Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian classical music. Early influences of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and other Russian composers gave way to a thoroughly personal idiom notable for its song-like melodicism, expressiveness and rich orchestral colours. The piano is featured prominently in Rachmaninoff's compositional output and he made a point of using his skills as a performer to fully explore the expressive and technical possibilities of the instrument.

The Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43, is a concertante work written by Sergei Rachmaninoff for piano and orchestra, closely resembling a piano concerto, all in a single movement. Rachmaninoff wrote the work at his summer home, the Villa Senar in Switzerland, according to the score, from 3 July to 18 August 1934. Rachmaninoff himself, a noted performer of his own works, played the piano part at the piece's premiere on 7 November 1934, at the Lyric Opera House in Baltimore, Maryland, with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski.

Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53, known as the Waldstein, is one of the three most notable sonatas of his middle period. Completed in summer 1804 and surpassing Beethoven's previous piano sonatas in its scope, the Waldstein is a key early work of Beethoven's "Heroic" decade (1803–1812) and set a standard for piano composition in the grand manner.

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18, is a concerto for piano and orchestra composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff between June 1900 and April 1901. From the summer to the autumn of 1900, he worked on the second and third movements of the concerto, with the first movement causing him difficulties. Both movements of the unfinished concerto were first performed with him as soloist and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] 1900. The first movement was finished in 1901 and the complete work had an astoundingly successful premiere on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1901, again with the composer as soloist and Siloti conducting. Gutheil published the work the same year. The piece established Rachmaninoff's fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.

Étude Op. 10, No. 12 in C minor, known as the "Revolutionary Étude" or the "Étude on the Bombardment of Warsaw", is a solo piano work by Frédéric Chopin written c. 1831, and the last in his first set, Etudes, Op. 10, dedicated "à son ami Franz Liszt".

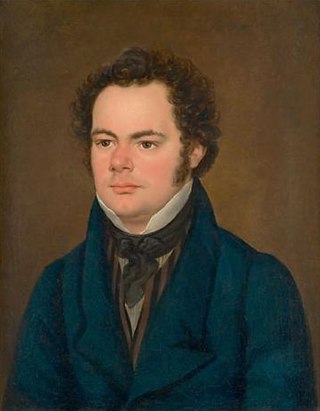

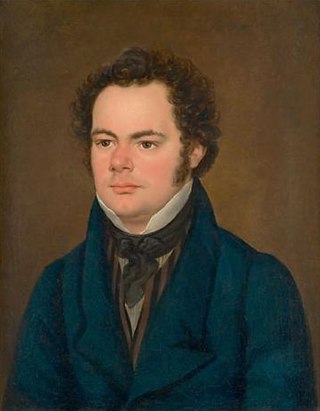

Franz Schubert's Impromptus are a series of eight pieces for solo piano composed in 1827. They were published in two sets of four impromptus each: the first two pieces in the first set were published in the composer's lifetime as Op. 90; the second set was published posthumously as Op. 142 in 1839. The third and fourth pieces in the first set were published in 1857. The two sets are now catalogued as D. 899 and D. 935 respectively. They are considered to be among the most important examples of this popular early 19th-century genre.

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 by Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff was written from October 1906 to April 1907. The premiere was performed at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg on 26 January 1908, with the composer conducting. Its duration is approximately 60 minutes when performed uncut; cut performances can be as short as 35 minutes. The score is dedicated to Sergei Taneyev, a Russian composer, teacher, theorist, author, and pupil of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The piece remains one of the composer's most popular and best known compositions.

Sergei Prokofiev set to work on his Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16, in 1912 and completed it the next year. But that version of the concerto is lost; the score was destroyed in a fire following the Russian Revolution. Prokofiev reconstructed the work in 1923, two years after finishing his Piano Concerto No. 3, and declared it to be "so completely rewritten that it might almost be considered [Piano Concerto] No. 4." Indeed its orchestration has features that clearly postdate the 1921 concerto. Performing as soloist, Prokofiev premiered this "No. 2" in Paris on 8 May 1924 with Serge Koussevitzky conducting. It is dedicated to the memory of Maximilian Schmidthof, a friend of Prokofiev's at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory who had killed himself in 1913.

