In vector calculus, the curl, also known as rotor, is a vector operator that describes the infinitesimal circulation of a vector field in three-dimensional Euclidean space. The curl at a point in the field is represented by a vector whose length and direction denote the magnitude and axis of the maximum circulation. The curl of a field is formally defined as the circulation density at each point of the field.

In mathematics, an operator is generally a mapping or function that acts on elements of a space to produce elements of another space. There is no general definition of an operator, but the term is often used in place of function when the domain is a set of functions or other structured objects. Also, the domain of an operator is often difficult to characterize explicitly, and may be extended so as to act on related objects.

In vector calculus and differential geometry the generalized Stokes theorem, also called the Stokes–Cartan theorem, is a statement about the integration of differential forms on manifolds, which both simplifies and generalizes several theorems from vector calculus. In particular, the fundamental theorem of calculus is the special case where the manifold is a line segment, Green’s theorem and Stokes' theorem are the cases of a surface in or and the divergence theorem is the case of a volume in Hence, the theorem is sometimes referred to as the fundamental theorem of multivariate calculus.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

In physics, specifically electromagnetism, the Biot–Savart law is an equation describing the magnetic field generated by a constant electric current. It relates the magnetic field to the magnitude, direction, length, and proximity of the electric current.

In vector calculus, the divergence theorem, also known as Gauss's theorem or Ostrogradsky's theorem, is a theorem relating the flux of a vector field through a closed surface to the divergence of the field in the volume enclosed.

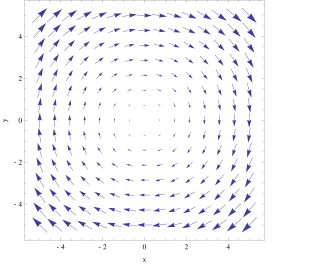

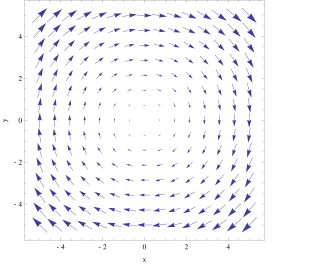

In continuum mechanics, vorticity is a pseudovector field that describes the local spinning motion of a continuum near some point, as would be seen by an observer located at that point and traveling along with the flow. It is an important quantity in the dynamical theory of fluids and provides a convenient framework for understanding a variety of complex flow phenomena, such as the formation and motion of vortex rings.

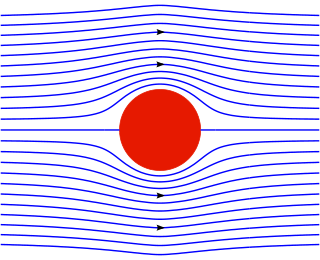

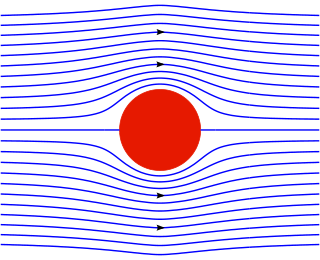

In fluid dynamics, Stokes' law is an empirical law for the frictional force – also called drag force – exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers in a viscous fluid. It was derived by George Gabriel Stokes in 1851 by solving the Stokes flow limit for small Reynolds numbers of the Navier–Stokes equations.

In fluid dynamics, two types of stream function are defined:

In vector calculus, a conservative vector field is a vector field that is the gradient of some function. A conservative vector field has the property that its line integral is path independent; the choice of path between two points does not change the value of the line integral. Path independence of the line integral is equivalent to the vector field under the line integral being conservative. A conservative vector field is also irrotational; in three dimensions, this means that it has vanishing curl. An irrotational vector field is necessarily conservative provided that the domain is simply connected.

In mathematical physics, scalar potential describes the situation where the difference in the potential energies of an object in two different positions depends only on the positions, not upon the path taken by the object in traveling from one position to the other. It is a scalar field in three-space: a directionless value (scalar) that depends only on its location. A familiar example is potential energy due to gravity.

In physics and mathematics, the Helmholtz decomposition theorem or the fundamental theorem of vector calculus states that certain differentiable vector fields can be resolved into the sum of an irrotational (curl-free) vector field and a solenoidal (divergence-free) vector field. In physics, often only the decomposition of sufficiently smooth, rapidly decaying vector fields in three dimensions is discussed. It is named after Hermann von Helmholtz.

In classical electromagnetism, magnetic vector potential is the vector quantity defined so that its curl is equal to the magnetic field: . Together with the electric potential φ, the magnetic vector potential can be used to specify the electric field E as well. Therefore, many equations of electromagnetism can be written either in terms of the fields E and B, or equivalently in terms of the potentials φ and A. In more advanced theories such as quantum mechanics, most equations use potentials rather than fields.

The electric-field integral equation is a relationship that allows the calculation of an electric field generated by an electric current distribution.

The following are important identities involving derivatives and integrals in vector calculus.

The gradient theorem, also known as the fundamental theorem of calculus for line integrals, says that a line integral through a gradient field can be evaluated by evaluating the original scalar field at the endpoints of the curve. The theorem is a generalization of the second fundamental theorem of calculus to any curve in a plane or space rather than just the real line.

The Navier–Stokes existence and smoothness problem concerns the mathematical properties of solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations, a system of partial differential equations that describe the motion of a fluid in space. Solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations are used in many practical applications. However, theoretical understanding of the solutions to these equations is incomplete. In particular, solutions of the Navier–Stokes equations often include turbulence, which remains one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics, despite its immense importance in science and engineering.

In mathematics, vector spherical harmonics (VSH) are an extension of the scalar spherical harmonics for use with vector fields. The components of the VSH are complex-valued functions expressed in the spherical coordinate basis vectors.

Stokes' theorem, also known as the Kelvin–Stokes theorem after Lord Kelvin and George Stokes, the fundamental theorem for curls or simply the curl theorem, is a theorem in vector calculus on . Given a vector field, the theorem relates the integral of the curl of the vector field over some surface, to the line integral of the vector field around the boundary of the surface. The classical theorem of Stokes can be stated in one sentence:

Multipole radiation is a theoretical framework for the description of electromagnetic or gravitational radiation from time-dependent distributions of distant sources. These tools are applied to physical phenomena which occur at a variety of length scales - from gravitational waves due to galaxy collisions to gamma radiation resulting from nuclear decay. Multipole radiation is analyzed using similar multipole expansion techniques that describe fields from static sources, however there are important differences in the details of the analysis because multipole radiation fields behave quite differently from static fields. This article is primarily concerned with electromagnetic multipole radiation, although the treatment of gravitational waves is similar.