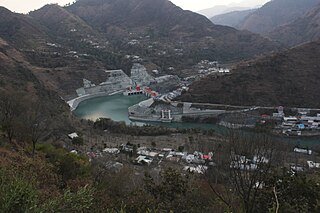

The Shuakhevi Hydro Power Plant (Skuakhevi HPP) is a run-of-the-river plant in Adjara, Georgia. 41°39′27″N42°20′59″E / 41.6576°N 42.3497°E Construction on the project began in 2013 and was completed in April 2021. [1] It has an installed capacity of 185 megawatts (248,000 hp) with expected electricity output of 452 gigawatt-hours (1,630 TJ). The plant has the capacity for diurnal storage in two reservoirs [2] (22-metre (72 ft) Skhalta dam with a 19.4-hectare (48-acre) reservoir and 39-metre (128 ft) Didachara dam with a 16.9-hectare (42-acre) reservoir), [3] allowing Shuakhevi HPP to store water for up to 12 hours and sell electricity at peak demand times. [2] Three main tunnels were constructed on the Shuakhevi project; the 5.8 km Chirukhistsqali to Skhalta transfer tunnel, the 9.1 kilometres (5.7 mi) Skhalta to Didachara transfer tunnel and the 17.8 km Shuakhevi headrace and pressure tunnel. [4] It is estimated that the project will cost US$417 million. For the purposes of developing, constructing and operating the Shuakhevi HPP, ADB and EBRD extended a loan to Adjaristsqali Georgia LLC of up to $86.5 million and IFC a loan of 80m USD. [2] Adjaristsqali Georgia LLC is owned by the Norwegian Clean Energy Invest AS (40%), India's Tata Power (40%) and IFC Infraventures (20%), an investment fund created by the International Finance Corporation. [3] Alstom was chosen to supply the electromechanical equipment for the project. [5]

Electricity demand in Georgia has been on the rise since 2009 and investment in new generation capacity is lagging behind. [6] Georgia has about 40 billion kwt/h of potential electricity and only 18-20% is utilized today. [7] The Shuakhevi HPP is a part of a large Georgian strategy to develop its hydropower potential. It will enable Georgia to use more of its energy resources to meet electricity demand during the winter months of December, January and February. [4] Most of the energy will be exported to Turkey. [8] The positive aspects of the investment according to EBRD include strengthening Georgia’s private energy sector, demonstrating new financing methods (the project will be the first power project in Georgia to rely on limited recourse financing) and setting standards for corporate governance and business conduct. [2] It will also generate employment opportunities for local population. More than 700 Georgians were working in the project in 2016, most of them from the local communities. [2] Almost 500 locals were trained in a school especially designed to build required technical skills. [8] The project company has also funded an extensive CSR program in the valley with significant infrastructure upgrades for the local communities, support for local businesses etc. [3] The project has also enabled the construction of a new 220 kV transmission line from Akhalsikhe to Batumi, significantly strengthening the grid connection in the whole of South Western Georgia. [4]

The contract for the Shuakhevi HPP project is the only contract for a hydropower project in Georgia where articles related to obligations of the state and the company on electricity tariffs and economic profitability are kept confidential. It is hard to say how the project will benefit Georgia, since it is not clear how the money will end up in the state budget. [3]

The project has responsibility to deliver electricity for three winter months in Georgia for a fixed tariff, contributing to reducing the need to import electricity and reducing the carbon emissions from electricity production in Georgia. [5]

The project will pay 1% of invested amount in property taxes to the local municipality where the infrastructure is located, which is estimated to significantly increase the budgets in the municipalities hosting the infrastructure. [6]

The project is designed to divert water flows from the upper parts of the Adjaristskali, Skhalta and Chirukhistskali rivers towards the reservoirs and then the powerhouse and leave only 10 percent of the average annual flow of the rivers. That will have a negative impact on the river ecosystem, including red-listed species like trout. [3]

Since there are no villages within the project site, the project did not envisage resettlement of local population. However, the project site is characterised by landslides. The tunnel drilled under the village Ghurta, which is one of three diversion tunnels part of the project, did not trigger any landslide as feared by the local population. Detailed geological investigations were undertaken by Mott MacDonald, one of the leading underground geological engineers in the world before the construction started to ensure that it was safe to construct a dam in the Didachara area. [8] The memory of the 1971 landslide which cost 22 people’s lives is still very much alive among local population. Adjaristsqali Georgia LLC is denying the risks, however they are reluctant to sign warranty contracts to offer compensation in case the constructions cause damages. [9]

On 8 March there was a protest against the Shuakhevi HPP. About 500 villagers blocked the road to prevent the construction of a tunnel for the 187 MW Shuakhevi HPP in Didachara were dispersed by policemen and special forces. The main concern of the people is that the construction would trigger landslides. [9]

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower. Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and also more than nuclear power. Hydropower can provide large amounts of low-carbon electricity on demand, making it a key element for creating secure and clean electricity supply systems. A hydroelectric power station that has a dam and reservoir is a flexible source, since the amount of electricity produced can be increased or decreased in seconds or minutes in response to varying electricity demand. Once a hydroelectric complex is constructed, it produces no direct waste, and almost always emits considerably less greenhouse gas than fossil fuel-powered energy plants. However, when constructed in lowland rainforest areas, where part of the forest is inundated, substantial amounts of greenhouse gases may be emitted.

Dams and reservoirs in Laos are the cornerstone of the Lao government's goal of becoming the "battery of Asia".

