Aristophanes, son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion, was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete. These provide the most valuable examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy and are used to define it, along with fragments from dozens of lost plays by Aristophanes and his contemporaries.

The Trial of Socrates was held to determine the philosopher's guilt of two charges: asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: "failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges" and "introducing new deities".

A sophist was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics and mathematics. They taught arete, "virtue" or "excellence", predominantly to young statesmen and nobility.

Alcibiades was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently fell from prominence.

Anytus, son of Anthemion of the deme Euonymon, was a politician in Classical Athens. Anytus served as a general in the Peloponnesian War of 431 to 404 BCE, and later became a leading supporter of the democratic forces opposed to the Thirty Tyrants who ruled Athens from 404 to 403 BCE. He is best remembered as one of the prosecutors of the philosopher Socrates in 399 BCE; probably because of that role, Plato depicted Anytus as an interlocutor in the dialogue Meno.

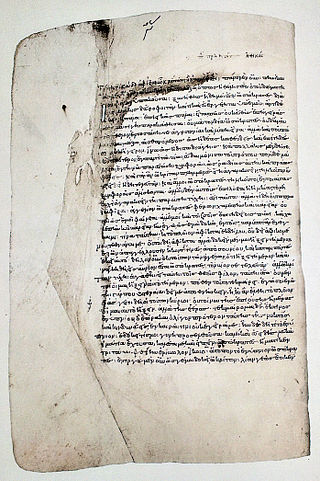

The Clouds is a Greek comedy play written by the playwright Aristophanes. A lampooning of intellectual fashions in classical Athens, it was originally produced at the City Dionysia in 423 BC and was not as well received as the author had hoped, coming last of the three plays competing at the festival that year. It was revised between 420 and 417 BC and was thereafter circulated in manuscript form.

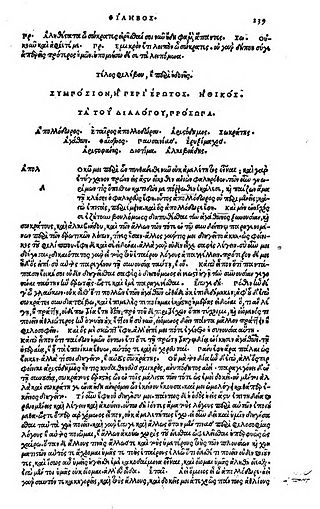

The Symposium is a philosophical text by Plato, dated c. 385–370 BC. It depicts a friendly contest of extemporaneous speeches given by a group of notable men attending a banquet. The men include the philosopher Socrates, the general and political figure Alcibiades, and the comic playwright Aristophanes. The speeches are to be given in praise of Eros, the god of love and desire.

The Birds is a comedy by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It was performed in 414 BC at the City Dionysia in Athens where it won second place. It has been acclaimed by modern critics as a perfectly realized fantasy remarkable for its mimicry of birds and for the gaiety of its songs. Unlike the author's other early plays, it includes no direct mention of the Peloponnesian War and there are few references to Athenian politics, and yet it was staged not long after the commencement of the Sicilian Expedition, an ambitious military campaign that greatly increased Athenian commitment to the war effort. In spite of that, the play has many indirect references to Athenian political and social life. It is the longest of Aristophanes's surviving plays and yet it is a fairly conventional example of Old Comedy.

Crito is a dialogue that was written by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (δικαιοσύνη), injustice (ἀδικία), and the appropriate response to injustice after Socrates's imprisonment, which is chronicled in the Apology.

The Apology of Socrates, written by Plato, is a Socratic dialogue of the speech of legal self-defence which Socrates spoke at his trial for impiety and corruption in 399 BC.

Phædo or Phaedo, also known to ancient readers as On The Soul, is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the Republic and the Symposium. The philosophical subject of the dialogue is the immortality of the soul. It is set in the last hours prior to the death of Socrates, and is Plato's fourth and last dialogue to detail the philosopher's final days, following Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito.

The Apology of Socrates to the Jury, by Xenophon of Athens, is a Socratic dialogue about the legal defence that the philosopher Socrates presented at his trial for the moral corruption of Athenian youth; and for asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens; judged guilty, Socrates was sentenced to death.

Memorabilia is a collection of Socratic dialogues by Xenophon, a student of Socrates. The lengthiest and most famous of Xenophon's Socratic writings, the Memorabilia is essentially an apologia (defense) of Socrates, differing from both Xenophon's Apology of Socrates to the Jury and Plato's Apology mainly in that the Apologies present Socrates as defending himself before the jury, whereas the former presents Xenophon's own defense of Socrates, offering edifying examples of Socrates' conversations and activities along with occasional commentary from Xenophon. Memorabilia was particularly influential in Cynic and later Stoic philosophy.

Chaerephon, of the Athenian deme Sphettus, was an ancient Greek best remembered as a loyal friend and follower of Socrates. He is known only through brief descriptions by classical writers and was "an unusual man by all accounts", though a man of loyal democratic values.

Aeschines of Sphettus or Aeschines Socraticus, son of Lysanias, of the deme Sphettus of Athens, was a philosopher who in his youth was a follower of Socrates. Historians call him Aeschines Socraticus—"the Socratic Aeschines"—to distinguish him from the more historically influential Athenian orator also named Aeschines. His name is sometimes but now rarely written as Aischines or Æschines.

Acropolis Now is a BBC Radio sitcom set in Ancient Greece, written by Lynne Truss. It was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in two series in 2000 and 2002, with subsequent reruns on BBC 7 in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2012. The show follows the fictional adventures of historical Greek characters in Athens: Heraclitus, Aristophanes, Socrates, Plato, Xanthippe, and the Oracle. It is loosely narrated by a chorus, in the convention of Greek dramas.

The prominent Athenian statesman Alcibiades has been criticized by ancient comic writers and appears in several Socratic dialogues. He enjoys an important afterlife, in literature and art, having acquired symbolic status as the personification of ambition and sexual profligacy. He also appears in several significant works of modern literature.

Crito of Alopece was an ancient Athenian agriculturist depicted in the Socratic literature of Plato and Xenophon, where he appears as a faithful and lifelong companion of the philosopher Socrates. Although the later tradition of ancient scholarship attributed philosophical works to Crito, modern scholars do not consider him to have been an active philosopher, but rather a member of Socrates' inner circle through childhood friendship.

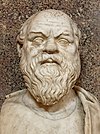

Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no texts and is known mainly through the posthumous accounts of classical writers, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. These accounts are written as dialogues, in which Socrates and his interlocutors examine a subject in the style of question and answer; they gave rise to the Socratic dialogue literary genre. Contradictory accounts of Socrates make a reconstruction of his philosophy nearly impossible, a situation known as the Socratic problem. Socrates was a polarizing figure in Athenian society. In 399 BC, he was accused of impiety and corrupting the youth. After a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced to death. He spent his last day in prison, refusing offers to help him escape.

Socrates is a 1971 Spanish-Italian-French television film directed by Roberto Rossellini. The film is an adaptation of several Plato dialogues, including The Apology, Euthyphro, Crito, and Phaedo.