Judgment

The British government conceded that there had been an interference with the applicants' right to a private life under article 8 of the European Convention. The issue for the court was therefore whether such an interference could be justified. In order for an interference under article 8 to be justified it is necessary that it is in accordance with the law, in the pursuit of a legitimate aim, and must be considered necessary in a democratic society. The government policy had been given both statutory recognition and recognition by the lower courts and the court considered that the policy could be said to be in the pursuit of the legitimate aim interests of national security" and "the prevention of disorder". However, the court was not satisfied that the policy could be considered "necessary in a democratic society". The court was not satisfied that the government had provided credible justification for its treatment of homosexual personnel. Observing that: [5]

”these attitudes, even if sincerely felt by those who expressed them, ranged from stereotypical expressions of hostility to those of homosexual orientation, to vague expressions of unease about the presence of homosexual colleagues. To the extent that they represent a predisposed bias on the part of a heterosexual majority against a homosexual minority, these negative attitudes cannot, of themselves, be considered by the Court to amount to sufficient justification for the interferences with the applicants' rights outlined above any more than similar negative attitudes towards those of a different race, origin or colour".

The court considered that the government had not offered convincing and weighty reasons for the investigation of the applicants sexual orientation or their subsequent discharge and therefore considered that there had been a breach of their right to a private life under Article 8 of the European Convention. [6]

Mowbray has suggested that the court may have been influenced in its decision by the doubts expressed by some of the Obiter dicta of the domestic proceedings which expressed doubts about the durability of the armed forces policy towards homosexuals.

"Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT) was the official United States policy on military service of non-heterosexual people. Instituted during the Clinton administration, the policy was issued under Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 on December 21, 1993, and was in effect from February 28, 1994, until September 20, 2011. The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted homosexual or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service. This relaxation of legal restrictions on service by gays and lesbians in the armed forces was mandated by Public Law 103–160, which was signed November 30, 1993. The policy prohibited people who "demonstrate a propensity or intent to engage in homosexual acts" from serving in the armed forces of the United States, because their presence "would create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability".

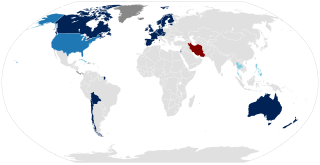

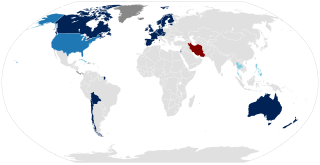

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel are able to serve in the armed forces of some countries around the world: the vast majority of industrialized, Western countries including some South American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile in addition to other countries, such as the United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, Mexico, France, Finland, Denmark and Israel. The rights concerning intersex people are more vague.

Dudgeon v United Kingdom (1981) was a European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case, which held that Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which criminalised male homosexual acts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, breached the defendant's rights under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have developed significantly over time. Today, lesbian, gay and bisexual rights are considered to be advanced by international standards.

X. v. the United Kingdom was a 1978 case before the European Court of Human Rights, challenging the Sexual Offences Act 1956 in the United Kingdom. The case addressed privacy protections and age of consent laws for homosexuals.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Cyprus have evolved in recent years, but LGBTQ people still face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity were decriminalised in 1998, and civil unions which grant several of the rights and benefits of marriage have been legal since December 2015. Conversion therapy was banned in Cyprus in May 2023. However, adoption rights in Cyprus are reserved for heterosexual couples only.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Peru face some legal challenges not experienced by other residents. Same-sex sexual activity among consenting adults is legal. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights provides a right to respect for one's "private and family life, his home and his correspondence", subject to certain restrictions that are "in accordance with law" and "necessary in a democratic society". The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international treaty to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe.

Lustig-Prean and Beckett v United Kingdom (2000) 29 ECHR 548 is a UK labour law and European Convention on Human Rights case on sexual orientation discrimination. The European Court of Human Rights combined judgments for Beckett and Lustig-Prean, and the parallel decisions for Smith and Grady, are regarded as pivotal in gay rights throughout the UK and Europe.

S and Marper v United Kingdom [2008] ECHR 1581 is a case decided by the European Court of Human Rights which held that holding DNA samples of individuals arrested but who are later acquitted or have the charges against them dropped is a violation of the right to privacy under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Canadian military policy with respect to LGBT sexuality has changed in the course of the 20th century from being intolerant and repressive to accepting and supportive.

The United States military formerly excluded gay men, bisexuals, and lesbians from service. In 1993, the United States Congress passed, and President Bill Clinton signed, a law instituting the policy commonly referred to as "Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT), which allowed gay, lesbian, and bisexual people to serve as long as they did not reveal their sexual orientation. Although there were isolated instances in which service personnel were met with limited success through lawsuits, efforts to end the ban on openly gay, lesbian, and bisexual people serving either legislatively or through the courts initially proved unsuccessful.

Alekseyev v. Russia is a case before the European Court of Human Rights concerning the prohibition of the 2006, 2007 and 2008 Moscow Pride gay rights marches in Russia's capital. The case was brought by Russian LGBT activist Nikolay Alexeyev, organiser of the marches, who claimed the banning of the marches had violated Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. He claimed furthermore that he had not received an effective remedy under Article 13 against the violation of Article 11, and that he had been discriminated against by the authorities in Moscow under Article 14 in their consideration of his applications to hold the marches.

Gay and lesbian citizens have been allowed to serve openly in His Majesty's Armed Forces since 2000. The United Kingdom's policy is to allow lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel to serve openly, and discrimination on a sexual orientation basis is forbidden. It is also forbidden for someone to pressure LGBT people to come out. All personnel are subject to the same rules against sexual harassment, regardless of gender or sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation and gender identity in the Australian military are not considered disqualifying matters in the 21st century, with the Australian Defence Force (ADF) allowing LGBT people to serve openly and access the same entitlements as other personnel. The ban on gay and lesbian personnel was lifted by the Keating government in 1992, with a 2000 study finding no discernible negative impacts on troop morale. In 2009, the First Rudd government introduced equal entitlements to military retirement pensions and superannuation for the domestic partners of LGBTI personnel. Since 2010, transgender personnel may serve openly and may undergo gender transition with ADF support while continuing their military service. LGBTI personnel are also supported by the charity DEFGLIS, the Defence Force Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Intersex Information Service.

X and Others v. Austria, Application No. 19010/07, was a human rights case that was decided in 2013 by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The case concerned whether the Government of Austria had discriminated against Austrian citizens who were in same-sex relationships because the wording of the Austrian Civil Code did not permit unmarried same-sex couples access to legally granted second-parent adoptions, whereas it was available to unmarried heterosexual couples.

Not all armed forces have policies explicitly permitting LGBT personnel. Generally speaking, Western European militaries show a greater tendency toward inclusion of LGBT individuals. As of 2022, more than 30 countries allow transgender military personnel to serve openly, such as Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United States. Cuba and Thailand reportedly allowed transgender service in a limited capacity.

Huang v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2007] UKHL 11 is a UK constitutional law case, concerning judicial review.

Craig Jones is a former Royal Navy Officer and LGBT rights defender in the UK armed forces. Jones was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire in the 2006 New Years Honours List for services to Equality and Human Rights in the Armed Forces.

This overview shows the regulations regarding military service of non-heterosexuals around the world.