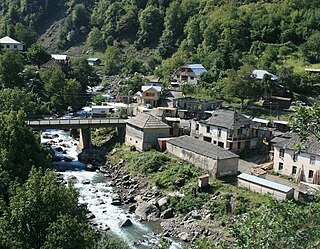

Shuakhevi is a small town in Georgia's Autonomous Republic of Adjara, 67 km east to the regional capital Batumi. Situated on the right bank of the Adjaristsqali River, it is an administrative center of Shuakhevi District, which comprises the town itself and 67 adjoining mountainous villages. The area of the district is 588 km2; population – 15,044 (2014).

The Enguri Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the Enguri River in Tsalenjikha, Georgia. Currently, it is the world's second highest concrete arch dam, with a height of 271.5 metres (891 ft). It is located north of the town of Jvari. It is part of the Enguri hydroelectric power station (HES) which is partially located in Abkhazia.

The Capanda Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the Kwanza River in Malanje Province, Angola. Built in 1987–2007 by the Russian company Tekhnopromexport, general designer - the institute Hydroproject The facility generates power by utilizing four turbines and 130 megawatts (170,000 hp) each, totalling the installed capacity to 520 megawatts (700,000 hp). Total cost of US$4 billion. An additional cost of more than US$400 million was spent in repairing the damage caused during UNITA's occupation of the area at the time of the Angolan Civil War in 1992 and 1999.

The Buk Bijela Hydro Power Plant is proposed hydroelectric power plant (HPP) on the Drina River in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Boškov Most Hydro Power Plant, referred to as Boškov Most HPP, is a derivation plant planned to be built in Mala Reka valley, in the southernmost part of the Mavrovo National Park, in North Macedonia. It will have a total capacity of 71,5 MW. Construction is expected to last 4 years.

Khudoni Hydro Power Plant, hereinafter referred to as Khudoni HPP, is a projected power plant on Enguri River, in Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti, Georgia that has 3 turbines with a nominal capacity of 233.3 MW each having a total capacity of 700 MW. The power plant is associated with a planned 200.5-metre (658 ft) tall concrete double-arch-gravity dam. According to the Georgian government-commissioned and the World Bank-supported study the construction of Namakhvani, Paravani and Khudoni hydro power plants are the most attractive scenarios for the development of Georgia's energy sector.

Irganai Dam is a hydroelectric dam in the Untskul region of Dagestan, Russia. It is located on the river Avar Koisu.

The Dniester Pumped Storage Power Station is a pumped storage hydroelectric scheme that uses the Dniester River 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) northeast of Sokyriany in Chernivtsi Oblast, Ukraine. Currently, four of seven 324-megawatt (434,000 hp) generators are operational and when complete in 2028, the power station will have an installed capacity of 2,268 megawatts (3,041,000 hp).

In 2021, hydroelectricity generated 11% of Bulgaria’s electricity. As of 2020, the country's total installed electricity capacity was approximately 12,839 MW, with hydropower contributing 25%, or 3,213 MW.

Patrind Hydropower Plant is a run-of-the-river, high head project of 110 metres (360 ft), located on Kunhar River near Patrind Village of Mansehra District, right on the border of Abbottabad District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province and Muzaffarabad city of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. It is approximately 138 kilometres (86 mi) from Rawalpindi and Islamabad and about 76 kilometres (47 mi) from Abbottabad city.

Dariali Hydropower Plant, referred to as Dariali HPP, is a 108 MW run-of-the-river hydropower plant built in 2017 in Georgia. It is located on the Tergi River in Kazbegi Municipality, at less than 1 km from the Russian-Georgian border, 160 km far from Tbilisi.

Sevan–Hrazdan Cascade is a complex of hydroelectric power plants on the Hrazdan River and its tributaries between the Lake Sevan and Yerevan in Armenia. They use irrigation water flow from the Lake Sevan and streams waters of Hrazdan River. The cascade is owned by the International Energy Corporation (IEC), a subsidiary of Tashir Group owned by Samvel Karapetyan.

The Vorotan Cascade, or the ContourGlobal Hydro Cascade, is a cascade on the Vorotan River in Syunik Province, Armenia. It was built to produce hydroelectric power and provide irrigation water. The Vorotan Cascade consists of three hydroelectric power plants and five reservoirs with a combined installed capacity of 404.2 MW. It is one of the main power generation complexes in Armenia.

Nenskra Hydro Power Plant is a proposed hydroelectric power station to be located on the southern slopes of the Central Caucasus mountains in Svaneti, Georgia.

CEE Bankwatch Network is a global network which operates in central and eastern Europe. There are 17 member groups, multiple non-governmental organizations based in different locations; the network is one of the largest networks of environmental NGOs in central and eastern Europe. Bankwatch's headquarters rest in Prague, Czech Republic.

The power generation potential of the rivers in Azerbaijan is estimated at 40 billion kilowatt per hour, and feasible potential is 16 billion kilowatt per hour. Small-scale hydro has significant developmental potential in Azerbaijan. In particular, the lower reaches of the Kura river, the Aras river and other rivers flowing into the Caspian Sea. Hydropower could conceivably provide up to 30% of Azerbaijan’s electricity requirements. Currently, hydropower, dominated by large-scale dams, provides 11.4% of Azerbaijan’s electricity.

Hydropower generates about 30% of Armenia's electricity but its share varies a lot from year to year.

The Mavrovo Hydropower System is a collection of three hydroelectric power plants in North Macedonia. It plays a crucial role in electricity generation within the region. The system includes Vrutok HPP, Rаven HPP, and Vrben HPP. The largest capacity is in the hydropower plant "Vrutok" with four generators. Several kilometers downstream towards Gostivar is the second power plant, "Raven," with three generators. The final power plant in the system is located in the village of Vrben and operates with two generators.