The Kingdom of the South Saxons, today referred to as the Kingdom of Sussex, was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the Heptarchy of Anglo-Saxon England. On the south coast of the island of Great Britain, it was originally a sixth-century Saxon colony and later an independent kingdom. The kingdom remains one of the least known of the Anglo-Saxon polities, with no surviving king-list, several local rulers and less centralisation than other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The South Saxons were ruled by the kings of Sussex until the country was annexed by Wessex, probably in 827, in the aftermath of the Battle of Ellendun. In 860 Sussex was ruled by the kings of Wessex, and by 927 all remaining Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were ruled by them as part of the new kingdom of England.

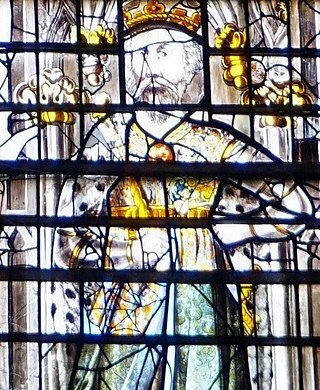

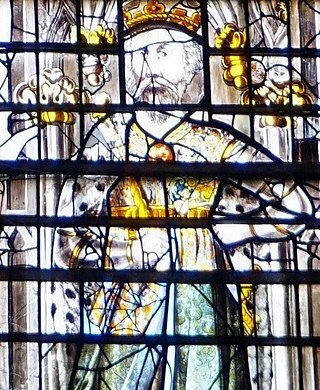

Wilfrid was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and became the abbot of a newly founded monastery at Ripon. In 664 Wilfrid acted as spokesman for the Roman position at the Synod of Whitby, and became famous for his speech advocating that the Roman method for calculating the date of Easter should be adopted. His success prompted the king's son, Alhfrith, to appoint him Bishop of Northumbria. Wilfrid chose to be consecrated in Gaul because of the lack of what he considered to be validly consecrated bishops in England at that time. During Wilfrid's absence Alhfrith seems to have led an unsuccessful revolt against his father, Oswiu, leaving a question mark over Wilfrid's appointment as bishop. Before Wilfrid's return Oswiu had appointed Ceadda in his place, resulting in Wilfrid's retirement to Ripon for a few years following his arrival back in Northumbria.

Æthelred was king of Mercia from 675 until 704. He was the son of Penda of Mercia and came to the throne in 675, when his brother, Wulfhere of Mercia, died from an illness. Within a year of his accession he invaded Kent, where his armies destroyed the city of Rochester. In 679 he defeated his brother-in-law, Ecgfrith of Northumbria, at the Battle of the Trent: the battle was a major setback for the Northumbrians, and effectively ended their military involvement in English affairs south of the Humber. It also permanently returned the Kingdom of Lindsey to Mercia's possession. However, Æthelred was unable to re-establish his predecessors' domination of southern Britain.

Ine or Ini was King of Wessex from 689 to 726. At Ine's accession, his kingdom dominated much of what is now southern England. However, he was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla of Wessex, who had expanded West Saxon territory substantially. By the end of Ine's reign, the kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, and Essex were no longer under West Saxon sway; however, Ine maintained control of what is now Hampshire, and consolidated and extended Wessex's territory in the western peninsula.

Cædwalla was the King of Wessex from approximately 685 until he abdicated in 688. His name is derived from the Welsh Cadwallon. He was exiled from Wessex as a youth and during this period gathered forces and attacked the South Saxons, killing their king, Æthelwealh, in what is now Sussex. Cædwalla was unable to hold the South Saxon territory, however, and was driven out by Æthelwealh's ealdormen. In either 685 or 686, he became King of Wessex. He may have been involved in suppressing rival dynasties at this time, as an early source records that Wessex was ruled by underkings until Cædwalla.

Selsey is a seaside town and civil parish, about eight miles (12 km) south of Chichester, in the Chichester district, in West Sussex, England. Selsey lies at the southernmost point of the Manhood Peninsula, almost cut off from mainland Sussex by the sea. It is bounded to the west by Bracklesham Bay, to the north by Broad Rife, to the east by Pagham Harbour and terminates in the south at Selsey Bill. There are significant rock formations beneath the sea off both of its coasts, named the Owers rocks and Mixon rocks. Coastal erosion has been an ever-present problem for Selsey. In 2011 the parish had a population of 10,737.