The Études-Tableaux, Op. 39 is the second set of piano études composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Étude Op. 25, No. 11 in A minor, often referred to as Winter Wind in English, is a solo piano technical study composed by Frédéric Chopin in 1836. It was first published together with all études of Opus 25 in 1837, in France, Germany, and England. The first French edition indicates a common time time signature, but the manuscript and the first German edition both feature cut time. The first four bars that characterize the melody were added just before publication at the advice of Charles A. Hoffmann, a friend. Winter Wind is considered one of the most difficult of Chopin's 24 études.

Étude Op. 10, No. 8 in F major is a technical study composed by Frédéric Chopin. This work follows on from No. 7 as being primarily another work concerned with counterpoint. In this case, however, the principal melody is in the left hand, the secondary being embedded in the arpeggios of the right hand. As with many of the études, the work is divided into three sections – bars 1–28, 29–60 and 61–95.

Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 36, is a piano sonata in B-flat minor composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1913, who revised it in 1931, with the note, "The new version, revised and reduced by author."

The Nocturnes, Op. 27 are a set of two nocturnes for solo piano composed by Frédéric Chopin. The pieces were composed in 1836 and published in 1837. Both nocturnes in this opus are dedicated to Countess d'Appony.

The composer Sergei Rachmaninoff produced a number of solo piano pieces that were either lost, unpublished, or not assigned an opus number. While often disregarded in the concert repertoire, they are nevertheless part of his oeuvre. Sixteen of these pieces are extant; all others are lost. Ten of these pieces were composed before he completed his Piano Concerto No. 1, his first opus, and the rest interspersed throughout his later life. In these casual works, he draws upon the influence of other composers, including Frédéric Chopin and Pyotr Tchaikovsky. The more substantial works, the Three Nocturnes and Four Pieces, are sets of well-thought out pieces that are his first attempts at cohesive structure among multiple pieces. Oriental Sketch and Prelude in D minor, two pieces he composed very late in his life, are short works that exemplify his style as a mature composer. Whether completed as a child or adult, these pieces cover a wide spectrum of forms while maintaining his characteristic Russian style.

The Nocturnes, Op. 48 are a set of two nocturnes for solo piano written by Frédéric Chopin in 1841 and published the following year in 1842. They are dedicated to Mlle. Laure Duperré. Chopin later sold the copyright for the nocturnes for 2,000 francs along with several other pieces.

Le festin d'Ésope, Op. 39 No. 12, is a piano étude by Charles-Valentin Alkan. It is the final étude in the set Douze études dans tous les tons mineurs, Op. 39, published in 1857. It is a work of twenty-five variations based on an original theme and is in E minor. The technical skills required in the variations are a summation of the preceding études.

The Prelude in B-Flat Major, Op. 23 No. 2 is a composition by Sergei Rachmaninoff completed and premiered in 1903.

Sergei Prokofiev's Piano Sonata No. 3 in A minor, Op. 28 (1917) is a sonata composed for solo piano, using sketches dating from 1907. Prokofiev gave the première of this in St. Petersburg on 15 April 1918, during a week-long festival of his music sponsored by the Conservatory.

The Études-Tableaux, Op. 33, is the first of two sets of piano études composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff. They were intended to be "picture pieces", essentially "musical evocations of external visual stimuli". But Rachmaninoff did not disclose what inspired each one, stating: "I do not believe in the artist that discloses too much of his images. Let [the listener] paint for themselves what it most suggests." However, he willingly shared sources for a few of these études with the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi when Respighi orchestrated them in 1930.

The Sei pezzi per pianoforte, P 044, is a set of six solo piano pieces written by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi between 1903 and 1905. These salon pieces are eclectic, drawing influence from different musical styles and composers, particularly music of earlier periods. The pieces have various musical forms and were composed separately and later published together between 1905 and 1907 in a set under the same title for editorial reasons; Respighi had not composed them conceiving them as a suite, and therefore did not intend to have uniformity among the pieces. The set, under Bongiovanni, became his first published works. Five of the six pieces are derived from earlier works by Respighi, and only one of them, the "Canone", has an extant manuscript.