between 1788 and 1792. Its principal aim became to restore sovereignty to, and reform, the Commonwealth politically and economically.

A sejmik was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of Poland, though they gained significantly more influence in the later era of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Sejmiks arose around the late 14th and early 15th centuries and existed until the end of the Commonwealth in 1795, following the partitions of the Commonwealth. In a limited form, some sejmiks existed in partitioned Poland (1795–1918), and later in the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939). In modern Poland, since 1999, the term has revived with the voivodeship sejmiks, referring to the elected councils of each of the 16 voivodeships.

Royal elections in Poland were the elections of individual kings, rather than dynasties, to the Polish throne. Based on traditions dating to the very beginning of the Polish statehood, strengthened during the Piast and Jagiellon dynasties, they reached their final form in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth period between 1572 and 1791. The "free election" was abolished by the Constitution of 3 May 1791, which established a constitutional-parliamentary monarchy.

The General Sejm was the bicameral parliament of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was established by the Union of Lublin in 1569 from the merger of the Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland and the Seimas of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia. It was one of the primary elements of the democratic governance in the Commonwealth. The sejm was a powerful political institution and the king could not pass laws without the approval of that body.

The Cardinal Laws were a quasi-constitution enacted in Warsaw, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, by the Repnin Sejm of 1767–68. Enshrining most of the conservative laws responsible for the inefficient functioning of the Commonwealth, and passed under foreign duress, they have been seen rather negatively by historians.

The Constitution of 3 May 1791 is an 1891 Romantic oil painting on canvas by the Polish artist Jan Matejko. It is a large piece, and one of Matejko's best known. It memorializes the Polish Constitution of 3 May 1791, a milestone in the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and a high point of the Polish Enlightenment.

Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw was the parliament of the Duchy of Warsaw. It was created in 1807 by Napoleon, who granted a new constitution to the recently created Duchy. It had limited competences, including having no legislative initiative. It met three times: for regular sessions in 1809 and 1811, and for an extraordinary session in 1812. In the history of Polish parliament, it succeeded the Sejm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and was followed by the Sejm of the Congress Poland.

The Sejm of Congress Poland was the parliament in the 19th century Kingdom of Poland, colloquially known as Congress Poland. It existed from 1815 to 1831. In the history of the Polish parliament, it succeeded the Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw.

Serfdom in Poland became the dominant form of relationship between peasants and nobility in the 17th century, and was a major feature of the economy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, although its origins can be traced back to the 12th century.

The privileges of the szlachta formed a cornerstone of "Golden Liberty" in the Kingdom of Poland and, later, in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569-1795). Most szlachta privileges were obtained between the late-14th and early-16th centuries. By the end of that period, the szlachta had succeeded in garnering numerous rights, empowering themselves and limiting the powers of the elective Polish monarchy to an extent unprecedented elsewhere in Europe at the time.

The Sejm of the Grand Duchy of Posen was the parliament in the 19th century Grand Duchy of Posen and the Province of Posen, seated in Poznań/Posen. It existed from 1823 to 1918. In the history of the Polish parliament, it succeeded the general sejm and local sejmik on part of the territories of the Prussian partition. Originally retaining a Polish character, it acquired a more German character in the second half of the 19th century.

The Sejm of the Estates or Estates of Galicia were the parliament in the first half of the 19th century Galicia region in Austrian Empire. The body existed from 1775 to 1845. In the history of the Polish parliament, it succeeded the general sejm and local sejmiks on the territories of the Austrian partition. The Estates were disbanded following the Kraków Uprising of 1846. In 1861 they were succeeded by the Sejm of the Land.