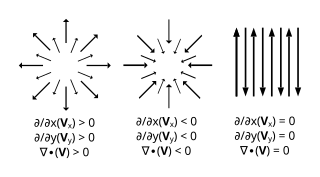

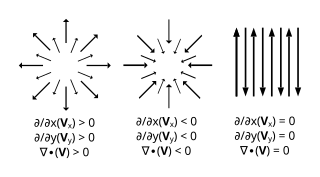

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that operates on a vector field, producing a scalar field giving the quantity of the vector field's source at each point. More technically, the divergence represents the volume density of the outward flux of a vector field from an infinitesimal volume around a given point.

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, and electric circuits. The equations provide a mathematical model for electric, optical, and radio technologies, such as power generation, electric motors, wireless communication, lenses, radar, etc. They describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated by charges, currents, and changes of the fields. The equations are named after the physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell, who, in 1861 and 1862, published an early form of the equations that included the Lorentz force law. Maxwell first used the equations to propose that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon. The modern form of the equations in their most common formulation is credited to Oliver Heaviside.

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport phenomena, flux is a vector quantity, describing the magnitude and direction of the flow of a substance or property. In vector calculus flux is a scalar quantity, defined as the surface integral of the perpendicular component of a vector field over a surface.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

Electric potential is defined as the amount of work energy needed per unit of electric charge to move the charge from a reference point to a specific point in an electric field. More precisely, the electric potential is the energy per unit charge for a test charge that is so small that the disturbance of the field under consideration is negligible. The motion across the field is supposed to proceed with negligible acceleration, so as to avoid the test charge acquiring kinetic energy or producing radiation. By definition, the electric potential at the reference point is zero units. Typically, the reference point is earth or a point at infinity, although any point can be used.

In physics, Gauss's law, also known as Gauss's flux theorem, is a law relating the distribution of electric charge to the resulting electric field. In its integral form, it states that the flux of the electric field out of an arbitrary closed surface is proportional to the electric charge enclosed by the surface, irrespective of how that charge is distributed. Even though the law alone is insufficient to determine the electric field across a surface enclosing any charge distribution, this may be possible in cases where symmetry mandates uniformity of the field. Where no such symmetry exists, Gauss's law can be used in its differential form, which states that the divergence of the electric field is proportional to the local density of charge.

In vector calculus, the divergence theorem, also known as Gauss's theorem or Ostrogradsky's theorem, is a theorem which relates the flux of a vector field through a closed surface to the divergence of the field in the volume enclosed.

Poisson's equation is an elliptic partial differential equation of broad utility in theoretical physics. For example, the solution to Poisson's equation is the potential field caused by a given electric charge or mass density distribution; with the potential field known, one can then calculate electrostatic or gravitational (force) field. It is a generalization of Laplace's equation, which is also frequently seen in physics. The equation is named after French mathematician and physicist Siméon Denis Poisson.

In fluid dynamics, the Euler equations are a set of quasilinear partial differential equations governing adiabatic and inviscid flow. They are named after Leonhard Euler. In particular, they correspond to the Navier–Stokes equations with zero viscosity and zero thermal conductivity.

A continuity equation or transport equation is an equation that describes the transport of some quantity. It is particularly simple and powerful when applied to a conserved quantity, but it can be generalized to apply to any extensive quantity. Since mass, energy, momentum, electric charge and other natural quantities are conserved under their respective appropriate conditions, a variety of physical phenomena may be described using continuity equations.

In vector calculus, a vector potential is a vector field whose curl is a given vector field. This is analogous to a scalar potential, which is a scalar field whose gradient is a given vector field.

In fluid mechanics, or more generally continuum mechanics, incompressible flow refers to a flow in which the material density is constant within a fluid parcel—an infinitesimal volume that moves with the flow velocity. An equivalent statement that implies incompressibility is that the divergence of the flow velocity is zero.

In physics, circulation is the line integral of a vector field around a closed curve. In fluid dynamics, the field is the fluid velocity field. In electrodynamics, it can be the electric or the magnetic field.

In physics and mathematics, in the area of vector calculus, Helmholtz's theorem, also known as the fundamental theorem of vector calculus, states that any sufficiently smooth, rapidly decaying vector field in three dimensions can be resolved into the sum of an irrotational (curl-free) vector field and a solenoidal (divergence-free) vector field; this is known as the Helmholtz decomposition or Helmholtz representation. It is named after Hermann von Helmholtz.

In classical electromagnetism, magnetic vector potential is the vector quantity defined so that its curl is equal to the magnetic field: . Together with the electric potential φ, the magnetic vector potential can be used to specify the electric field E as well. Therefore, many equations of electromagnetism can be written either in terms of the fields E and B, or equivalently in terms of the potentials φ and A. In more advanced theories such as quantum mechanics, most equations use potentials rather than fields.

A flux tube is a generally tube-like (cylindrical) region of space containing a magnetic field, B, such that the cylindrical sides of the tube are everywhere parallel to the magnetic field lines. It is a graphical visual aid for visualizing a magnetic field. Since no magnetic flux passes through the sides of the tube, the flux through any cross section of the tube is equal, and the flux entering the tube at one end is equal to the flux leaving the tube at the other. Both the cross-sectional area of the tube and the magnetic field strength may vary along the length of the tube, but the magnetic flux inside is always constant.

In physics, Gauss's law for magnetism is one of the four Maxwell's equations that underlie classical electrodynamics. It states that the magnetic field B has divergence equal to zero, in other words, that it is a solenoidal vector field. It is equivalent to the statement that magnetic monopoles do not exist. Rather than "magnetic charges", the basic entity for magnetism is the magnetic dipole.

In physics, Gauss's law for gravity, also known as Gauss's flux theorem for gravity, is a law of physics that is equivalent to Newton's law of universal gravitation. It is named after Carl Friedrich Gauss. It states that the flux of the gravitational field over any closed surface is proportional to the mass enclosed. Gauss's law for gravity is often more convenient to work from than Newton's law.

In fluid dynamics, The projection method is an effective means of numerically solving time-dependent incompressible fluid-flow problems. It was originally introduced by Alexandre Chorin in 1967 as an efficient means of solving the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. The key advantage of the projection method is that the computations of the velocity and the pressure fields are decoupled.

In ideal magnetohydrodynamics, Alfvén's theorem, or the frozen-in flux theorem, states that electrically conducting fluids and embedded magnetic fields are constrained to move together in the limit of large magnetic Reynolds numbers. It is named after Hannes Alfvén, who put the idea forward in 1943.