Berhtwald was the ninth Archbishop of Canterbury in England. His predecessor had been Theodore of Tarsus. Berhtwald begins the first continuous series of native-born Archbishops of Canterbury, although there had been previous Anglo-Saxon archbishops, they did not succeed each other until Berhtwald's successor Tatwine.

Æthelwealh was ruler of the ancient South Saxon kingdom from before 674 till his death between 680 and 685. According to the Venerable Bede, Æthelwealh was baptised in Mercia, becoming the first Christian king of Sussex. He was killed by a West Saxon prince, Cædwalla, who eventually became king of Wessex.

Eadberht of Selsey was an abbot of Selsey Abbey, later promoted to become the first Bishop of Selsey. He was consecrated sometime between 709 and 716, and died between 716 and 731. Wilfrid has occasionally been regarded as a previous bishop of the South Saxons, but this is an insertion of his name into the episcopal lists by later medieval writers, and Wilfrid was not considered the bishop during his lifetime or Bede's.

Brihthelm or Beorhthelm was a Bishop of Selsey.

Stigand was the last Bishop of Selsey, and first Bishop of Chichester.

Bosa was an Anglo-Saxon Bishop of York during the 7th and early 8th centuries. He was educated at Whitby Abbey, where he became a monk. Following Wilfrid's removal from York in 678 the diocese was divided into three, leaving a greatly reduced see of York, to which Bosa was appointed bishop. He was himself removed in 687 and replaced by Wilfrid, but in 691 Wilfrid was once more ejected and Bosa returned to the see. He died in about 705, and subsequently appears as a saint in an 8th-century liturgical calendar.

Selsey Bill is a headland into the English Channel on the south coast of England in the county of West Sussex.

The Bishop of Chichester is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers the counties of East and West Sussex. The see is based in the City of Chichester where the bishop's seat is located at the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity. On 3 May 2012 the appointment was announced of Martin Warner, Bishop of Whitby, as the next Bishop of Chichester. His enthronement took place on 25 November 2012 in Chichester Cathedral.

The Haestingas, Heastingas or Hæstingas were one of the tribes of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Not very much is known about them. They settled in what became East Sussex sometime before the end of the 8th century. A 12th-century source suggested that they were conquered by Offa of Mercia, in 771. They were also recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC) as being an autonomous grouping as late as the 11th century.

Arwald was the last heathen Anglo-Saxon king and the last king of the Wihtwara, a people group that inhabited the Isle of Wight. He was killed by Cædwalla of Wessex during an invasion of his kingdom, at which point the island was Christianised. During the invasion, his two brothers were baptised before also being killed and are now venerated as saints.

Cymenshore was a place in Southern England where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ælle of Sussex landed in AD 477 and battled the Britons with his three sons Cymen, Wlencing and Cissa, after the first of whom Cymenshore was held to have been named. The spelling Cymenshore is a scholarly modernisation of the Old English Cȳmenes ōra, which is now lost. Its location is unclear but was probably near Selsey.

St Peter's Church is the parish church of Selsey, West Sussex, and dates from the 13th century. The church building was originally situated at the location of St Wilfrid's first monastery and cathedral at Church Norton some 2 miles north of the present centre of population. The church is a Grade II listed building, and there has been extensive renovation work on and inside the building.

The Manhood Peninsula is in the southwest of West Sussex in England. It has the English Channel to its south and Chichester to the north. It is bordered to its west by Chichester Harbour and to its east by Pagham Harbour, its southern headland being Selsey Bill.

St Wilfrid's Chapel, also known as St Wilfrid's Church and originally as St Peter's Church, is a former Anglican church at Church Norton, a rural location near the village of Selsey in West Sussex, England. In its original, larger form, the church served as Selsey's parish church from the 13th century until the mid 1860s; when half of it was dismantled, moved to the centre of the village and rebuilt along with modern additions. Only the chancel of the old church survived in its harbourside location of "sequestered leafiness", resembling a cemetery chapel in the middle of its graveyard. It was rededicated to St Wilfrid—7th-century founder of a now vanished cathedral at Selsey—and served as a chapel of ease until the Diocese of Chichester declared it redundant in 1990. Since then it has been in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust charity. The tiny chapel, which may occupy the site of an ancient monastery built by St Wilfrid, is protected as a Grade I Listed building.